Private individuals are to thank for many of the world’s great public art collections, and Vienna is no exception. The Kunsthistorisches Museum, the jewel in the city’s Museums Quarter, was built to house the vast collections of the Habsburgs, Austria’s ruling dynasty for more than 600 years. Nearby, the Leopold Museum is a memorial in perpetuity to the efforts of two ordinary citizens, the ophthamologists Rudolf and Elisabeth Leopold, who in the 1950s established one of the world’s great collections of Austrian art. Its peerless holdings of Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt were gifted to the public via a state-funded museum that opened in 2001.

The Heidi Horten Collection, which opened days before the death of its founder on June 12, is the latest addition to the city’s cultural landscape. Situated between the State Opera and the Albertina – itself named after Duke Albert Casimir of Sachsen-Teschen, whose collection it contains – the gallery occupies a newly refurbished building, familiar to many Viennese in its previous incarnation as a box office, selling tickets for the State Opera.

As just another iteration of the city’s ubiquitous baroque architecture, the

building’s shell seems conventional enough. But behind a screen of greenery, large modern windows reveal an interior transformed by the Viennese architects The Next Enterprise into minimal, wide-open spaces.

As such, the building is a neat metaphor for the museum itself, which, though it appears at first to fit easily into the city’s cultural scene, is markedly different to its established institutions.

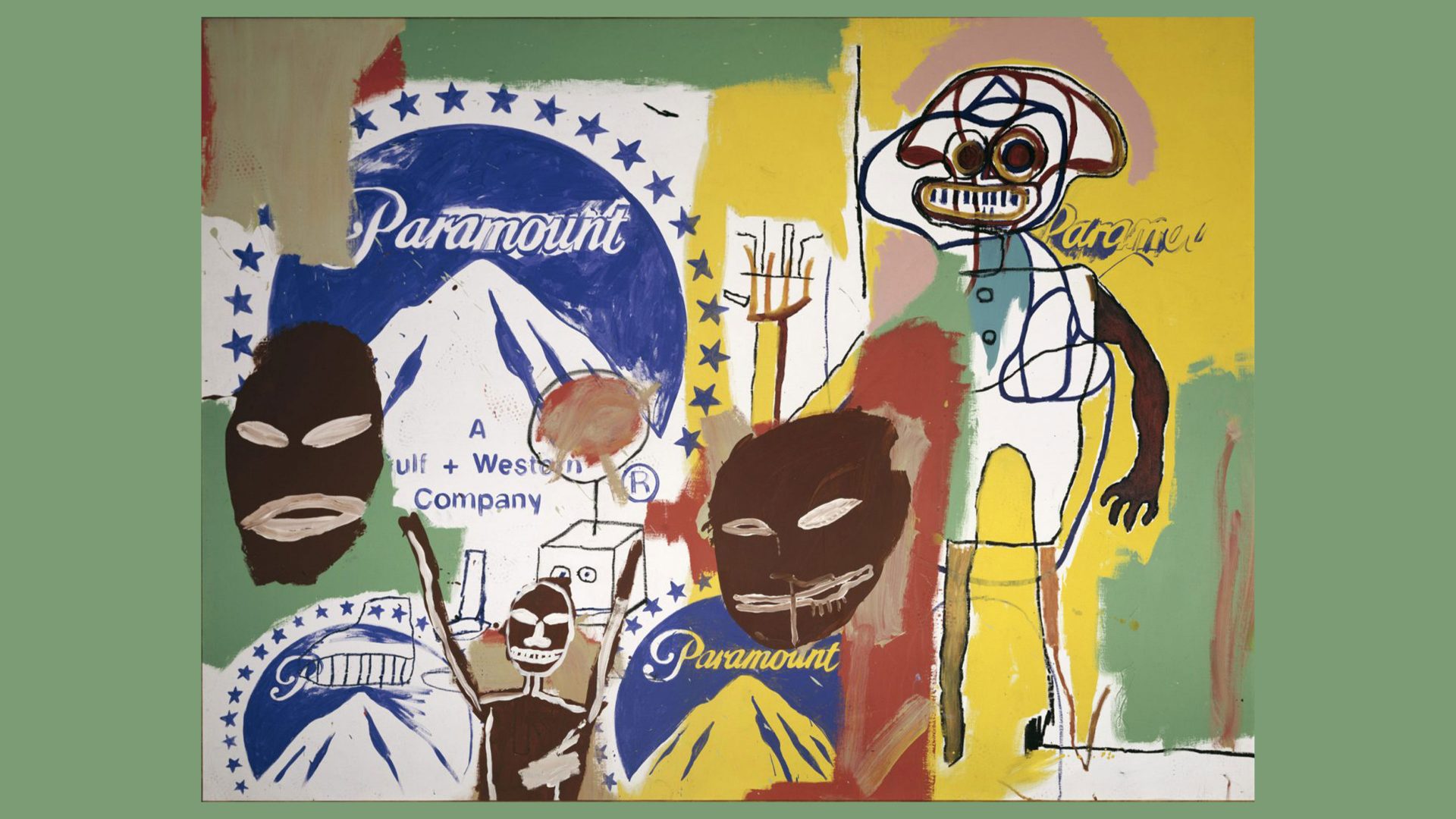

Unlike almost every other art museum in Vienna, the collection has not been gifted to the state, and remains instead in private ownership, a situation that is unaffected by the recent death of its founder. Entirely self-funded, and with a standard admission charge of €15 (£12.75), the collection of works by 20th-century artists such as Francis Bacon and Marc Chagall, and contemporary artists including Damien Hirst and Marc Quinn, is representative of a new global trend for private museums. Its purpose, according to the collection’s website, “is to ensure the ongoing preservation and permanent presentation of the art collection of Heidi Goëss-Horten.”

Private museums have existed since the 19th century, with Sir John Soane’s Museum in London and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston among the best-known examples, but their numbers have exploded in the

last 20 years. In her 2021 book The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum,

journalist and art market expert Georgina Adam cites a 2016 report compiled by the website Larry’s List, which numbers private museums at 317 worldwide. Of these, she writes, “a stunning 70% were founded after the year 2000; even more startlingly, nearly one-fifth of these private spaces were built during the last five years.”

The reasons are varied and, crudely stated, range from a genuine desire to

contribute to society, to personal vanity, to optimising tax arrangements – or a combination of all three. Still, in Vienna, where culture is unambiguously the domain of the state, the addition of a private museum to the city’s cultural offering is especially noteworthy.

In fact, Horten decided only recently to establish the museum, following a

successful exhibition of highlights from the collection at the Leopold Museum in 2018. Afterwards, Horten said: “Due to the enormously positive

resonance and great interest of exhibition visitors after the first public presentation in 2018, I sensed this was the right way. Originating in this tremendous response, a wish took shape inside me to make my collection

accessible and preserve it for future generations. Thus, the decision was

made to found a museum of my own.”

The inaugural exhibition, titled Open, which runs through the summer, includes around 30 pieces from the 700 or so in the collection, and has been devised to show off the new building as much as the art. Two floating platforms create three floors in total, the long sightlines that extend between floors and rooms adding to the overall sense of open space. More intimate galleries with traditional parquet floors radiate from the central spaces, and temporary walls can be installed should a bigger, more complex exhibition require it.

For now, the focus is on giving a flavour of the collection and the character of the woman behind it. Born in Vienna in 1941, Horten began buying art in the 1970s with her first husband, Helmut Horten, acquiring works by established figures such as Picasso, Chagall and Emil Nolde.

She began collecting seriously after her husband’s death in 1987, and from

the mid-1990s enlisted the help of the art historian Agnes Husslein-Arco, at

the time the managing director of Sotheby’s Austria, and now the director of the Heidi Horten Collection. Under Husslein-Arco’s guidance, the collection became more adventurous, broadening out to include abstract and contemporary art, and works by less well-known artists including the French-American sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle.

Even so, Horten’s personal taste remained her guiding principle. “I’m a

visual person,” she said. “When I see an artwork, I know instantaneously

whether it is worth considering for my collection. From these acquisitions

made based on a gut feeling, there eventually developed an extensive

collection that in any case reflects my personal taste.”

As a result, the current exhibition is particularly strong on bright colours

and animals, two passions that combine eye-catchingly in Lena Henke’s enormous purple pig, Ur-Mutter, 2019.

Though Horten was not interested in setting quotas for artists according to

gender, age or ethnicity, Husslein-Arco says that female artists are reasonably well represented. Though sadly none are women, special commissions for the new building highlight Horten’s interest in supporting Austrian artists, while studio space, and provision for schoolchildren, indicate her wish to engage and support the next generation of artists and audiences.

Horten belongs to a tradition of female collectors and benefactors from Peggy Guggenheim, whose museum in Venice is a leading collection of 20th-century art, to Maja Hoffmann, the Swiss collector who last year opened a “creative campus” in Arles, in the south of France.

Husslein-Arco writes that the museum “rivals the holdings of leading museums in quality, boasting treasures that are unmatched in Vienna, in Austria, even in Europe.” The collection’s outstanding quality means that it could have been donated to public museums, where it would have plugged gaps in existing collections, and arguably performed a more meaningful public service.

Making a private collection public is a decision that brings with it considerable scrutiny, especially in Vienna, a city scarred by its Nazi past.

Helmut Horten, Heidi Horten’s first husband and the source of the money

that financed the collection, made much of his fortune from department

stores acquired from Jewish owners who had had their property confiscated by the Third Reich. A report commissioned by the Horten Collection from the historian Peter Hoeres of the University of Würzburg, was completed in January this year, having been tasked with an examination of “Helmut Horten’s accumulation of assets from 1936 to 1945.” Among its conclusions, the report stated that Horten “benefitted from the economic circumstances provided by the Nazi state. He did not, however, take active steps to exert pressure on the Jewish sellers.”

Due diligence of this sort is a necessary feature of art ownership today, but in making her collection public, Heidi Horten inevitably invited even greater scrutiny of her affairs.

In a book published to mark the museum’s opening, Husslein-Arco hints at motivations beyond pure beneficence, writing that private museums in Europe have “been fuelled by the decline of an alternative form of endowment, the permanent loan to a public institution, which has turned out to be fraught with complications.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by British curator Jasper Sharp, the founder of Phileas: A Fund for Contemporary Art in Vienna. He argues that the Austrian

tax system fails to incentivise donations to museums, saying: “As someone who is obsessed with the notion of public museums, I always ask myself, ‘Is there some failure on the part of public institutions that so many people in recent years have been opening private museums, and if so, what can be done to address that?’”.

But while the collection undoubtedly represents a loss to the state sector, it may signal a new dimension to the city’s art scene, which has never recovered from the loss of so many art dealers in the 1930s, many of whom were Jews persecuted under the Nazi regime. Elisabeth Thoman, co-founder of Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman, has been working with Austrian contemporary artists for over 40 years but she says: “The possibilities in the

art market for Austrian galleries and artists are really very, very limited. “We need international collectors.”

Whether or not the Heidi Horten Collection signals a developing entrepreneurial spirit alongside the Viennese cultural behemoth remains

to be seen, and Husslein-Arco writes rather cryptically that the museum “is

not about the widely criticised entanglement of art and the market”. Instead, she says, “its objective is to safeguard the individual collector’s ideas and wishes, the vision that shaped the development of the collection”. But given Horten’s commitment to fostering future generations of artists, it may be that a shift in emphasis offers a welcome shot in the arm for the city’s art scene.

The Heidi Horten Collection, Hanischgasse 3, 1010, Wien; www.hortencollection.com, until October 2

Florence Hallett is a freelance art writer and critic