The prospect of Donald Trump returning to the White House is supposed to have the world holding its breath – but in this year of elections, some of the planet has already exhaled.

Uruguay, Ghana and Romania are all due to go to the polls before the year is out, by which time almost half the world’s population will have cast their vote. Relief in Britain and France has been matched by dismay in the Netherlands and Austria. The global spread of the populism virus continues, and once more democracy appears to be in danger.

That message will have resonated deeply for Greece, Spain and Portugal, whose most recent elections as EU member states took place in the summer and for whom 2024 is especially meaningful.

This year marks half a century since the restoration of democracy in Greece following seven years of military rule, and in Portugal where the Carnation Revolution brought Europe’s longest-running dictatorship to an end in 1974. When General Franco died in November 1975, it brought almost 40 years of authoritarian rule in Spain to an end, so that all three countries began the transition to democracy at roughly the same time.

The National Gallery of Athens has honoured this special year with Democracy, the first major exhibition to explore this tumultuous period in the cultural and political history of southern Europe. It features 140 works by 55 artists, loaned by public and private collections across the three countries.

For audiences already familiar with the work of Picasso and Paula Rego, and to a lesser extent the Greek artist Takis, all of whom in some way denounced these oppressive regimes in their art, the exhibition reveals a diverse culture of resistance. It includes a remarkable range of work, from film, posters and paintings to sculptures and performance, and serves as a vibrant and inspiring testament to the power of art as a vehicle not just for political communication, but rage and pain, galvanised here as a sweeping story of political and artistic experience in southern Europe.

For gallery director and curator Syrago Tsiara, the exhibition comes at a moment of vital importance. She explains that since becoming director in 2022 she wanted to find a way to present Greek art in a broad geopolitical and historical context, all while keeping one eye glued to current world events.

“We’ve had a very smooth parliamentary history for the last 50 years in Greece, but all around the world and especially in Europe the extreme right has taken so much power, and there is such a lack of understanding about representation, elections and things like that. I believe it makes us all wonder about the future: we’re concerned about the young generation, and all the problems that have to do with democracy, including the climate crisis, which makes the refugee problem even bigger.”

As a result, the exhibition’s celebratory flavour is tempered with a sense of urgency firmly rooted in the here and now. “I believe that when we deal with subjects historically, we can better understand them, and how best to approach them,” she says.

Organised thematically, rather than by country, the exhibition emphasises the creative scope of artistic responses, that contrast with the modes of grandiose, classicising realism favoured by authoritarian regimes, and the shared motifs that recur across cultures.

The carnation is a symbol of peaceful revolution in Portugal and has a similar significance in Greece, says Tsiara, while barbed wire is used by Spanish and Greek artists as code for violence and the control exerted by their respective military regimes. In Vlassis Caniaris’s Belt, 1969, barbed wire crosses a plaster monolith like a Sam Browne belt across a soldier’s chest, while in a 1974 sculpture, the Catalan artist Jaume Xifra wraps a metal barrier in barbed wire, similarly suggesting brutal, public encounters with the regime’s enforcers.

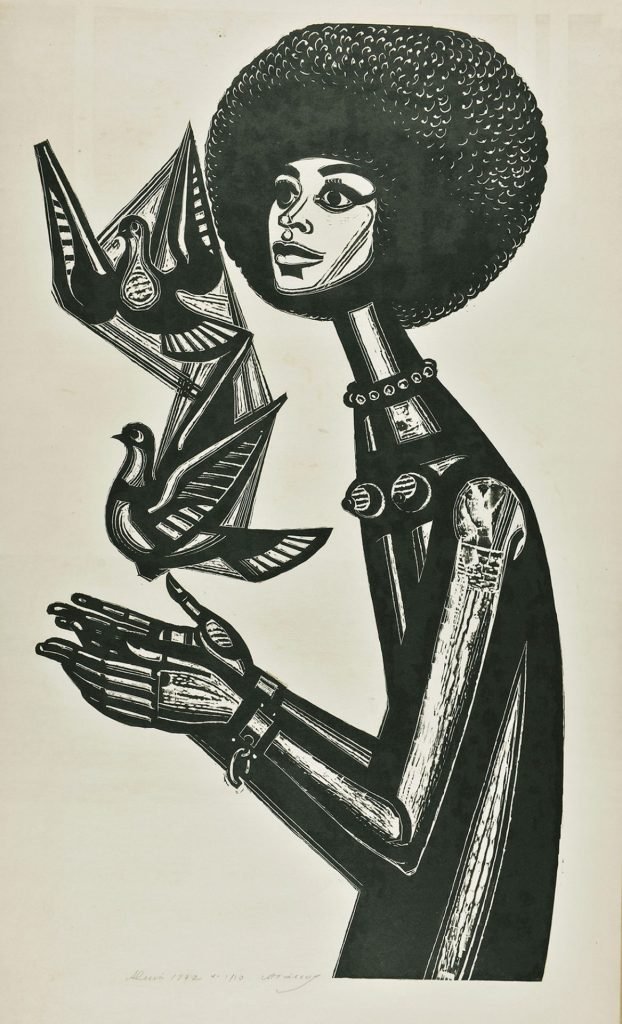

Both of these examples use contemporary idioms, but the Greek artist known simply as Tassos draws on the ancient legacy of Byzantine art in his woodcuts. In Cyprus 74, 1974, the style brings the weight of centuries of conflict to an image of a seated girl, whose path is blocked by spooling garlands of barbed wire.

These shared motifs reflect the desire for collective activity and feeling, says Tsiara, while references to the Vietnam war and to the death of Che Guevara also recur as expressions of global solidarity. Tassos uses the Byzantine style to bring religious authority to his tribute to the Cuban revolutionary leader, made in 1968, the year after Che’s execution.

Comprising two archangels with machine guns, their bodies wrapped in ammunition, they are a contemporary imagining of the warrior archangel Michael, who in Renaissance paintings especially is often depicted in armour and with a sword, defending the faith and leading the charge against Satan.

Syrago Tsiara singles out another angel warrior made by the Greek artist Giorgios Sikeliotis. Here the full frontal, archaic style expresses the aggressive femininity of a figure whose full breasts and long hair jar with the armoury of weapons at her waist, and her steady, confrontational gaze.

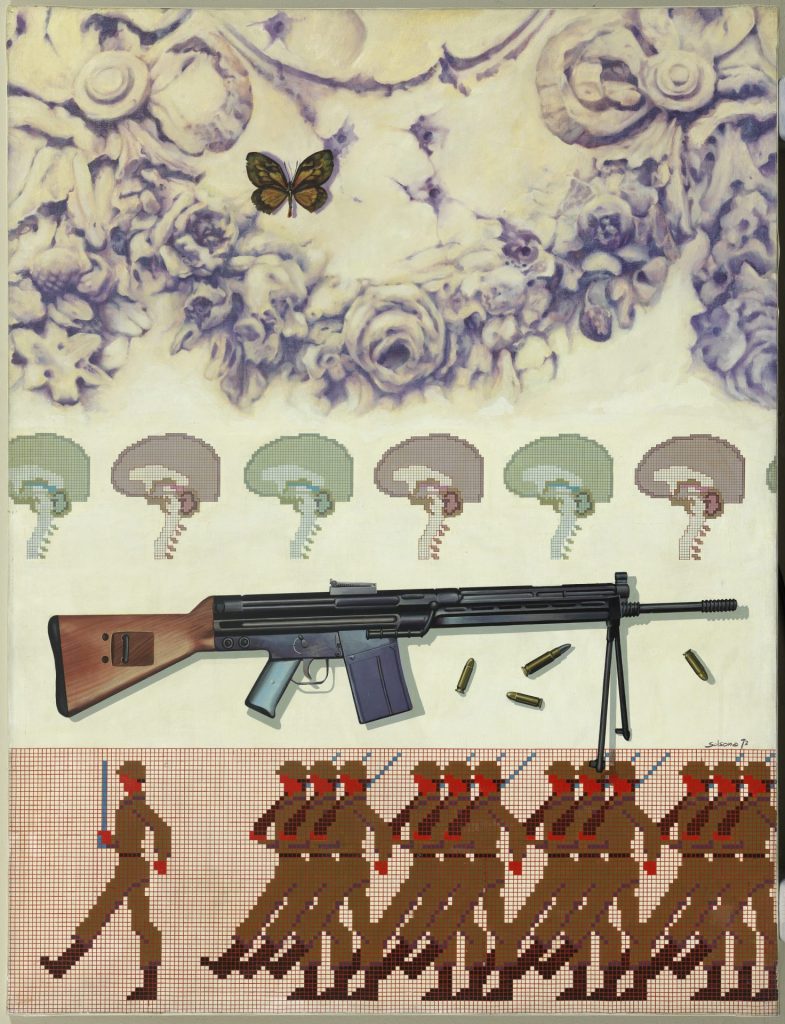

If anything, this particular angel warrior resembles the superheroes (albeit male) that were appearing in the anti-fascist productions of Estampa Popular, a network of Spanish art collectives that sprang up in the 1960s, of which the Valencia branch was among the most active. For them, pop art was a means not only of creating eye-catching images with wide appeal, but also of evading the censors through indirect and multi-layered references.

Even so, there is nothing subtle about Giorgos Ioannou’s Disciplined Freedom, 1969, in which bright colours and a “friendly” playschool pop art style present the Greek military junta as the obedient playthings of a neurotically anti-communist USA.

Pop art’s stock in trade is the witty subversion of images familiar to us from mass media, but in Eulàlia Grau’s poster Public Order, 1978, there is no wit, only a chilling sense of everyday life being weaponised to control citizens. The piece is like a catalogue, presenting without hierarchy photographs of a telephone, an aeroplane, the Pope addressing the faithful, all as examples of public order being maintained.

There’s a similar documentary instinct at work in Portuguese artist Ana Hatherly’s film Revolução, 1975, made on April 25, 1974 as the bloodless Carnation Revolution unfolded on the streets of Lisbon. The film catalogues the city’s revolutionary graffiti, posters and murals, emphasising the ephemeral nature of much protest art, which when combined with losses incurred by censorship and destruction seems to have left Portugal with a particularly diminished artistic legacy from this period.

It is often self-censorship that proves the most pernicious and effective curb on free expression under authoritarian regimes, and this is explored in two pieces from 1969 by the Greek artist Aleko B Levidis. He left Greece to live in Italy as a political refugee, and on his return to Greece he cut up his drawings and paintings in order to save them from the censor.

Once back in Greece he made collages from these fragments, summoning, he told Tsiara, “the ghosts of his artworks” in works that refer simultaneously to the violence done to free expression, and to people.

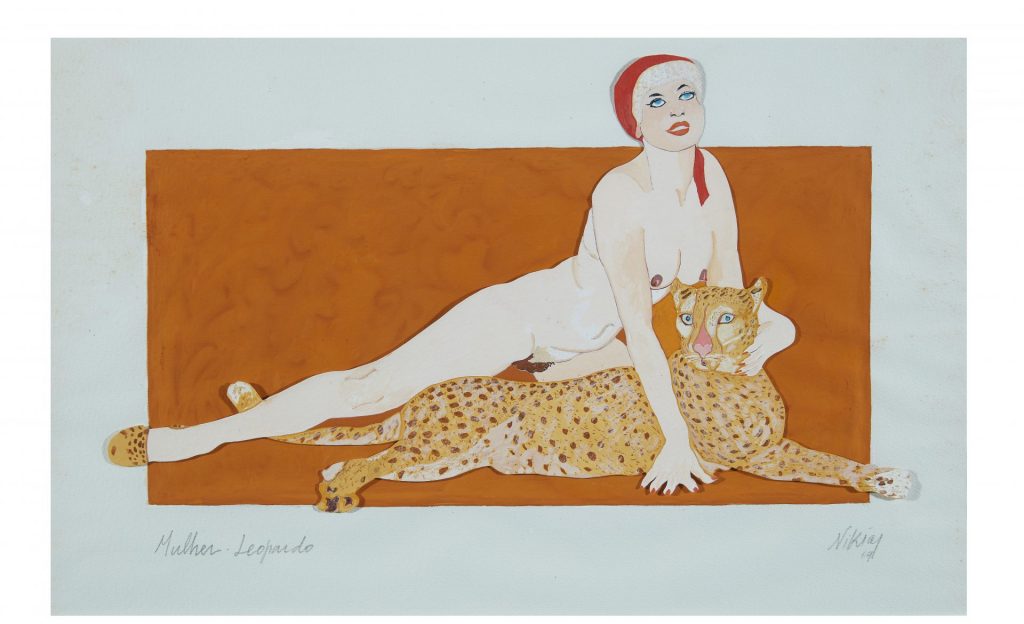

The threat and reality of physical violence was part of everyday life in all of these regimes, but the female body is a particular site of conflict, explored in a stunning series of paintings by the Portuguese artist Nikias Skapinakis. In works such as Bathers, 1971, he explores female sensuality and love, the painting’s non-naturalistic colours and scant facial features creating an inscrutability that works as a formidable show of strength and solidarity in numbers. The sexual aggression in Cleopatra and the Finger of Caesar, 1970, is countered and neutralised by the witty and disarming figure of Cleopatra.

Disempowerment is the subject of Greek performance artist Lēda Papakōnstantinou’s 1969 performance Votive, presented as a short film, in which we see a man’s hand marking a passive naked female body with black paint before replicating these gestures with a knife in a loaf of bread, making explicit a ritualised violence that as the title implies is somehow officially sanctioned.

Like many of the artists here, Papakōnstantinou was living outside her home country during its most oppressive years and this was the only way that her work could be seen. For Syrago Tsiara, this exposure was vitally important for Greece: “I think that artistic production is one of the reasons why the violent face of the Greek dictatorship was more obvious in Europe.”

She doesn’t limit her remarks to visual artists, and credits the composer Mikis Theodorakis, as well as certain politicians, with raising awareness of the Greek dictatorship in Europe. “I feel that art in general did a lot to make the face of dictatorship visible to the other democratic countries,” she says, and in so doing she makes a powerful case for art as an enduring advocate for freedom.

Democracy is at the National Gallery of Athens until February 2, 2025