“I am always asked if I identify with the King,” said Yul Brynner in 1984. “It is

silly. It shows total ignorance on the part of the questioner. Life would not be liveable and acting would not be feasible if I came home from the theatre and approached my wife as the King of Siam.”

Some actors become so defined by a particular role the lines between where

actor ends and character begins can blur in the public perception. Bela Lugosi and Dracula, for example. William Roache, now in his 62nd year playing Coronation Street’s Ken Barlow. Jason Alexander and George Costanza.

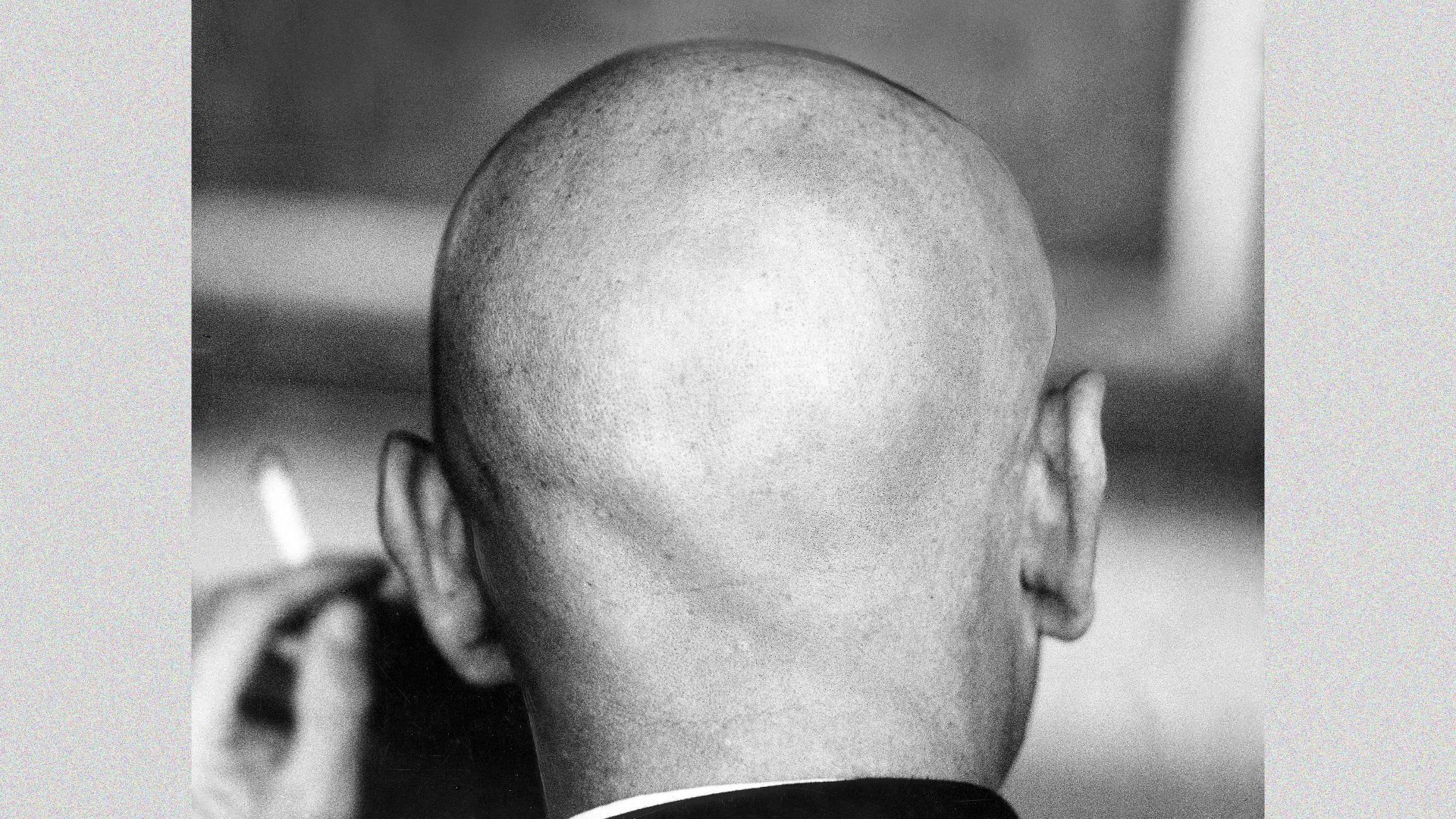

Placed firmly in that select group for his Oscar-winning performance as the shaven-headed King of Siam in the 1956 film version of Rogers and Hammerstein’s musical The King and I is Yul Brynner.

While the film is what defined him forever in the public consciousness, the stage show is what dominated his career. He played Mongkut, the King of Siam, an astonishing 4,625 times, the equivalent of performing every night without a break for 12 and a half years, and continued in the role even in the advanced stages of the lung cancer that killed him, his farewell appearance coming just four months before his death.

Yet these startling statistics are probably the least interesting thing about Brynner, who also found time to appear in a string of classic films from The Magnificent Seven to The Ten Commandments. He was an accomplished photographer, singer and guitarist, held two doctorates, attained a black belt in judo, spoke 11 languages, married four times and had a long affair with Marlene Dietrich.

“I don’t believe in being idle,” he said. “That is the only thing that would bore me.”

His life even before The King and I was extraordinary enough. Born Yuliy

Borisovich Briner in Vladivostok, the son of a Swiss-Russian mining engineer and an actress mother of Romani descent, Brynner was two years old when his father’s silver mining business was nationalised by the Soviets at the end of the Russian civil war. A few months later, in 1923, his father travelled to Moscow on a business matter, met an actress and moved with her to Harbin, China, forcing his abandoned family to follow him there in order to claim financial support.

In 1933, with war threatening between China and Japan, Marousia Briner relocated her brood to Paris where, at the age of 14, Brynner began performing Russian and Romani songs in nightclubs before joining a circus and spending most of his teens travelling Europe as a trapeze artist.

When a serious training accident ended his big-top career it triggered an addiction to opium as relief from the constant pain, forcing Brynner into a

Swiss addiction clinic. He checked out when his mother fell ill with leukaemia, accompanying her to the US for treatment and arriving in New York in 1940.

In characteristic fashion he immediately set about making himself busy, becoming an announcer on a French-speaking propaganda radio station broadcasting to occupied France, a presenter on Voice of America’s Russian-language service and commencing acting classes under Stanislavsky disciple Mikhail Chekhov, a nephew of Anton. He also found time to revive his cabaret act at New York’s Blue Angel club, where the 21-year-old met and began a relationship with the 40-year-old Dietrich.

His first stage role came the following year as Fabian in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night on Broadway, only for the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor to

close that and most other productions. When peace returned, Brynner, by then disillusioned with acting, began directing television plays for CBS before being persuaded to take his first significant film role as a drug smuggling kingpin in the 1949 thriller Port of New York.

Despite the film’s success, Brynner remained convinced his future lay behind the camera until in 1950 his friend Mary Martin, with whom he’d

appeared in a stage musical in 1946, all but frogmarched him to the audition for a new Rodgers and Hammerstein musical called The King and I.

Playing the same character more than 4,000 times might suggest an actor happy to coast through his career, yet Brynner never allowed himself to wallow in his global celebrity.

“When I am dead and buried I would like to have written on my tombstone:

‘I have arrived’,” he said in 1974. “Because when you feel that you have arrived, that’s when you are dead.”

He recognised stardom as a source of possibility, to live a comfortable life with a spectacular income, of course, but also the potential for bringing about genuine change.

In 1959 he began work he found more rewarding than any film or stage role.

Possibly inspired by his peripatetic early years, Brynner accepted a post as

special consultant to the United Nations high commissioner for refugees. For the rest of his life he worked on behalf of the disadvantaged, from the thousands displaced by the second world war to the Palestinians left in camps in the Middle East after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War to the Vietnamese boat people (he would adopt two Vietnamese refugees as his daughters).

Recognising the power of his fame in helping draw attention to the forgotten

plight of the displaced, Brynner travelled to camps at his own expense, listened to the stories of the refugees and ensured the world took notice, becoming exasperated when interviewers seemed more concerned with the impact on his career than the work he was doing.

“I believe it is far more important to help solve one of the world’s most terrible problems instead of worrying about how one’s screen career is

progressing,” he said in 1966.

In 1959 he directed and presented a documentary for CBS called Rescue with Yul Brynner which followed him on visits to camps in Europe and the Middle East and the following year made a similar film for the BBC, Mission to No-Man’s Land, which featured a particularly moving meeting in a Salzburg camp with an orphaned girl born in Buchenwald.

A renowned photographer, Brynner produced the book Bring Forth the Children in 1960, a series of pictures from the camps in which the occupants,

whatever their age, background, location and the cause of their displacement, shared the same beaten, glassy stare alongside Brynner’s moving written commentary.

For all the remarkable events and achievements of his life, Brynner was

always content for mythologies to propagate around him. He was the source of some of them, claiming variously that he was Mongolian, born

on Sakhalin, the largest island of Russia, and had fought for the international brigade in the Spanish civil war, always keenly attuned to feeding the power of celebrity that fuelled the work he did.

“I never deny anything,” he said. “Why? Obviously, the story the writer wrote pleases him so why should I rob him of that satisfaction? Even if I did deny a story the reader would only assume I was covering it up and I’ve never found any reason to do either.”