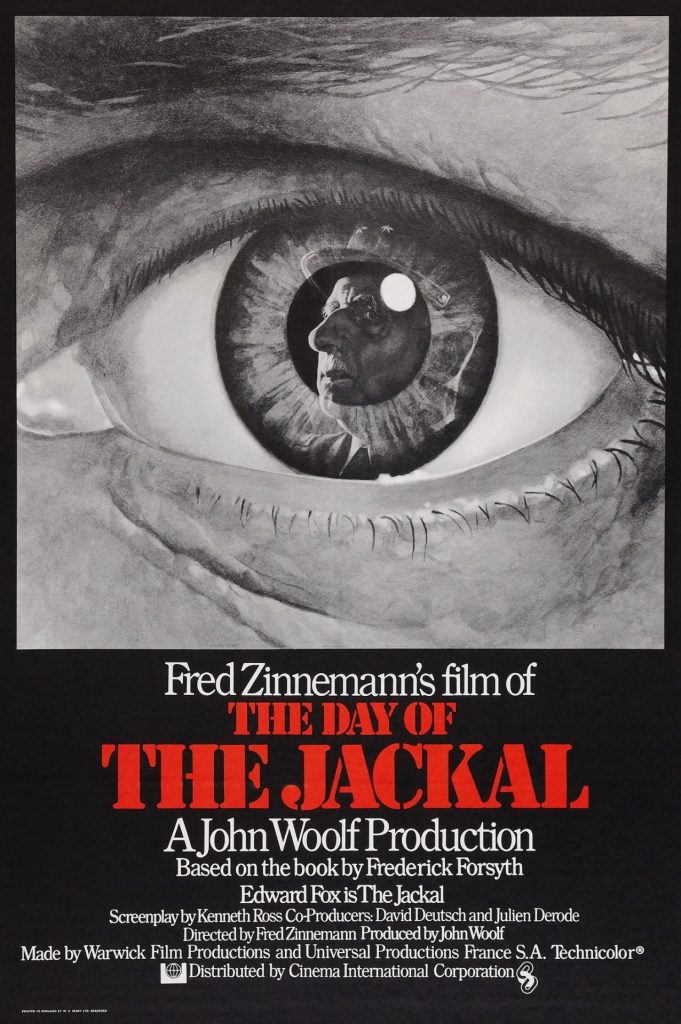

“I could happily watch The Day of the Jackal once a month for the rest of my life.” Not the words of some tragic obsessive, but the view of the man responsible for Erin Brockovich, Traffic and the Danny Ocean pictures, Academy Award-winning director Steven Soderbergh.

Such fulsome praise might seem a little surprising given that The Day of the Jackal is hardly regarded as a cinema classic today; on its release it underperformed at the international box office, and received just one Oscar nomination.

Look at the contemporary reviews, however, and you’d think that the picture was the movie event of the year. And, in a way, that’s exactly what it was. The director, Fred Zinnemann, had not made a film for seven years since winning the best director Oscar for A Man for All Seasons; his other credits – for which he’d won another three Oscars – included stone-cold classics like From Here To Eternity and High Noon.

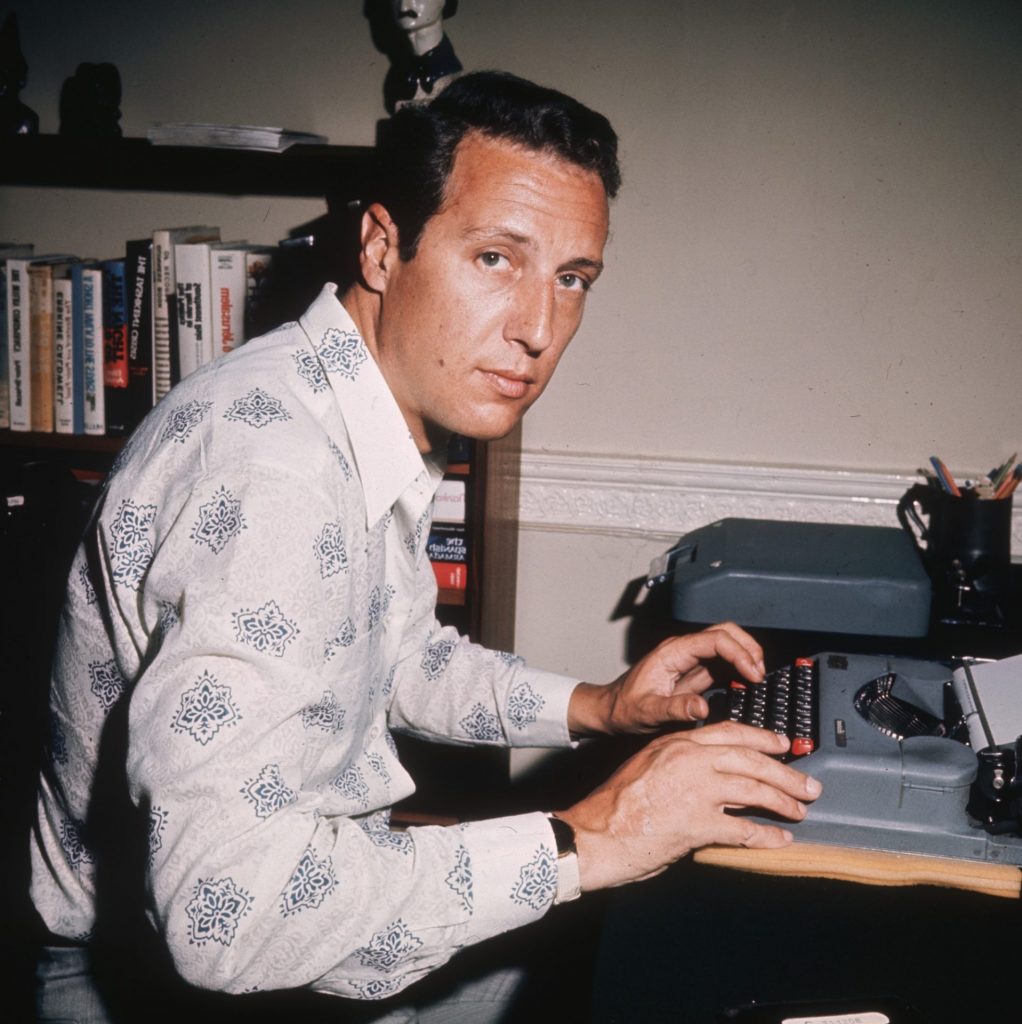

There was also the small matter of the bestselling source material; a detailed account of an attempt on the life of Charles de Gaulle coloured by the febrile political atmosphere of the 1960s. The author, Frederick Forsyth, was a journalist. At least, he was until the book hit the shelves. One look at the bestseller lists that first week of publication and Forsyth was a novelist; the most successful thriller writer of his age, in fact.

So what was it that made Forsyth’s book special? Why, the very things that would help the film stand out. While working for Reuters, Forsyth had covered everything from the crisis in Biafra to the Vietnam war. As a foreign correspondent, he also wrote at length about de Gaulle and the attempts made on his life by the Organisation Armée Secrète, or OAS, a right-wing paramilitary group dedicated to keeping Algeria French. They had come close in August 1962, when a hit squad fired 187 bullets into a motorcade carrying the president and his wife to Villacoublay military airport in the suburbs of Paris, but failed to hit anyone.

“Watching the concentric rings of security around de Gaulle, [I came] to the conclusion that the OAS were not going to kill him,” the author once remarked. “Most of the OAS were ex-army, which meant they were on file. Or they were white colonists from Algeria – neo-fascists!” If the OAS were going to eliminate the president, thought Forsyth, they’d need to hire a professional; a man whose attitude towards murdering a leading political figure was utterly devoid of emotion.

Forsyth kicked about this idea throughout his two years in Paris with Reuters. “I would come back to it in airport lounges,” he told the Spectator in 2010, “but I never thought I’d do anything with it.” But then Forsyth found himself back in London in 1970, broke, cold and burnt out. How to resolve this situation? By adopting an attitude not dissimilar to his latest creation.

“I’m a little mercenary,” he explained to DNA India, again in 2010. “I feel no compulsion to write. If somebody said: ‘You’re not going to write another word of fiction as long as you live’, it wouldn’t matter a damn. No, I wrote The Day of the Jackal for money.”

An awful lot of money, it would turn out. The bestselling espionage thriller of the early 1970s, The Day of the Jackal left the shelves so fast, copies were as hard to track down as the title character. As for the people the book spoke to, few heard it as loudly or as clearly as Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, a Venezuelan Marxist-Leninist with a gift for eliminating political figures. When a copy of Forsyth’s book was spied among his belongings, this, combined with his Latin American heritage, led to Sánchez becoming known the world over as “Carlos the Jackal”.

Though Carlos did his bit to bolster his sales, Forsyth ought really to have walked away from The Day of the Jackal wealthy beyond his wildest dreams. Accepting a flat fee of £20,000 for the film rights meant rejecting a second offer of £17,500 plus a percentage of the box office in perpetuity. As errors go, it’s right up there with the cardinal sins the Jackal commits in the novel.

Shortly before Forsyth flushed so much money down the loo, Zinnemann had a bright idea of the kind he often had over the course of his career. Born in Poland, raised in Austria and France, at home in both Britain and America, Alfred Zinnemann was a true citizen of the world. Fluent in French, English and German, his love of film flourished during an apprenticeship with Robert Flaherty, the trailblazing documentary film-maker famous for Nanook of the North.

It was thanks to Flaherty that Zinnemann became dedicated to the use of real locations instead of sets and the casting of “real people” alongside stars. As for his celebrated maverick streak, it’s possible that it stemmed from the tragic loss of his parents in the Holocaust. With his whole world taken away from him at a young age, Zinnemann was perfectly happy to take artistic risks, which, when weighed against the agonies inflicted upon his family, weren’t really risks at all.

The reward for this artistic bravery was a series of films familiar to anyone with even a passing interest in cinema. The Men, High Noon, From Here to Eternity, Oklahoma!, The Nun’s Story, A Man for All Seasons – no matter the scale or the genre, every manner of filmmaking was within Zinnemann’s grasp. It was in part thanks to his versatility that he secured four Academy Awards (from 10 nominations), a trio of Baftas, a pair of Golden Globes and the 1953 Palme d’Or (for From Here to Eternity).

Someone happy to take on any subject matter (though a superb western, High Noon is every bit as much a film about Joe McCarthy’s reign of terror), Zinnemann was also happy to take his time until the right project presented itself. After A Man for All Seasons dominated the 1966 Academy Awards, our man could pretty much write his own ticket. However, it would be six years before he worked again, and then it was only after a visit to his producer, John Woolf, ended with his taking away the galleys for a book by a new author. One quick skim through The Day of the Jackal and Zinnemann knew he had his next film.

But who to cast in the title role? Given Zinnemann’s knack for drawing performances from his stars that caught the eye of awards committees, it was no surprise that some of the biggest names of the era were keen to play the ultimate assassin.

“All sorts of people came over to audition for Fred. (Robert) Redford, the real big boys of the time; Jack Nicholson too, I believe. They all wanted to play the part. But bless his dear, dear, dear heart, he stood up for me.”

“Me” is Edward Fox, then a British actor with only a few screen credits to his name, now the head of a great acting dynasty. As the actor explains, it was one particular line from one particular movie that convinced Zinnemann he was the only man for the Jackal job:

“Fred saw a movie of mine called The Go-Between and in it I have a line that was ‘nothing is ever a lady’s fault’. And Fred said, ‘Anyone who can make that line believable has got my vote’!”

Nevertheless, it took six months for the director to convince the American co-producers to proceed with an unknown lead. They were eventually won over by Zinnemann’s conviction that “since this is a suspense movie, you really need to have an unknown actor as that will cast doubt over the film’s outcome. If you have a star, you know that in the end, things will work out for them. With a new face, everything is up for grabs.”

With his script, his “star” and the requisite cash, Zinnemann finally got down to work. He was assisted in this endeavour by one of cinema’s finest supporting casts. Tony Britton, Terence Alexander, Derek Jacobi, Cyril Cusack, Ronald Pickup, Timothy West, Anton Rogers, Alan Badel, Donald Sinden – to call it a who’s who of British and Irish acting greats almost feels like understatement.

And as befits a film spanning an entire continent, top European performers like Jean Martin (The Battle of Algiers), Michel Auclair (La Belle et la Bête) and Vernon Dobtcheff (The Spy Who Loved Me) were also on board, with the Anglo-French actor Michael Lonsdale doing both camps proud as The Jackal’s nemesis, the dour deputy commissioner Claude Lebel.

Surrounded by a wealth of acting talent and some of the best technicians in the business, Zinnemann – himself one the most disciplined and organised directors to have worked in the industry – pulled The Day of the Jackal together with relatively little incident. In fact, it was only when Forsyth showed up on set that the merest hint of pandemonium threatened to reign. Cue Fox:

“Fred Zinnemann wasn’t very keen about having anyone on the set who wasn’t integral to the film and so visitors weren’t terribly encouraged, and that included poor Freddie Forsyth! But he did arrive one day and we went and had a drink in a bar near the Place de la Madeleine. He said, ‘You’ll be surprised who you meet here.’ And I was surprised because it was full of hookers!”

Fortunately, Fox was far too busy to be led astray. As the actor explains: “Fred was a wonderful director and, quite rightly, very demanding. Every actor had to arrive on the set in their part. As you know, [The Jackal doesn’t have] a lot of words in the film, it’s all to do with feeling. I always thought it was the feeling of the man that was the important thing. I don’t know how you do that; you just think about it an awful lot.”

In fact, Fox spent eight months prior to the shooting trying to assume the mindset of a cold-blooded killer. Not that he had any qualms about playing such a ruthless character. On the contrary, “[As an actor] my job is to take a totally immoral man – a totally ruthless, greedy, brutal man – and make him likeable, otherwise the audience won’t want to watch him in the film. Why, you’ve even got to feel quite sorry for him at the end that he missed!”

Ah yes, that ending! It’s right up there with the audience hoping Marion Crane’s car will sink in Psycho, even though its disappearance might get Norman Bates off the hook. This, though, is the brilliance of The Day of the Jackal, a picture that leaves the audience obliged to see things through the eyes of the enemy.

And having made mention of one other classic movie, there’s also an interesting comparison to be made between The Day of the Jackal and The Great Escape, with each picture being obsessed with process. In the case of John Sturges’ war epic, this means we find out how the tunnels are dug and how the excavated dirt is dispersed. In Jackal, meanwhile, we discover how to get a new passport using the date of birth of a dead child (a tactic disgraced MP John Stonehouse lifted directly from Zinnemann’s movie before his disappearance), and how to pass oneself off as an ancient one-legged war veteran.

Despite such attention to detail and an absence of cheap thriller tricks – including the near-complete absence of a score – The Day of the Jackal didn’t initially deliver in the way the studio hoped. Maybe it was the fact that Fox was such a fresh face; or perhaps American audiences were worried that the European setting would mean spending two hours in subtitle purgatory – either way, Zinnemann’s picture enjoyed only modest success at the US box office.

The American critics, however, couldn’t have been more complimentary, with Roger Ebert stressing that, while the film is two and a half hours long, “it seems over in about 15 minutes”.

Over here, however, people seemed to understand that The Day of the Jackal was a big deal from the off. And as the years pass, so its reputation is revised ever upwards, with each new rip-off and the dire 1997 Bruce Willis remake serving solely to cement its reputation as an assassination movie without equal.

The Day of the Jackal is in fact so good that, even though they haven’t got a good word to say about Europe, keen Brexiteers Forsyth and Fox remain keen to talk up a picture whose creation is a great advert for European cooperation.

As Fox said of the film in a recent interview, “It still holds its head up”. But what would have happened if De Gaulle had done the same?

Richard Luck is a feature writer, critic and author of books including profiles of Sam Peckinpah, Steve McQueen and the Madchester music scene.