The Book of Genesis 7; 4. God’s message to Noah: “I will cause it to rain upon the earth forty days and forty nights; and every living substance that I have made will I destroy from off the face of the earth.”

It’s tempting to see a world on the brink of divine destruction as the inspiration behind an exhibition at the Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, Italy, (until February 16) not least because it is titled Through the Floods but also because the first image to greet the visitor is that of Noah’s Ark. But the show’s themes, which are listed as “natural disasters; human abuse of animals and nature; man’s violence to man and the horrors of war; illness and death”, are not restricted to religious iconography, however potent.

The litany of catastrophe that has afflicted the world for centuries is reflected by the gallery’s choice of works, which date from a second- to third-century stele of a woman’s head in the style of Ancient Egyptian funerary monuments, through melodramatic representations of violence and disaster from the 16th and 17th centuries and on to shifts of style and emphasis in the 21st-century works, many taken from the last 10 years.

As curator Sara Piccinini explains: “There is something apocalyptic about the way we are immersed in a terrible flux, from floods and typhoons, to war and famine. There may be something Biblical about what is happening to the world but we are attempting to reflect the way the news is accelerating in intensity and for that we need to show contemporary work.”

That might explain why an early working title for the exhibition was Apocalypse Wow! Conceived during the pandemic, planned during years of unprecedented global tragedies such as typhoons in Taiwan, floods in the Sahel region of north Africa and the hurricanes that hit the USA, the show opened, with horrible irony, the week the first floods tore through Valencia, killing hundreds. It is coming to an end as fires rip through southern California.

While the show does open with After the Deluge (1864) by 19th-century Italian painter Filippo Palizzi, a traditional representation of the Noah story with the ark atop Mount Ararat and the liberated animals happily gallivanting around, a salutary note is struck by a radical version of the legend in Spoiler Alert (Extreme Weather) (2017-2019) by the American Andy Cross.

Inspired by Jacopo Bassano’s The Animals Entering Noah’s Ark painted in 1570, he shows how mankind has failed to deal with climate change and led by Noah (portrayed in this case as a Rastafarian farmer) the animals are to be deported in a 21st-century ark, a multi-mirrored space-age dome, to a planet where the inhabitants have accepted their responsibility to protect the world.

Given the show’s title, inundations and “weather events” are a recurring theme. A house in a painting from 1837 is swept along like some domestic ark by Alpine torrents, sailors flee from a storm-torn ship only to drown in the turbulent waters. In the deceptively simple Irene 2011 by Monica Bonvicini a wooden house, typical of the hundreds wrecked by that storm and many others such as Katrina and Helene, has been torn apart by the deluge. In stark black and white it is an understated image, but one that speaks of greater tragedies.

Back to the Bible: “God said unto Noah, The end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them… and, behold, I will destroy them with the earth.”

A graphic 19th-century print of The Plague in Florence, inspired by Boccaccio’s Decameron, is a nightmare of prostrate bodies pleading for salvation from the Almighty. A scene of despair and death overseen by a priest before a banner decorated with a skull and crossbones. He is holding a flaming brand – in part to protect himself from the disease, but also to ward off the plague carriers.

The fratricidal onslaught by Cain on his brother Abel is brought to life in Domenico Piola’s 17th-century Cain and Abel in a swirl of movement and colour. Cain, jealous that God had accepted Abel’s offering rather than his own, beats his brother to death with the jawbone of an ass. Looking on is a lamb, which signals the decline of human morality.

The inclusion of Fellice Boselli’s Macelleria (1720) seems an odd choice – it’s only a depiction of a butcher’s shop and of no offence unless you are vegetarian. But the sheer bloodiness of it, the carcasses, the staring lifeless eyes of the dead beasts is so brutal, so ugly, that you can almost smell the dead meat. It reeks of violence.

And then there’s the horror of war. In Metanarrativas No 1 (2024) the Cuban Ariel Cabrera Montejo has a young soldier wearing virtual reality goggles to observe a military massacre in which bodies have been strewn across a battleground. The painting drew inspiration from the 1898 war between the United States and Spain that ended in an American victory and Cuban independence, but it could be today. It could be Gaza, Ukraine or Sudan.

Photojournalist Ivor Prickett kept his camera trained on a woman in Mosul Old City, Iraq, at the height of the conflict in 2014. She sits on a plastic chair, waiting and watching as an excavator digs through the ruins of her home, sending swirls of dust over her, dumping mounds of stone and wreckage beside her.

Underneath the rubble, the bodies of her sister and niece who were killed by an airstrike. She did not move until the bodies were eventually found.

“Her defiance was one of the most heartbreaking and inspiring things I have ever seen,” says Prickett. “It seemed to speak volumes about the futility of war but it was also a testament to the strength people have in this fractured region.”

If she was phlegmatic in the face of tragedy, Käthe Kollwitz’s etching from 1903, Mother with Dead Child, is a primal scream of loss. Kollwitz sketched herself naked in front of a mirror holding her seven-year-old son Peter who was to die in 1914. Her aim was to dramatise the high rate of child deaths in her home city of Berlin where many did not live beyond the age of five.

With such imagery this is an exhibition shrouded in pessimism, despite the gallery’s insistence that there is some scope for optimism – or at least to take an equivocal view of the future.

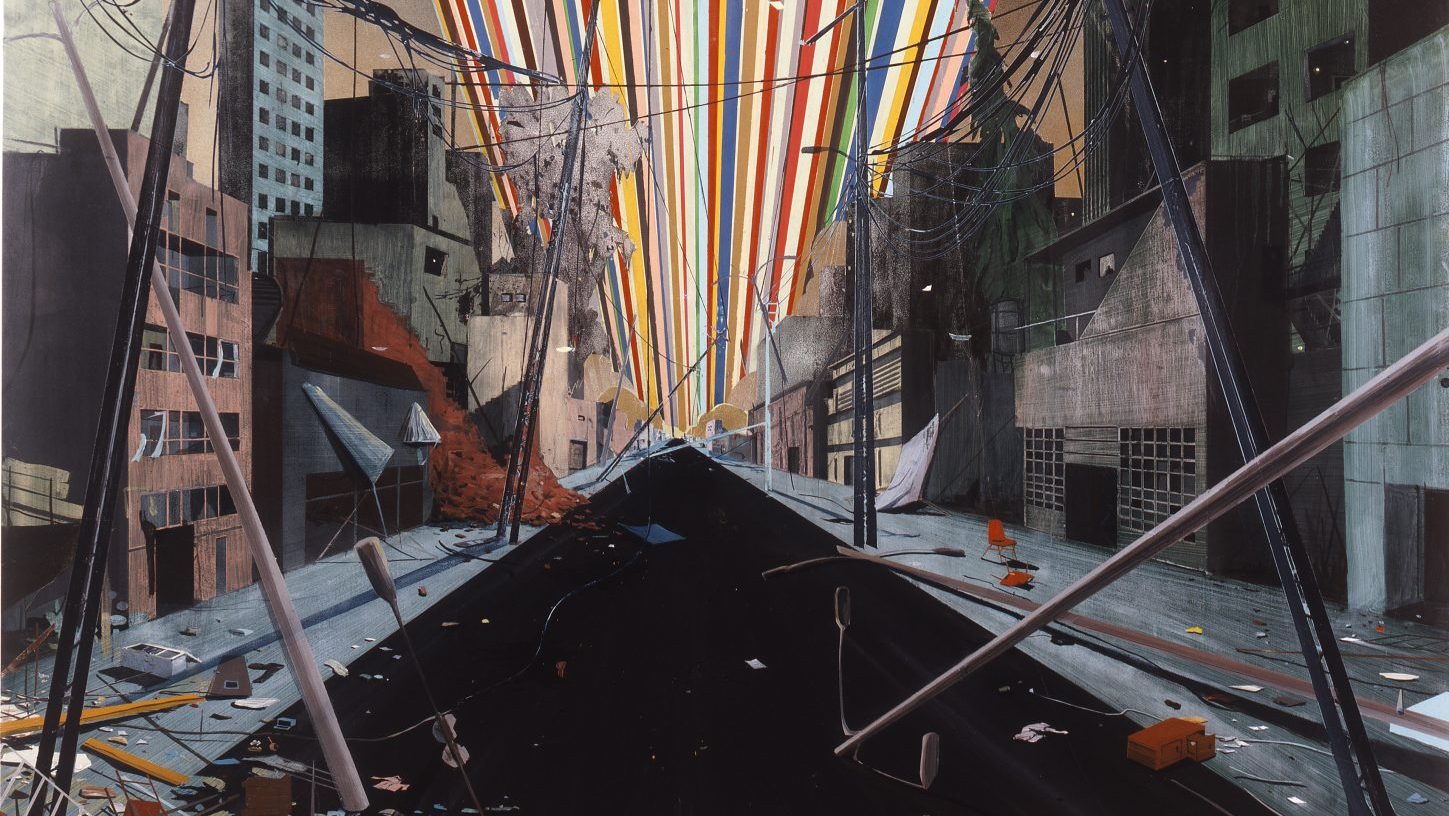

This ambivalence is best expressed by Jules de Balincourt’s startling Blind Faith and Tunnel Vision (2005). Set in a darkened room to heighten the dramatic effect, it depicts a wrecked street; buildings lurch, telegraph poles teeter, the chaos of destruction is accentuated by scattered chairs, debris and shards of timber. Has the destruction been wrought by the irresistible force of a storm or by human violence, a bomb attack perhaps? To add to the ambiguity a rainbow of stripes, beautiful but threatening, soars away into space.

Does it portend the end of the world or a bright new future poised to emerge from the ruins?

Those who take the darker view will find little comfort in Joan Banach’s Deep Water (1998), a disturbing painting of a woman with just her head above swirling, yellow waters. She is looking skywards but we do not know whether she is seeking help or is resigned to her fate.

Is the water an allegory for her unconscious dragging her down, sweeping her away on a tide of despair? Are we all not waving, but drowning?

Through The Floods is at Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, Italy, until February 16. More details: www.collezionemaramotti.org/