In the screwball comedy Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942), a hapless Ginger Rogers marries a Nazi aristocrat whose arrival “on holiday” in a European capital is routinely followed by Germany invading it. The comedy is driven by the fact that – as the spy drags her from Vienna to Prague to Warsaw – she can’t accept what’s really happening.

Xi Jinping’s visit to Europe last week followed basically the same plot. First he’s in Belgrade, declaring everlasting friendship with right wing authoritarian leader Aleksandr Vučić; then he’s in Budapest, celebrating a “golden voyage” towards shared objectives with Viktor Orbán, who has built a virtual one-party state in the middle of Europe. Then he’s in France where, despite the two countries’ deep disagreement over Ukraine, he is pushing the idea of Europe’s strategic autonomy as part of a “multipolar world”.

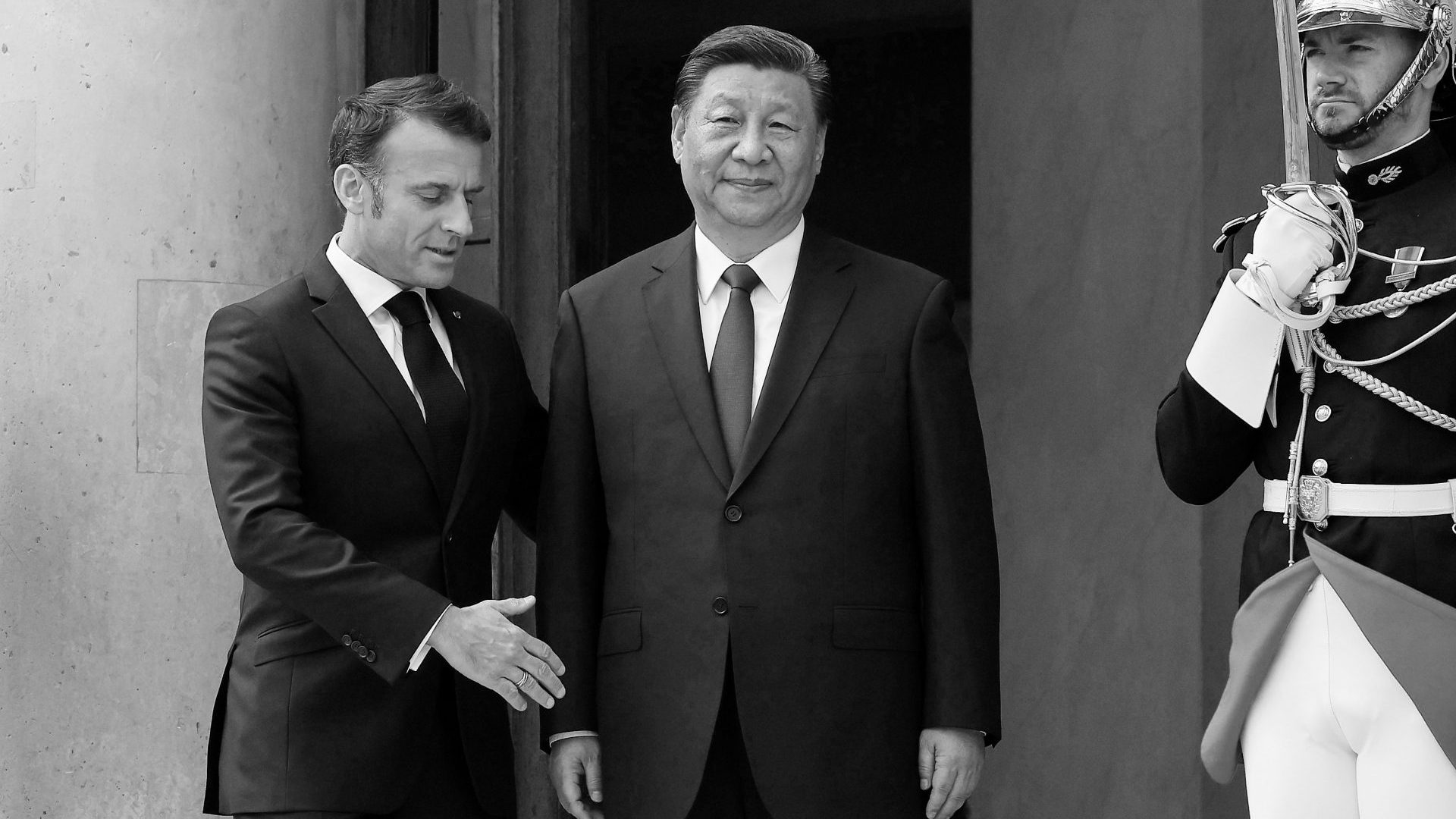

Xi, whose factories are shovelling drone technology, microprocessors and machine tools into the Russian war effort in Ukraine, told Emmanuel Macron that China is “not a party nor a participant in the Ukraine war, and only wanted peace. He quoted Voltaire in Paris, celebrated the music of Franz Liszt in Budapest and – coming up short of cultural references – marked his arrival in Belgrade with praise for a Serbian basketball player.

But the subtext is clear: Xi Jinping came to Europe on a divide and rule mission; to separate Hungary from both Nato and the EU; to link it to his client state of Serbia via a Chinese-funded railway, and flood the European market with subsidised electric vehicles, even if they are shut out of the US. And the horrible comedy of it all is that the EU has no viable strategy to resist.

The geopolitical stakes are clear. China’s avowed aim is to replace the rules-based international order with one based on naked power. As Xi declared alongside Vladimir Putin in February 2022, at the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, that means an end to universal human rights and the global rule of international law.

The three conditions for China’s ascent to global leadership by the mid-century are the decline of the US as a global power and the implosion of its democracy; the detachment of Europe from America, forcing the EU to deal autonomously with China as it extends its hard power throughout the Indo-Pacific region; and China’s intent to achieve global dominance in the next wave of technological innovation.

In this context, Xi’s play in Eastern Europe, which sees Budapest, Belgrade and Athens as staging points on China’s Belt and Road trade route, is a side bet. It creates a market for Chinese goods inside the EU, two dependent autocracies and, via Hungary, a wormhole into the Nato command structures. If it weakens the EU’s ability to act as a peer to China in the game of multipolarity, all the better for Xi’s overall strategic intent.

In the movie, there comes a point where, under the influence of hardball journalist Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers’ character finally accepts what’s happening and leaves the Nazi. Grant, in turn, uses a radio broadcast to warn the American people that, if the Nazis are not stopped, the US will be next on the itinerary. Suffice to say, western perceptions of geopolitical danger have not yet reached this moment of clarity.

I’ve been to China six times, on each occasion spending weeks, not days. I’ve studied the rise of its labour movement and the CCP itself. I have a profound respect for the Chinese people, whose culture – when it is allowed to speak openly – is as sublime, profane and riotously humanistic as ours.

I want Britain, Europe and the collective west to coexist on friendly terms with China as its economic rise continues. I want us to collaborate as strongly as possible with Beijing over climate change, global health and the establishment of international law in space, even as we uphold the law of the sea against Chinese aggression.

But what Xi Jinping brought to Europe was not a message of friendship and collaboration. It was a clear signal that he is trying to divide Europe in order to weaken it and separate it from the US, both in terms of trade and geopolitics.

The motivation is pretty clear. The Chinese economy is in trouble. Growth is weak and in some sectors there is deflation. Xi intends to dump billions of dollars’ worth of subsidised produce into any market that will accept it. And with Joe Biden on the verge of slapping new tariffs on Chinese-made EVs, solar panels and semiconductors – and a second Trump presidency threatening full-scale trade war – Europe is going to be the main target for Chinese exports.

In response, both the EU and the UK have some tough decisions to make. Macron’s Sorbonne speech, in April, signalled that he wants Europe to consolidate around the project of strategic autonomy, both in economics and geopolitics. That means acting tough against Russia over Ukraine, but, if victory can be achieved for Kyiv, appeasing China’s ambitions to extend control and influence in its backyard.

Britain, having finally summoned the willpower to protect its political system against Chinese money and influence, is about to see a change of government to Labour, whose primary objective in foreign affairs is a security treaty with the EU. But as trade positions harden, with the US, EU and UK all adopting the same, essential, state-driven green re-industrialisation strategies, Labour will need to define its attitude to China more clearly.

Labour wants to “de-risk” the UK’s economic relationship with China, challenge and compete with it over geopolitics and human rights, while collaborating over climate change. It’s about to find out how hard it is to do these things simultaneously and, as with Ginger Rogers in the movie, some early truth speaking wouldn’t go amiss.