One should never let a hellish global situation go to waste. I was reminded of this spirit when I recently attended the host event of an intriguing Franco-German alliance in Berlin. It was the fastest merger, Eric de Rothschild – one of the founding partners – jokingly said, he has ever experienced in his long banking career.

He alluded to the cooperation of two institutions, the French Projet Aladin and the German Abraham Accords Institute. Their joint goal reaches far beyond those two countries; in fact, it intends to bring people in the Middle East and Europe together.

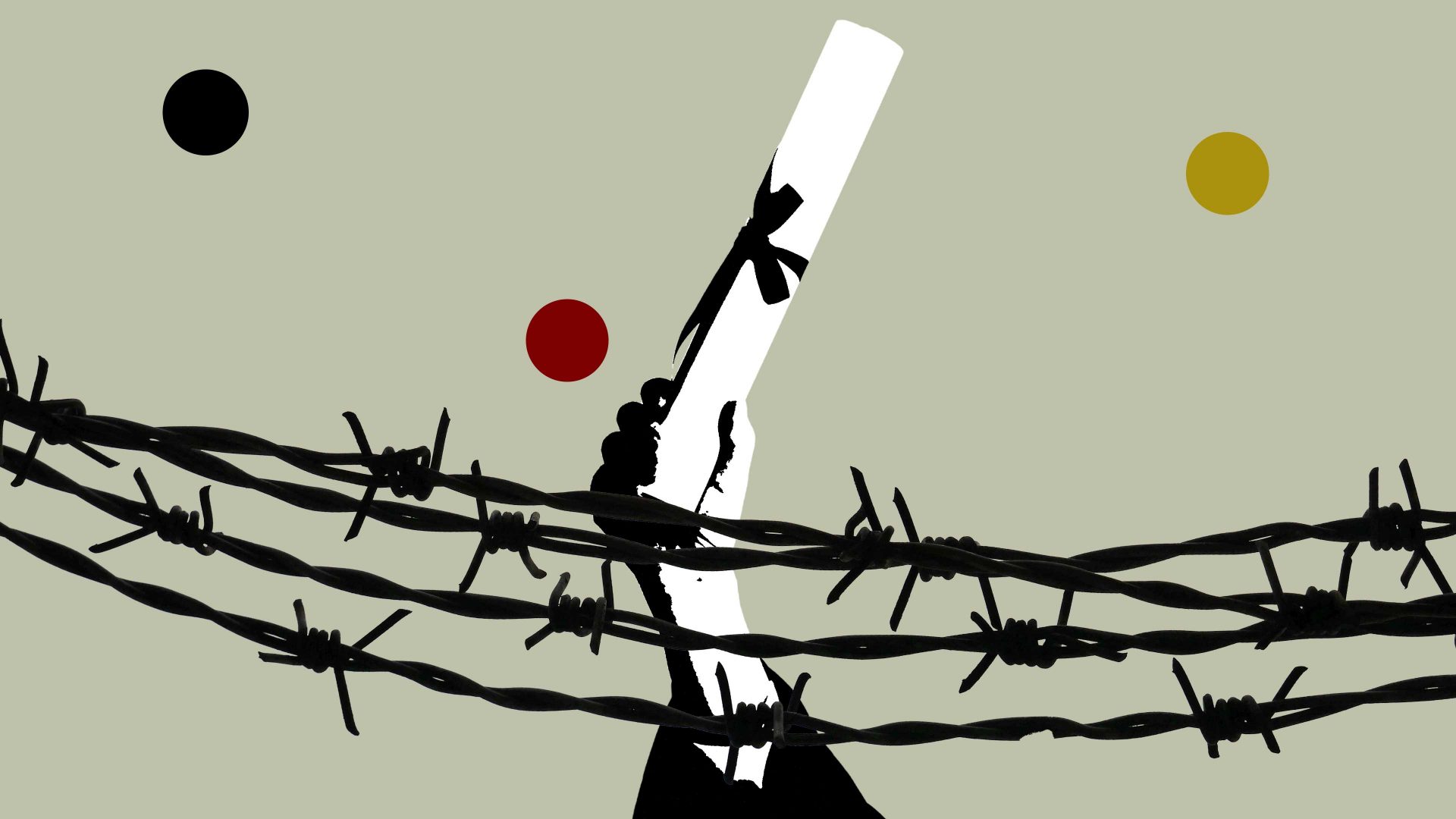

The idea was born after the Hamas attacks on Israel last year. Only a few months later, the newly founded “Committee to Counter Antisemitism and Xenophobia” is about to launch three specific projects.

First, a university exchange programme in which students and researchers from Israel can spend a semester or more in Egypt, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco or Sudan – and vice versa. Because there is a feeling that, while inter-state relations between these countries have been respectful and even friendly for a long time, the people aspect has been neglected.

Then through sports: a partnership with Paris St Germain, Manchester City, Borussia Dortmund and Fifa is planned, with football stars as ambassadors against hatred and racism. And through school: a training scheme for teachers with the EU and education ministries of member states.

The Aladdin Project has experience in education. When the then-president Ahmadinejad flooded Iran and the Arab-speaking world with hundreds of Holocaust-denial books, the Aladdin Library offered the first authorised translations of Anne Frank’s diaries to download in Arabic and Persian, as well as If this is a Man by Auschwitz-survivor Primo Levi.

Still, an Israeli-Arab exchange programme in wartime – isn’t that too ambitious? Actually, no. The Aladdin Project already organises intercultural leadership seminars for Arab, European, Israeli and Turkish students from more than 70 universities worldwide. And the Berlin gathering seemed confident that once the supply side was up, demand would follow – they are aiming to start in a year’s time.

“Right then, when war rages, we must not stop working for peace. I’m not pretending it’s easy,” says Dr Leah Pisar, head of the Aladdin Project (and half-sister of US secretary of state Antony Blinken), “but as civil society actors we have to prepare for the day after tomorrow, not knowing what tomorrow looks like.”

Armin Laschet, founder of the Berlin-based Abraham Accords Institute, recalls the legacy of French statesman and visionary Jean Monnet: “He recognised that we cannot change human nature, but we can change people’s behaviour, by transforming their actions from confrontation to mutual recognition.”

And so, from 1945 onwards, the former hereditary enemies France and Germany established thousands of town partnerships and exchange programmes for young people.

This, too, had been planned while war still raged. At a meeting of the French government-in-exile-in Algiers, Monnet had declared: “We must act before the enemy collapses. We must act now. We must be ready for that moment; before it comes is when the diplomatic arrangements must be made, before it that the peoples of Europe must be educated.”

Monnet stated this on August 5, 1943, nearly two years before the enemy did finally collapse. He added: “There will be no peace in Europe if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty, with all that that entails in terms of prestige politics and economic protectionism. The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the prosperity that modern conditions make possible and consequently necessary. They need larger markets.” Side note: one wonders how Monnet – in 1943 – could have had this foresight, and others… made Brexit happen.

Be that as it may: European integration is a proven model on how to set the course for a postwar period, but can it also serve the Middle East?

Israel’s former president Shimon Peres thought so. A French newspaper once asked him: “Who do you see as the greatest Frenchman?” The interviewer hinted at Napoleon.

Peres said: “No. I think Jean Monnet is greater… Why? Because Napoleon left after him a tomb, while Monnet left a cradle in which a new, peaceful Europe was born.”

And, impossible as it may seem today, why shouldn’t this work elsewhere, too? Best of luck, Aladdin and Abraham.