Something long overdue is happening in the Netherlands. After decades of denial, during which pride in its explorers and conquerors has trumped regret at what was done to indigenous people, the country is beginning to grapple with its colonial past.

The reckoning began with Black Lives Matter and the Dutch role in the slave trade, but has now moved on to what was once the Netherlands’ prize colonial possession, the vast Indonesian archipelago, which it dominated for more than three centuries.

It was as recently as 2006 that a Dutch prime minister praised the can-do mentality of the Dutch East India Company that colonised and exploited Indonesia. But now the Netherlands is prepared to face up to what the prime minister, Mark Rutte, last month called the “shameful facts” of systematic atrocities committed by Dutch troops in its last, bloody, colonial campaign, the attempt between 1945 and 1950 to quell Indonesian independence.

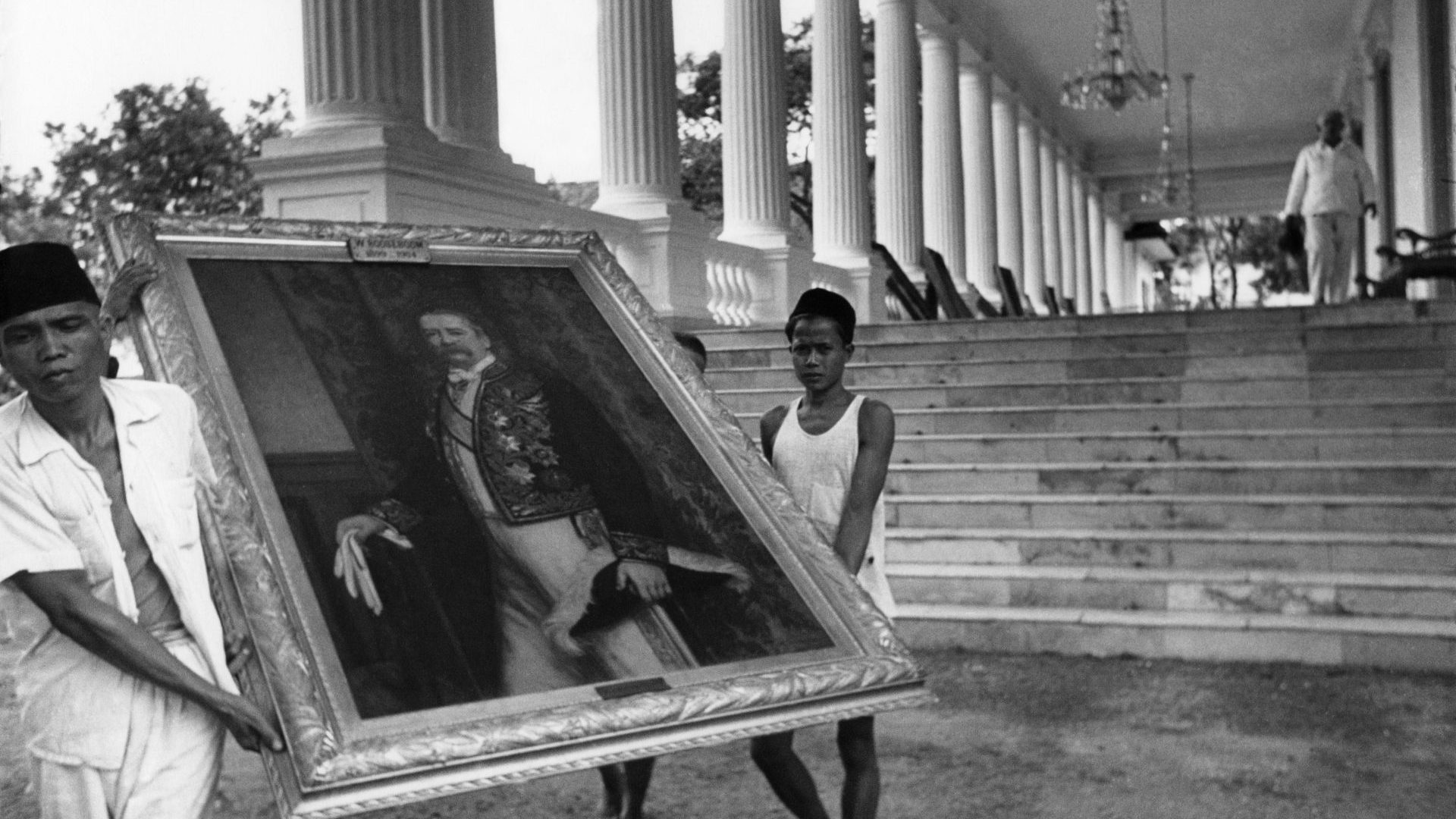

Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum is known mainly for its Rembrandts and other masters of the Dutch Golden Age, an economic and cultural flowering in the 17th century partly funded by colonialism. It is now showing an exhibition on Indonesia’s independence struggle, called Revolusi!

At the Rijksmuseum, room after room is filled with personal stories, mostly of Indonesians who lived through the Independence war, yet there’s precious little that links to the centuries of exploitation and massacres that went before. And for a brutal war of independence, the imagery is remarkably sanitised.

Rutte’s apology for the Dutch atrocities seems similarly stuck in a vacuum. As with the inquiry that precipitated it, he avoided the use of the words “war crimes”. And he quickly shut down talk of additional compensation for Indonesians beyond very limited existing arrangements that were forced on the government by court cases brought by survivors and descendants in recent decades.

Jeffry Pondaag, an Indonesian living in the Netherlands, initiated some of those lawsuits through his foundation, the Dutch Debts of Honour Committee. He is scathing about Rutte’s apology and the inquiry that led to it.

“It’s a put-up job,” he says. “The king already apologised for extreme violence. Now the inquiry uses that term again but not war crimes.” He suspects that the researchers, who were funded by the government, had been asked to avoid the term in order to make the results more politically palatable. They deny this and have said they now regret not having mentioned the term at least in their introduction.

Rutte and his centre-right Liberal VVD party have long refrained from harsh criticism of past Dutch behaviour in Indonesia with an eye on veterans and their descendants and on its own nationalist flank. Two far-right parties with a significant presence in parliament immediately condemned the inquiry and Rutte’s apology.

“Falsification of history,” tweeted the PVV’s Geert Wilders, while Thierry Baudet of the rival FvD went a step further and waxed nostalgically about how much better off Indonesia was under the Dutch. “What a loss, what a loss. White Man’s Burden,” he tweeted.

Despite the political ructions, Gert Oostindie, one of the lead researchers on the project that detailed the Dutch use of “extreme violence” in its former colony, sees progress in Rutte’s acknowledgement. “This used to be very much a left-right issue in politics, which is a pity because it is all about our Vergangenheitsbewältigung.” Significantly, he is using German postsecond world war term for grappling with a dark past.

The research that led to Rutte’s apology also focuses on the overarching responsibility of the Dutch government, military and judiciary at the time. Having lost its large and lucrative colony to the Japanese in 1942, the Dutch, against the advice of their American and eventually also British allies, decided to re-establish their authority after the end of WWII, despite Indonesia having declared independence in 1945.

An initial outburst of violence from the Indonesian side killed thousands of Europeans, Indo-Europeans and real or perceived Indonesian allies of the Dutch. The subsequent war killed an estimated 100,000 Indonesians. Around 5,000 Dutch troops died, many of them not in combat.

As late as 2012, when three national institutes – the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV), the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (NIOD), and the Netherlands Institute for Military History (NIMH) – proposed a thorough inquiry, the government declined. It only got on board in 2016.

Oostindie, who until recently headed the KITLV, says that the Dutch attitude towards the colonial era has shifted significantly over the past two decades. “First towards slavery and more recently towards this subject. It’s significant that it can be discussed at all and with a much more critical discourse.”

The Netherlands is the one northwestern European nation that might rival, if not surpass, the UK in nostalgia for its colonies. A 2020 YouGov survey found that 50% of the Dutch were still proud of their colonial past vs 32% in the UK. But Oostindie points to a Dutch poll a year later that had just 35% express pride.

Pondaag and others point out that Rutte’s apology does not include the previous colonial period and mindset, in which, they say, the 1945-1950 violence is anchored. Not surprisingly, critics on the other side of the divide, those who speak for the veterans and their families, say that the inquiry focuses too much on violence from the Dutch side.

The large group of Indo-Dutch people now in the Netherlands who in some way trace a connection to the former colony is diverse and runs from former colonialists to mixed Indo-Europeans to Indonesian allies of the Dutch, including a large group of Moluccans who fought for the colonial army. Especially among veterans and their families, the research was awaited with some trepidation.

“I’ve talked to patients who were very concerned, especially children who were worried that a parent would be depicted as a war criminal,” says Inez Schelfhout of ARQ Centrum’45, the Dutch treatment and expertise centre for psycho-trauma. After Rutte’s apology, she hopes for a more open debate without anybody being excluded. “That is extremely important for processing the past. I think that went wrong in the 1950s, sixties, seventies, when a lot was being kept silent.”

The Indo-Dutch community was long known for the “great silence”, confirm others who know it. “It was something that was not talked about, it was suppressed,” says Rocky Tuhuteru, director of Pelita, the care organisation for the Indo-Dutch, who is himself of Moluccan descent. “But it is a period of history that very much influences our identity, also mine, and that of our children and grandchildren.” Part of that identity was also formed by the widespread racism that the newcomers encountered when they arrived in the 1950s, and which long persisted. Tuhuteru says that neither society nor the government were ready to deal with what had happened. “Until today we talk about the unresolved colonial past. The Dutch state, in my opinion, handled it in an abject manner.”

He welcomes the prime minister’s call for a public debate because it represents a break with the past. “That’s why this is a historic statement by Rutte, because he clearly distances himself from his predecessors.”

In Indonesia, many are still sceptical. Ady Setyawan founded a historical society in the city of Surabaya, on Java. He is not impressed by Rutte’s apologies. “As someone who has focused on this period, I say sorry is not enough. When you hit someone’s car, you don’t just say sorry, you also pay for the damage.”

It’s not difficult to find out what happened, he says. “When you come to Java, you can find lots of monuments where they burned or bombed a whole village.”

Ferry Biedermann is a journalist based in Amsterdam writing on Europe, the Netherlands and Brexit. He’s a former correspondent in the Middle East for, among others, the Financial Times