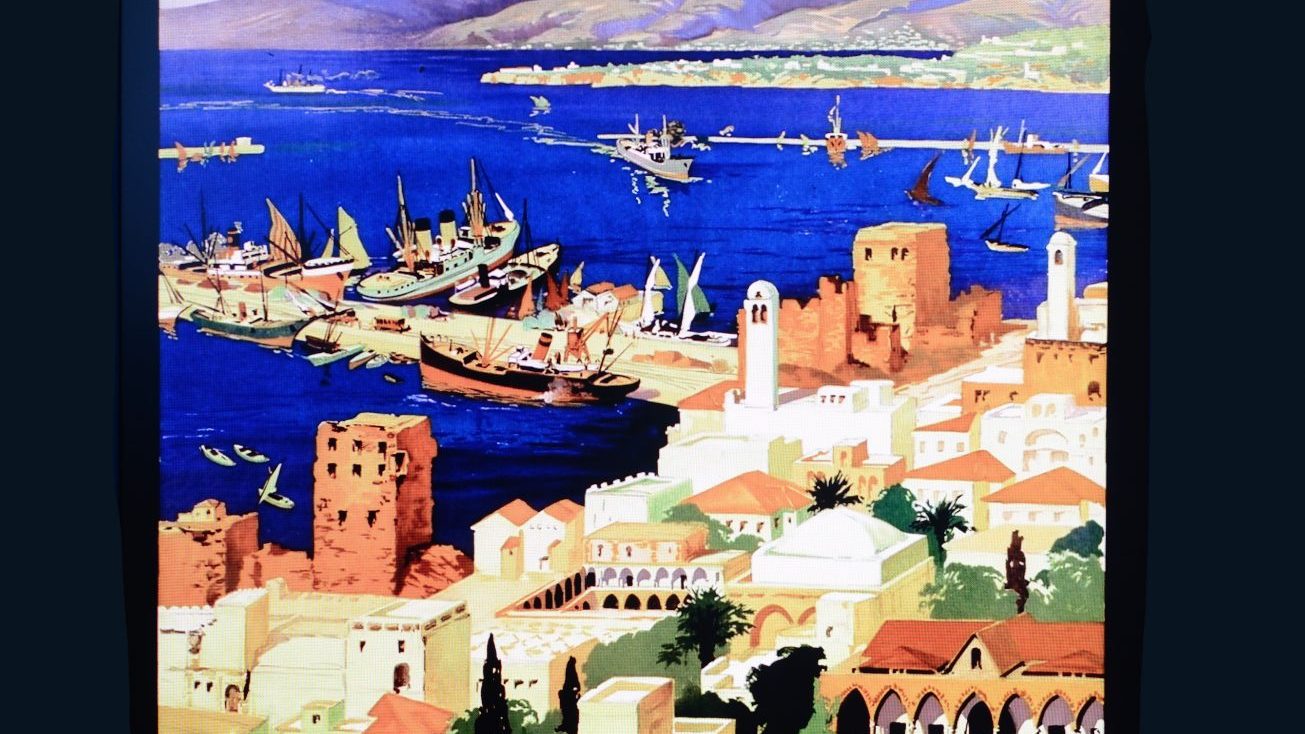

Hard to imagine but Beirut, that most broken of cities, was once considered the Paris of the Middle East, a magnet for a glamorous fusion of actors, artists and spies. A world of flash American cars cruising along the corniche, nightclubs, and chic hotels like the Saint Georges where Brigitte Bardot, Peter O’Toole, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, not to mention notorious double agent Kim Philby, drank cocktails and lazed in the sun.

It was a brief, ostensibly settled time between 1958, when riots against the incumbent president were quelled by an invasion of US troops, and 1975, when civil war broke out once again and blighted the country for 15 years.

The city was bursting at the seams with intellectuals, artists, writers and

designers, many of whom travelled to seek inspiration from the artistic

milieus of Paris, New York and London, Mexico and São Paulo. They not only absorbed the lessons learnt in many a European art gallery or artist’s

studio, but also tried to create a sense of post-colonial identity by looking to

the country’s culture of Islamic art, icons, architecture and calligraphy.

This brief flowering of creativity is celebrated – and questioned – in Beirut

and The Golden Sixties: A Manifesto of Fragility at the Gropius Bau gallery in

Berlin, featuring more than 230 works by 34 artists who flourished in the

1960s and 70s, many of whom are still working today.

The keyword is fragility. Even during this “golden age” rivalry raged between the ruling parties, creating a permanent sense of dysfunction; easy-going banking laws encouraged corruption – making some very rich and others very poor; while the seeds of strife were sown when the Palestine Liberation Front were pushed out of Jordan in 1970 and settled in Lebanon, where they continued their fight against Israel.

Today, after years of uncertainty – continued internecine strife, assassinations, invasions by foreign powers – Lebanon is still in the throes of economic and social crisis, the gap between rich and poor continues to widen and, as if matters could not be any worse, in 2020 a warehouse of ammonium nitrate exploded, destroying the port of Beirut, leaving an estimated 300,000 people homeless and killing more than 210 people. The people blamed the corruption and incompetence of the government for their neglect of the store.

Sam Bardaouil, who curated the exhibition with Till Fellrath, says: “Usually when people go through these extreme situations such as we are experiencing today there is a tendency to look back in time and romanticise a previous era as being a way better time than the present. While this can be very soothing and lead to a sense of belonging, everybody subscribes to a certain narrative or an ideal of what that place is and what that place can pretend to be.

“It can also be very, very misleading because we start missing all the blemishes in the golden picture that we portray of that time and not realise that, perhaps, a lot of the problems that we are going through now have their roots in that particular moment.

“If it was such a great time in the 60s why did we end up having a war only a few years later?”

The aim of the exhibition is to show that the art scene of those years was a

microcosm of a community which on one hand was extremely cosmopolitan

and on the other extremely radicalised, but also reflected the political camps and warring parties which were grasping for power.

The visitor to the exhibition is greeted with a photograph of the US landing in 1958 juxtaposed with a painting of the scene by Khalil Zgaib, a pioneer of modern Lebanese art, who captured, in his typically detailed style, onlookers gathering on the beach to witness a moment which was both dangerous and farcical. The party spirit was enhanced by enterprising

local vendors turning out to sell cigarettes, cold drinks and sandwiches for the American soldiers.

The show tackles the early manifestations of feminism with the seductive imagery of entwined bodies by Cici Sursock in Corps et mes (Bodies

and Souls). Critics hailed her audacity and noted that she painted like a man,

which may not have been quite the compliment she wanted or deserved.

Huguette Calland, (1931-2019), whose work was shown at Tate St Ives in 2019, took a radical view of the body and sexuality with erotic, semi-abstract figures, while Juliana Seraphim, a Palestinian refugee, painted sensual, fantastical women, inspired by the frescoes of winged beings on the ceiling of her grandfather’s home in Jerusalem, a former convent.

Few capture the soul of the country more movingly than Etel Adnan (1925-

2021) whose bold abstracts and landscapes are inspired by the colours of Beirut and the Lebanese countryside.

No collection of that era would be complete without work by Saloua Raouda Choucair, the grande dame of the Lebanese art world, who died in 2017, and whose sculptures and paintings combined lessons she imbibed working alongside the abstract artist Fernand Léger in Paris with her own unique interpretation of the principles of Islamic art with which she had grown up.

There are the bold geometric shapes by Aref El Rayess (1928-2005), passionate abstracts by Shafic Abboud (1926-2004) and bright, bold, paintings by Rafic Charaf who was inspired by the region’s oral history and folklore and created a series in 1971 depicting the pre-Islamic Arab knight Antar, famous for both his poetry and adventurous life.

The exhibition inevitably covers the end of the era when the dark clouds of

civil strife were gathering. Jamil Molaeb’s Civil War Diary depicts harrowing scenes of fear and cruelty such as a massacre of passengers on a bus, while Nicolas Moufarrege (1947-1985) created the powerful embroidery Le sang du phénix (The Blood of the Phoenix). A pair of enormous disembodied eyes hover among towering columns, a Lebanese cedar stands to one side, the ground is covered in a river of blood.

Badaouil argues that the show is reflecting repercussions of the civil war that are still evident – the discord, the schisms and the daily tragedies – and emphasises the contradictions between the so-called Golden Age and the fact that today conditions in the country are far from utopian.

“We are trying to make sense of the situation and find out how the work of the artists can be relevant. What does it mean to make art, culture, films,

installations and performance in a time of crisis? It can be paralysing and it can be very regenerative. It can trigger new departures and new openings.”

Husband-and-wife photographers Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige are doing just that – exposing the ruptures in their society by looking to the past for lessons for today.

For their contribution to the current round of the Prix Pictet, the photography prize worth 100,000 Swiss francs (£82,000) to the winner, they

made a work entitled Wonder Beirut in which they acquired postcards from

the “golden age” that proudly depicted apartment blocks and smart hotels but exposed what was happening beneath the gilded exteriors by superimposing images of bomb blasts and bullet holes that were fired during the civil war at those very buildings.

They have personal, painful experience of the dystopia that grips the city. When the blast went off in 2020, Hadjithomas was in a cafe and thrown to the ground by the force of the explosion, and her back peppered with shards of glass. Joreige, who had planned to work late at their studio, which overlooks the port, had been persuaded instead to play tennis with his children in the mountains. The studio was wrecked.

The couple are presenting an installation – they call it an activation – a mix of video and poetry at the Golden Age show that is a reaction to both the 60s and 70s and to the current crisis. They visited the historic Sursock Museum in Beirut, which had been badly damaged in the blast, and used CCTV from the museum to record the dust from the blast – “so dense it was like creating ghosts” – and used the videos to make a further 12 screens, which track in synch from room to room, filming the paintings that still hung on the walls.

Some of the very same works can also be seen in the exhibition bringing, as they say, the past to the present and also serving as a message that the Lebanese art world remains resilient, still finding ways to express itself.

Rachel Dedman of the Victoria and Albert Museum until 2019, who curated the 2021 Jameel prize, an award for contemporary art inspired by Islamic tradition, lived in Beirut for six years and witnessed the constant interchange of ideas and shared projects in the city with exhibitions, talks, interventions and protest.

One activist, Jameel finalist Farah Fayyad, a graphic designer and printmaker whose ambition is to rejuvenate the use of Arabic script, installed a screen-printing press in the city centre with a group of friends using Arabic typography for slogans on T-shirts such as Revolution or From Tyranny Blossoms Disobedience.

It was a spontaneous reaction to the political fallout from the blast, a small gesture perhaps, but typical of a society yearning for an age, if not golden, at least untarnished by violence and corruption. One without the constant imperative to react to a nation’s pain.

It is a longing recognised by Hadjithomas, who says: “We keep thinking what kind of art can I do today? What can I do to continue? What is the place of art? What can art make of such situations?”

It’s not quite an answer but her husband adds wryly: “I just want to make flowers.”

Beirut and the Golden Sixties: A Manifesto of Fragility Gropius Bau, Berlin, March 25 to June 12.

Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf

News, FT and New European