What comes first; the activist or the artist? It’s a question worth asking about this year’s Turner Prize.

For the first time, all five entries are from collectives who, in the words of the organisers, affected social change during the pandemic by constructing “pocket utopias… which replenish our reservoirs of hope”. At the same time – says Tate, the organiser – the exhibition aims to “promote public debate around new developments in British art”.

Well, does it? Is there evidence that the works which are on display at the Herbert in Coventry, as part of the City of Culture celebrations have affected social change? Can we detect groundbreaking work worthy of £25,000 for the winner and £10,00 for the runner-up?

Not really. All but one rely on video and installation to make their arguments, so nothing new there, while Project Artworks is the sole entry to highlight the work of painters – though that is not why I think it is the pick of the bunch. So, which is the more important? The art or the activism?

The exhibition’s lead curator, Hammad Nasar, has a ready answer. “It matter of opinion,” he says. “Artists have been involved with social movements throughout the 20th century and for years art has gone hand in hand with commitment, crusades and activism. It is a perennial question and the fact that it is being asked proves we are doing something right.”

Which, of course, is the safe reply but doesn’t answer the question; which came first, the chicken or the egg? Art or activism?

The causes espoused were chosen because they “reflected the solidarity and sense of community” during the pandemic, which means, apparently, that problems such as homelessness, the refugee crisis, poverty, climate change and war get short shrift. Instead what preoccupied the shortlist was colonialism, patriarchy, queer rights, abortion rights and a vague, overarching sense of injustice.

Where to start? Gentle / Radical is a group based in Cardiff run by artists, writers and community workers, who the jury admired for their commitment to the community of Riverside, where they live.

No doubt the judges were impressed by the impenetrable prose with which they describe their mission: “We want to work in ways that address the historical disinheritance – cultural, economic, political, spiritual, ancestral – of people who have yet to experience the power they are consistently told is available to them. Needless to say, we believe in the power of small nations, and in the radical potential of small, diverse, multi-lingual cultures to model at the cutting edge of equitable and sustainable 21st century futures.”

The result is more like a 1950s vicarage tea party which includes 100 minutes worth of video of individuals reading out their concerns, interspersed with a melodic choir practice in Welsh. Though, to be fair, teacups would have rattled at the reflection on how to “decolonise our parenthood” and create a village where parents could be “unschooled”.

If the Welsh entry is understated, Belfast’s Array Collective is a noisy, show-off affair whose aim is to “hitch our anger to causes” by supporting disenfranchised groups such as queer liberation, the Irish language and eco-politics.

The Array’s contribution is the Druthaib’s Ball 1921-2021 which is a boisterous denunciation of Northern Ireland’s misrule since its partition from the south 100 years ago. Druthaib translates as buffoon, and buffoonery is much in evidence on a video projected into a mock-up of an Irish síbin, an illegal pub.

It is wittily set up with a bar, round tables and booths for viewers to watch, for example, a woman in an outlandish gold wig and a helter skelter of a dress chants – ceaselessly – that she has “earned her divaship”. Loud, obvious, and for the participants it looked like fun, but as far as I could tell from the video the only people cheering, let alone looking on, were the members of the collective themselves.

We were treated to a dance by a plastic-breasted woman wearing a cardboard crown, and another exhibitionist hidden by a curtain of hair who railed against the hierarchy, the patriarchy, colonialism but more pertinently demanded changes in the abortion law and an end to women being treated as “little more than chattel”. A gay man delivered a monologue about living in a sectarian society riven with prejudice and made a quite good joke: “Orangemen like to dress up, so do fairies.”

There is a real sense that the Belfast bun fight is put on for their own amusement, something that cannot be said about the Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S.), a South London collective formed by and for QTIBPOC, an impressive acronym that spells out Queer, Trans and Intersex Black and People of Colour. Their role is to “challenge the dominant norms of sound system culture across the African diaspora through club nights, art installations, technical workshops and creative commissions” and by renting out their sound systems to community groups to promote ‘collective strength and encounter where kinship is found and reciprocated”.

In other words, have a right old knees-up with people or groups who might otherwise feel marginalised. Nothing wrong with that but it is a thin display, a video of dancers, a hard-to-hear recording of a B.O.S.S veteran explaining how to set up a sound system, all to the steady thrum of sound.

But they are a bolder bunch than their entry suggests. In 2018 they criticised the award’s main sponsor, Tate, for its handling of sexual abuse accusations by a black artist against a prominent donor and have since attacked redundancies made by the gallery during the pandemic. They even objected to being chosen for this year’s shortlist because they had not been given enough time to prepare for the event, attacking the “extractive and exploitative practices in prize culture”.

Nearly all of the entries are blighted by veritable jungles of tortured artspeak. But be brave, battle your way through the undergrowth that threatens to submerge Cooking Sections, a project conceived by Daniel Pascual and Alon Schwabe. They are described as a “duo of spatial practitioners (who) consider how space is constructed governed and managed… through the space of art they that they seek to enter non-art spaces”.

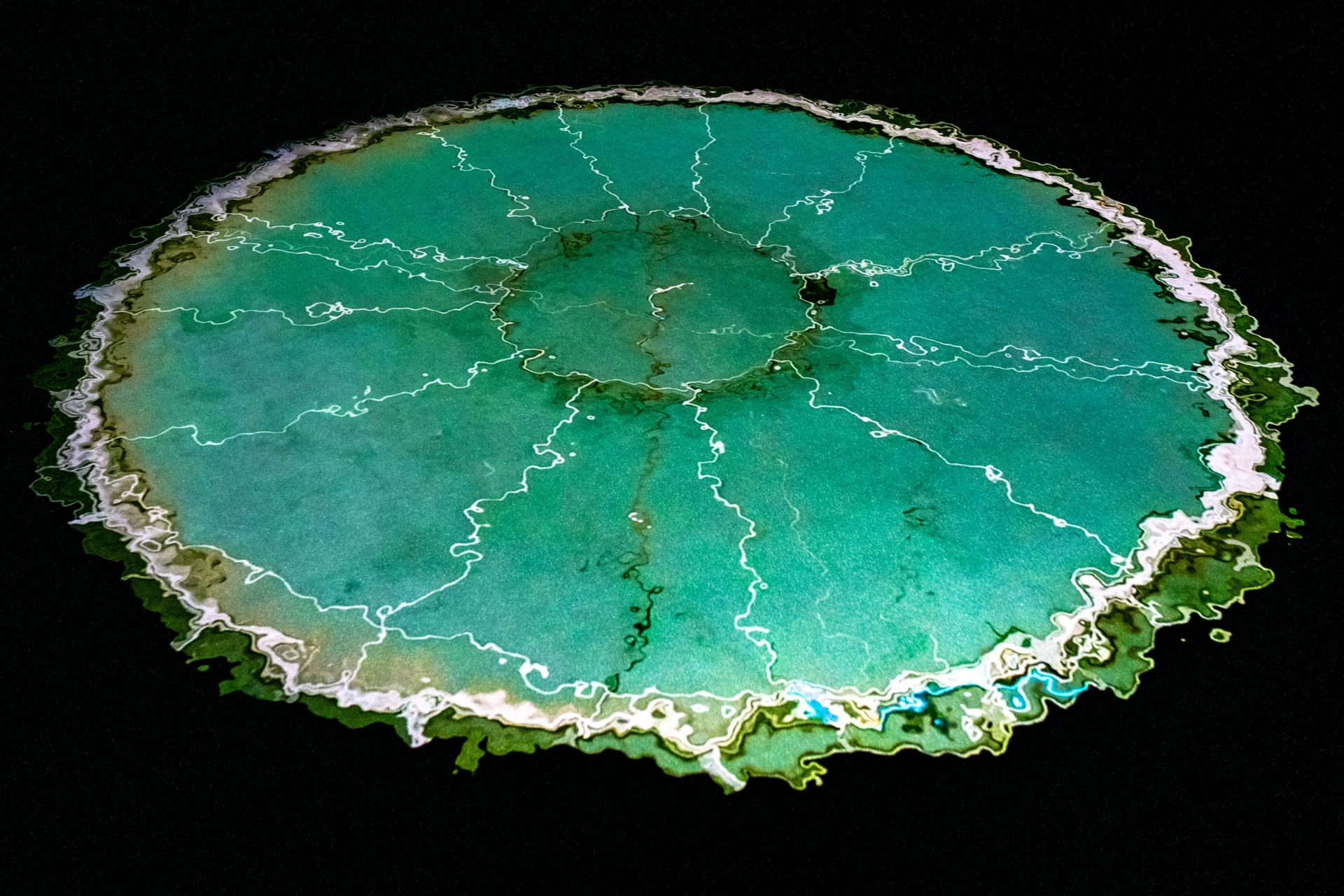

In fact, what they do is campaign against the cruelty of fish farming and provide a solution to the way food is grown and eaten. The ghastly fate of salmon is illustrated with eight aerial views of fish farms projected on to a darkened floor in which the fish are glimpsed flitting around their “oozy pens” at the mercy of pesticides, pollution and their own faeces.

In their project, Cliamavore: On Tidal Zones the duo demonstrate how food can be taken from the seas without destroying the environment. Set on the shores of Portree, Isle of Skye, an underwater rack used for farming the oysters emerges from the waves at low tide, to serve as a dining table with recipes featuring seaweeds, oysters, clams and mussels. When the tide sweeps in, the table disappears underwater to continue its role as a breeding ground for oysters.

So effective has Cooking Sections been that ten Scottish restaurants, as well as Tate and the Herbert itself have removed farmed salmon from their menu.

So far the cause has outweighed artistic creativity but with Project Art Works from Hastings, East Sussex, the two come together – art and activism combine to help young people with learning difficulties such as autism and a range of mental problems. Forty or so come regularly to the gallery where they find painting can be a source of self expression and therapy.

Impressive their work is too. One of the artists, Christopher Tite, a young man with learning difficulties, was at one of the press openings. He bounces on the balls of his feet, waving his hands anxiously, but reaches forward to add a bold dash of colour to his latest work.

Jack Denness has a striking self portrait on show; a bold tiger by Charlotte Stephens glares out; and a huge abstract by Carl Sexton dominates one wall while the vibrant circles of a Mandala, the symbol used in sacred Hindu and Buddhist rites, blazes from another.

This is the work of Siddharth Gadiyar who is severely challenged, yet he has discovered that he has a real gift – so much so that one of his mandalas was chosen for this RA Summer Exhibition.

The importance of this project is incalculable but the results are hard to define, with the Project emphasising that “very often the art is in the making rather than the object”. Some participants need guidance, others find an instinctive talent despite having no experience. For them, it becomes a form of interaction with other people which they would otherwise have struggled to make, and often too, it has a calming and nurturing effect.

This is not yet a ‘pocket utopia’ but again, to quote the Turner Prize, it is their ambition to promote “exercises in the real world that deploy the artistic imagination to propose a new, more equal, more hopeful futures”. That’s what Tite, artist in residence at the Herbert for one day, and his collaborators from Project Art Works are achieving. And for that they deserve to win.

Notorious Turner Prize moments

The one thing the prize has guaranteed since its inception in 1984 is controversy…

Malcolm Morley (1984)

The inaugural winner sparked a row because he had been living in New York for the previous 20 years.

Gilbert & George (1986)

Won for one of their trademark stained glass-inspired psychedelic collages, but tried to distance themselves from the grubby process of competition, saying: “We don’t like prizes. We are apart from all that.”

Richard Long (1989)

Some considered the rules had been bent a little too far, since the sculptor and installation artist was given the award for his lifetime body of work, rather than an exhibition.

Tracey Emin (1999)

Although it didn’t win, Emin’s My Bed – a double bed with stained sheets, surrounded by detritus such as soiled underwear, condoms, slippers and empty drink bottles – generated most controversy. Two artists, Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi, jumped onto the bed, stripped to their underwear, and had a pillow fight. Police detained the pair, who called their performance Two Naked Men Jump into Tracey’s Bed.

Martin Creed (2001)

His winning installation Work No. 227: The lights going on and off consisted of an empty room whose lighting periodically came on and went off. Artist Jacqueline Crofton threw eggs at the walls of the room containing Creed’s work as a protest. At the prize ceremony – live on Channel 4 before the watershed – Madonna handed out the prize, saying: “At a time when political correctness is valued over honesty I would also like to say ‘Right on, motherfuckers!’”

Fiona Banner (2002)

Banner didn’t win, but her entry, Arsewoman in Wonderland, generated the most comment. The wall-size text piece described a pornographic film in detail. Culture minister Kim Howells described the exhibits as “conceptual bullshit”, prompting an approving letter from Prince Charles. Graffiti artist Banksy stencilled “Mind the crap” on the steps of the Tate, who called in emergency cleaners to remove it.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo and Tai Shani (2019)

All four shortlisted artists were jointly awarded the prize after asking to be considered a single group.