Antoni Tàpies was 19 when his father gave him a copy of Lin Yutang’s newly-published anthology, The Wisdom of China and India, a book hailed on its cover as “a comprehensive treasury of the ageless wit and wisdom of the East”. It was the first step on Tàpies’ journey to becoming one of the most revered artists of the modern age.

Yutang called his book a “new synthesis of the mechanical and the spiritual, of matter and spirit”. Hoping it would become a tool to help repair a planet that was being shattered by the second world war, he had compiled (and translated into English, often for the first time) ancient Chinese and Indian texts that offered metaphorical and philosophical designs for living.

He set Hindu parables next to Confucian aphorisms. There were explanations of the I Ching (also known as the Yi Jing or Book of Changes) and

deep dives into the foundations of Buddhism. There were treatises on the

interdependent opposites of yin-yang, and the power of meditation and mysticism.

Tàpies was hooked. He was emerging from a disruptive childhood, having

survived the Spanish civil war and, aged 17, a heart attack caused by a bout

of tuberculosis that almost killed him. Two years on, here was a book that

would both help him understand the world around him, and become a source of inspiration throughout his career.

Tàpies was born into a comfortable middle-class family in Barcelona in 1923. His father encouraged Tàpies to follow him into a legal career, and he began studying law at the German School of Barcelona, taking art classes on the side. After just two years, Tàpies found the attraction of becoming a full-time artist too hard to resist, and the law studies were dropped.

In 1950, he won a French government scholarship that took him to Paris. The effect was transformative. Exposure to avant-garde mark-makers like Jean Dubuffet and the radical questioning of Jean-Paul Sartre and others propelled Tàpies from also-ran to race leader.

While his early work was derivative and in thrall of Surrealism’s legacy, Tàpies now rethought what painting – and art itself – meant. He threw himself into pintura matèrica (or matterism), the practice of mixing paint with, well, anything. Dust, dirt, gravel, cement, burlap – it all went in. This, Tàpies realised, was the alchemy of making art – the idea of celebrating and exalting the basest, most humble matter that he had read about in the second-century Buddhist texts in Yutang’s book. He started nailing everyday objects to his surfaces. Knives, shoes, and chairs.

The Wisdom of China and India was making sense and Tàpies was now in his stride. His premiere Spanish solo show followed the Paris trip, and by 1953 he was exhibiting in the United States. In 1957, Spanish curator Manyel J. Borja-Villel said of Tàpies: “His paintings present to us a world subject to constant change and metamorphosis, a world given shape – if only momentarily – by the artist-alchemist.”

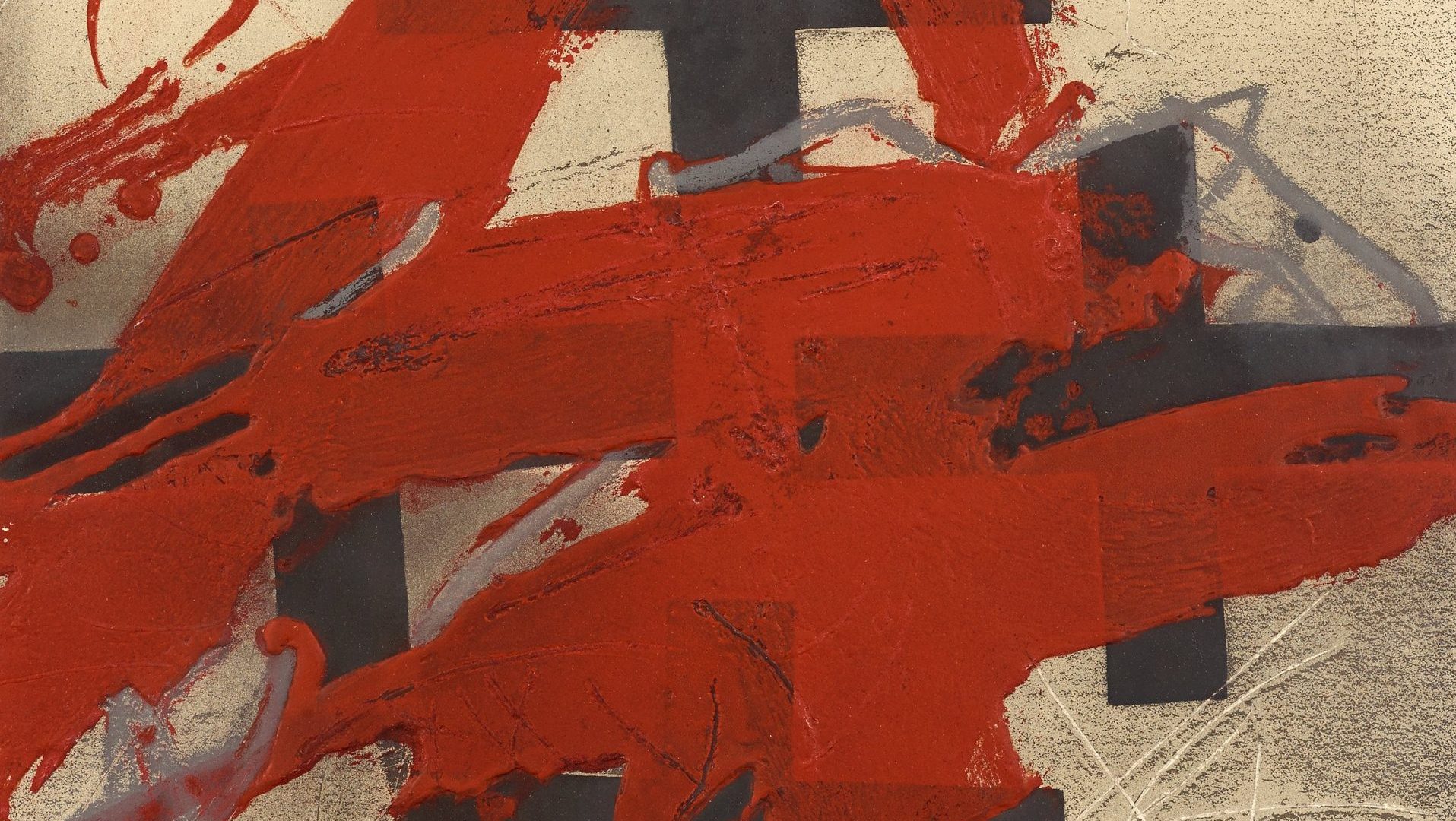

Yutang’s anthology had other effects. His inclusion of the I Ching influenced Tàpies’ paint palette, with white (the colour of simplicity, according to the

I Ching), black (the dirt of the earth), yellow ochre (a dragon and/or lightning), blue-black (creativity) and dark red (blood and the unfathomable)

becoming his predominant colours of choice. The I Ching teaches that the letter X is linked to the notion of change and progress. Tàpies’ work became littered with the letter X.

Furthermore, the book included tales of Bodhidharma, the sixth-century Zen Buddhist monk who, legend has it, spent nine years in a state of za-zen, or staring at a wall as a form of meditation. For Tàpies, a wall had stopped being something to hang pictures on, it was now a metaphysical opportunity and a portal to higher thinking. His 1960 artwork, Forma negra sobre quadrat gris, is nothing more than a head staring at a wall.

Tàpies took further inspiration from the I Ching’s concepts of Qi and Xu, both key components of yin-yang. Qi is the essential force that runs through all living things, and Xu is an emptiness or void. For Tàpies, Qi was the alchemical magic that happened during his artmaking processes, and Xu was the space of stillness from which things potentiate and continually change. Qi is the shout and Xu the silence. And one can’t exist without the other. In Carolina Tubau’s 2009 documentary, T For Tàpies, he explained: “Everything changes, never forget this. Nothing stays the same forever. This has left a mark on my work.”

Aside from his fascination with eastern mysticism, other elements shaped Tàpies’ artwork. His Catalan parents had instilled a strong sense of justice in the young artist, and his pieces were often dedicated to the fight of the underdog, especially in Franco’s Spain.

By the late 1950s, the new expressionist facet of abstract painting was developing as a way of portraying emotion in art. Mark Rothko’s oppressive tones, for example. Jackson Pollock’s exuberant confusion, and Cy Twombly’s angry stroke work.

If Tàpies had only used dense layers of matter in his work, his intentions of

expressing emotions from empathy to anger could well have been lost. However, Yutang’s book hadn’t just offered him spiritual insight, it was chock-full of symbols, words, and calligraphic diagrams that he could use to expand the meanings of his messages.

For Finestra, the artist gouged the phrase “32 marques” just to the right of a wooden frame pushed into plaster. In the I Ching, the number 32 represents

endurance, the ability to keep pushing forward to instigate change. Below the phrase, there’s a word that looks like prajnaparamita. In Buddhism,

Prajñāpāramitā is the way of seeing nature as truth. Finestra is Tàpies’

manifestation of a window through which life is viewed as a breathing reality, telling his audience that endurance will lead to enlightenment.

Tàpies died in 2012. He admitted that he had never achieved his own definition of true wisdom – the conjunction of samsara (the real world)

and nirvana (true reality). But that, he said, was not the point. Tàpies was a

munificent artist. Not only did his heavily textural, matter-laden technique push contemporary art forward at a pace, he also positioned his learning and philosophy so that it faced the viewer, without preaching or sermonising. He was trying to help.

In a 1994 interview with Unesco’s Serafín García Ibáñez, he said: “I feel

the desire, or rather the intense need, to do something useful for society, and that is what stimulates me. In every situation, I always look for what is

positive and beneficial for my fellow citizens. I am interested in study, reflection, philosophy — but always as a dilettante.”

The Fertiliser That Feeds the Soil exhibition showcasing artwork made by

Tàpies between 1958 and 1988 is at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, until

April 30, 2023