For most of his life, Antonio Calderara sought inspiration from the misty shores of Lake Orta, the smallest of Italy’s northern lakes, where houses rise like terracotta ziggurats from the water’s edge, streets are cobbled and narrow, church towers rise above town squares.

It’s tempting at first glance to dismiss these paintings as charming, pretty, but that would underestimate their subtle draughtsmanship, the way the planes of shade and light combine to create a sense of mystery, almost one of foreboding.

It was a style that won him years of steady success, but by the time he reached his fifties he announced: “In 1958… I drew my last curved line.”

And that was that. No more carefully crafted scenes of squares and quiet streets – instead, horizontal lines, vertical lines, enigmatic square and rectangular shapes often in pastel and invariably set against one dominant colour.

But not so fast. The change was by no means as clear-cut as his laconic statement might suggest as an exhibition at the Estorick Gallery, the north London gallery dedicated to 20th-century Italian art, demonstrates in Antonio Calderara; A Certain Light (until December 22).

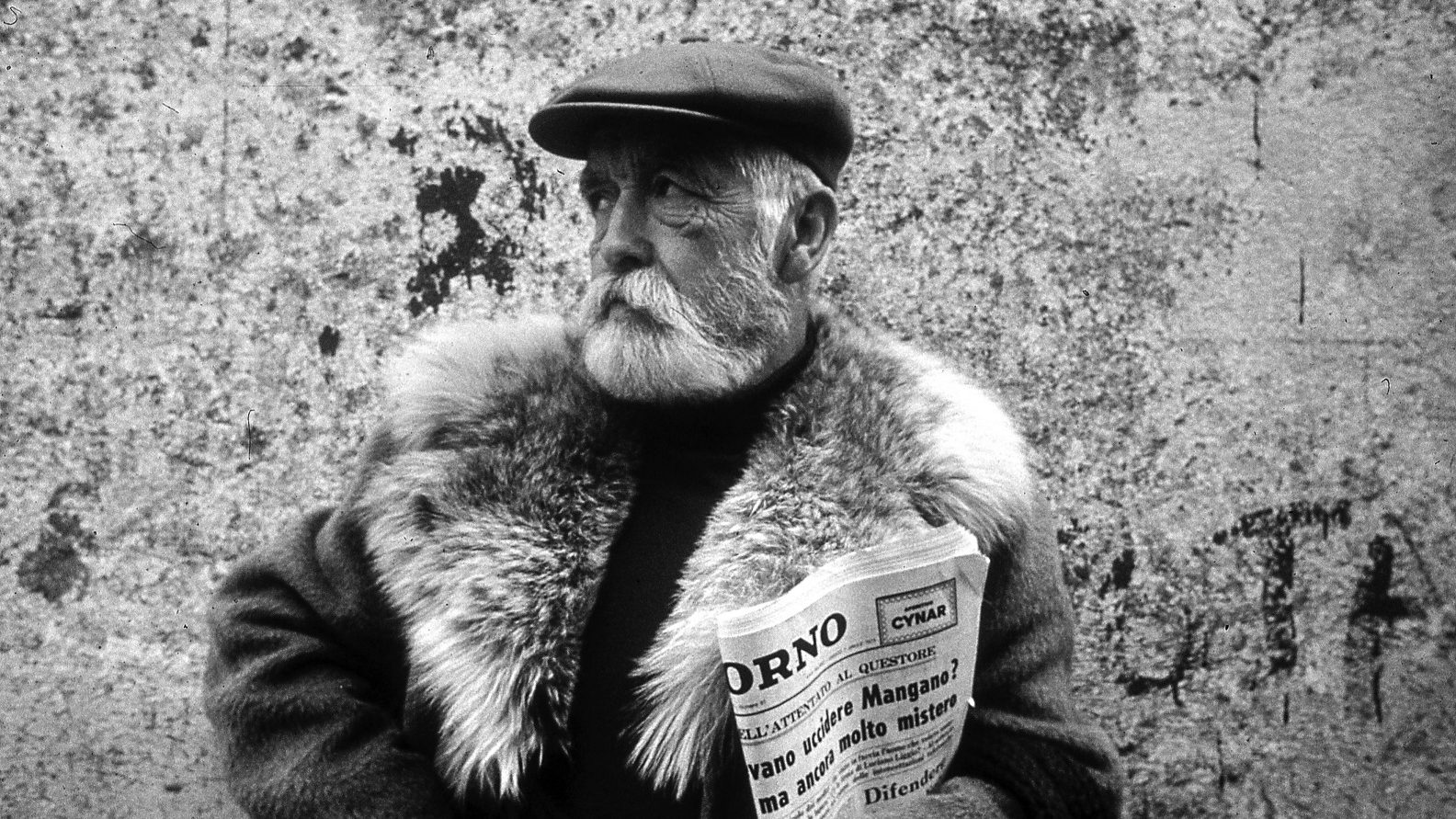

Calderara was born in 1903 in Abbiategrasso, south-west of Milan, before moving to Vacciago on the shore of the lake with his wife Carmela and daughter Gabriella, where he lived for the rest of his life.

He was self-taught, abandoning his studies as an engineer in 1925, and was mentored in his early years by Lucio Fontana, who was a family acquaintance, though none of his work reflects the slashed canvases that Fontana made his own, instead some of the early paintings are more reminiscent of Giorgio Morandi, particularly Natura Morta, and Georges Seurat in atmosphere, if not technique.

He was never really famous, he remained a loner whose work was considered by some to be a tad provincial. He did not run with the artistic pack who gathered in Milan and were gripped by the febrile world of Italian art in the years after WWI. Some rejected the violent imagery of Futurism, others embraced the traditionalist styles of the Novocento or gave short shrift to Pittura metafisica (Metaphysical Art), a movement created by Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carra.

Rather, Calderara said he owed his greatest influence to the simplicity and subtle light exemplified by the 15th-century Italian painter Piero della Francesca, something that is evident in the earlier works, geometric but with their hard edges softened with pastels of grey, ochre and faded reds.

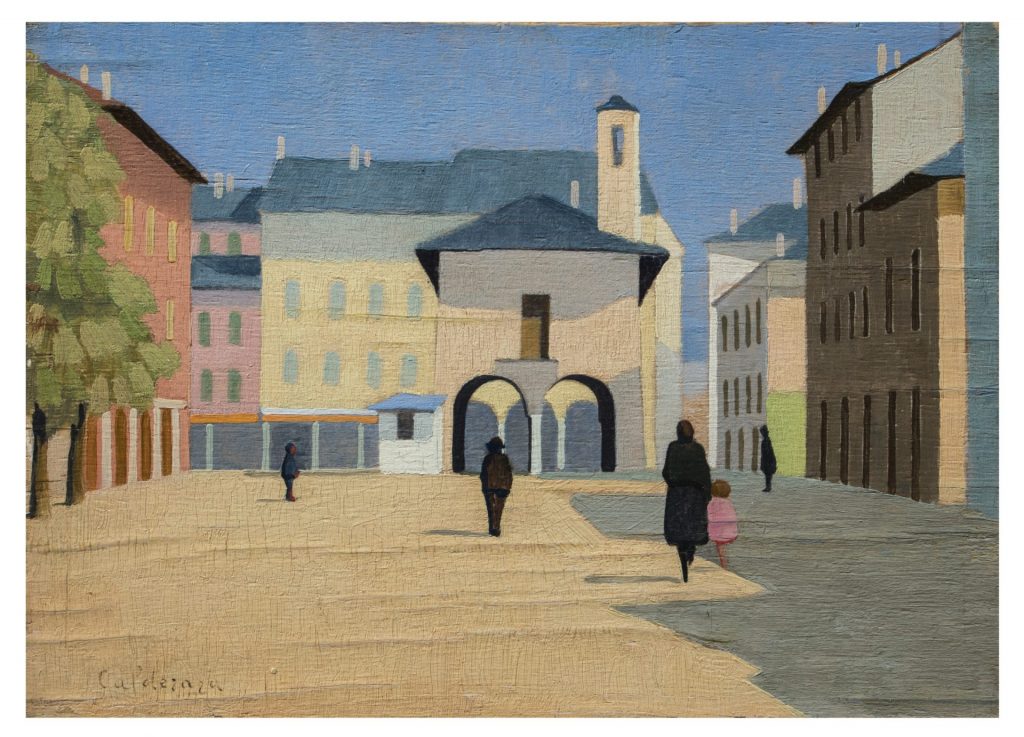

Take The Market Square in Orta (1929) in which the heat of the day positively bounces off the walls of the buildings, spreading a deep shadow into the square. Black-clad figures, a girl in pink, their backs to the viewer, are curiously immobile, keeping their distance – and their secrets. Despite their presence there is a strange emptiness about the square.

And again, in a scene across the lake (untitled) to the island of San Giulio which is framed by grey-blue mountains, the bulk of the church and campanile are carefully drafted but in the foreground a group of villagers, stand, all with backs to the easel, creating a similar atmosphere of disconnect and mystery.

There are signs of (abstract) things to come with The Factory painted as early as 1932 in which the low-lying bulk of the building and the slivers of two smoking chimneys almost disappear into misty nothingness.

By the late 1950s he was finding inspiration in the radical theories causing a stir in the USA, and in the likes of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg and Josef Albers. No doubt he was influenced by Ad Reinhardt, in what might be the rallying call for all abstract artists, who declared in 1962: “The one object of fifty years of abstract art is to present art-as-art and as nothing else…making it…more absolute and more exclusive—non-objective, non-representational, non-figurative, non-imagist, non-expressionist, non-subjective.”

Calderara was particularly impressed by the way Agnes Martin created her grids of horizontal and vertical lines to evoke a world of emotions and possibilities but the most significant influence was Piet Mondrian whose minimalist technique of straight lines and primary colours he first came across in 1954 when aged 51 and whose work inspired his dramatic rejection of the curved line.

Senza titolo (Piazza del mercato ad Orta). All images: Estorick

La famiglia. Dopo il temporale

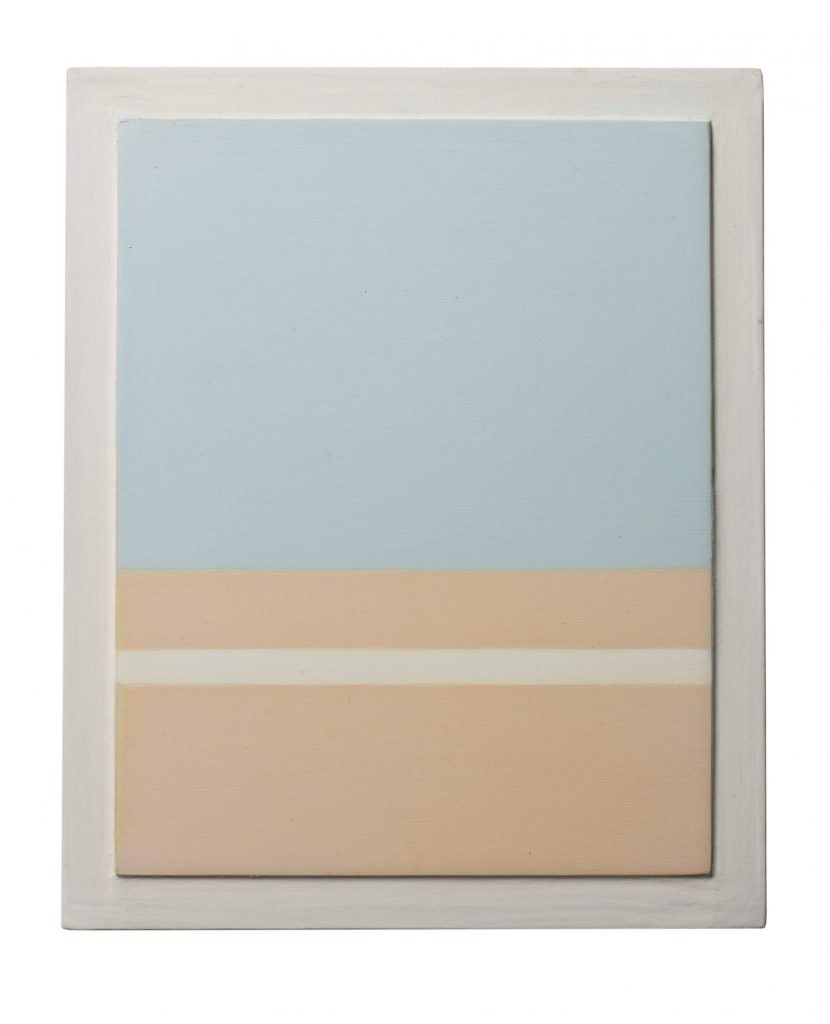

Pittura

To emphasise his progress from figurative to abstract, the curators have hung a winter scene (untitled) from 1951 alongside Painting – Winter (Snow in Vacciago) (1957–58). In the earlier scene the snowy hillside, the dark of the trees, merge with the ice-covered lake and the hills beyond. There is something of the abstract about it – it is certainly impressionistic – while in the later version the imagery is reduced to minimalist squares and rectangles of muted blue, grey and brown.

Other paintings are poised on the cusp of abstraction such as Contemplation, (1958) in which a figure, almost Christ-like, wreathed in the dull orange of a deep fog, holds what looks like a shovel. In The Bell Tower (1959) the narrow campanile is almost lost in the lines and rectangles and the nuanced pastel shades of the composition. It is framed by walls – a familiar technique of Calderara to enhance perspective – and one echoed in many of his abstract works including what was perhaps the first of his unequivocally abstract works Vertical Counterpoint in Red, (1959) in which the merest blush of pink is balanced by two narrow stripes of grey.

A series of untitled paintings using only horizontal bars of colour conjure up his new vision of familiar scenes, the mist and moods of the lake, but the imagery becomes more complex. One Untitled (1960) has a frame within a frame, the backgrounds are soft, off white, there is one rectangle of pink against grey, alongside another of the lightest grey barely contrasting with the lightest of pinks. In Attraction of Square into Yellow (1967), the greeny-yellow of the canvas is broken only by a tiny green square on the right side.

Some of these, often enigmatic, images invite the viewer in. Some coax, all challenge. Space Light (1961–62) is a deep, deep red. It demands you peer into its depths, where, what seems to be a solid mass of colour, almost conceals oblongs of reds in different, intense shades.

It is impossible not to be drawn in by Parallel Encounter in a Unit of Light (1960), its powerful black broken by two sets of grey in different strengths which perhaps reflects the intimations of death he must have felt after suffering heart attacks and the grief he still felt at the death of his daughter in 1944. So strong was his pain at her death, he ‘updated’ the portrait which hangs in the exhibition several times long after she had gone.

These paintings fulfill Calderara’s desire “to paint the void that contains completeness, silence and light. I would like to paint the infinite” and none does that with greater intensity than Constellation, painted in 1969. Pitch black with tiny grey and even blacker squares there is something Rothko-esque about energy it radiates with its luminosity and emotional pull.

As he wrote to a critic friend: “Structure and reason should never overshadow the emotion that I like to define as ‘poetry.’’

Antonio Calderara: A Certain Light is at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London N1, until December 22