Let’s think about the films released in 1946. From the Europeans there was De Sica’s Shoeshine; Rossellini’s Paisan and La Belle et la Bête by Cocteau. There were two masterworks of British cinema, A Matter of Life and Death, directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, and Great Expectations, directed by David Lean.

The American films I love from that year include the melodramas The Razor’s Edge and A Stolen Life. Then there are John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, Hitchcock’s Notorious, Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, the indescribable The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks), Robert Siodmark’s The Killers – the film that makes you come to understand why Ava Gardner became Ava Gardner – the list goes on and on.

I’m often asked why Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, also released in 1946, wasn’t that big a deal at the time. Maybe we can make a comparison between Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon and Nolan’s Oscar-laden Oppenheimer.

The latter is the film that we need now. The former is the film that will live.

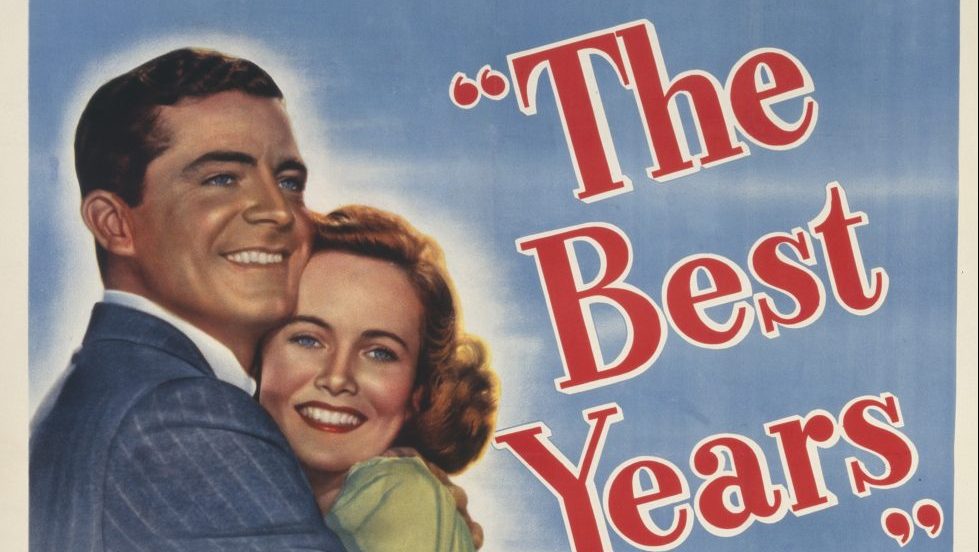

The picture that was the biggest movie of 1946 was The Best Years of Our Lives. The director was the great William Wyler, who knew everything about movies and why people came to see them. The cinematographer was Gregg Toland, whose other credits include Welles’s Citizen Kane, Wyler’s Wuthering Heights – for which Toland won an Oscar – and John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath.

The picture is about three GIs returning home; a banker turned sergeant in the Pacific theatre, played by Fredric March, who won best actor; a flight commander who fought in the European theatre, played by the deeply underrated Dana Andrews, and a disabled sailor played by Harold Russell, who not only won the Oscar for best supporting actor but also took home a special Oscar for his work highlighting the realities of life for disabled military personnel.

The Best Years of Our Lives is a picture about coming home from war, and readjusting to the home front. It was quite simply what was happening in 1946. And that is one of the secrets of a sweep; of a picture that carries all before it.

My feeling is that we sense a new nuclear age. That The Bomb is coming back and we need to know more about how it came to be. But we will also need to know how the world that we live in now came to be, and Flowers will emerge as the stronger of the big, serious movies from now.

Toland’s lighting for deep focus, his camera, enabled you to see all the way back – everything around the moment. So that you were in the shot, too.

At the end of The Best Years of Our Lives, Dana Andrews, the airman vet, crosses a crowded room to kiss Teresa Wright’s character, the woman he loves. Toland lights Wright from above, in front of our eyes, and we see his technique. His eye. His empathy.

His most memorable shot for me, though, is one involving an African American porter. A real person.

In the scene, a rich man is buying his way on to a flight home, while the GIs in the background, languishing on couches and chairs, have to wait for a free flight.

The rich man ostentatiously buys a ticket and then orders the porter to fetch his bags and follow him.

For a second, the porter, obviously a real porter roped into the scene, glances straight at the camera.

In doing so, he walks out of the movie for a second to give us the face of what a real porter was going through, what a black man in those days had to endure at the hands of a white man, even while black GIs are waiting in the background to fly home.

That moment would have had to be signed off by Wyler, the director.

He did. But Toland caught it.

He did not wipe it; nor did he call for the scene to be done over. That tells you everything about this immortal cinematographer.