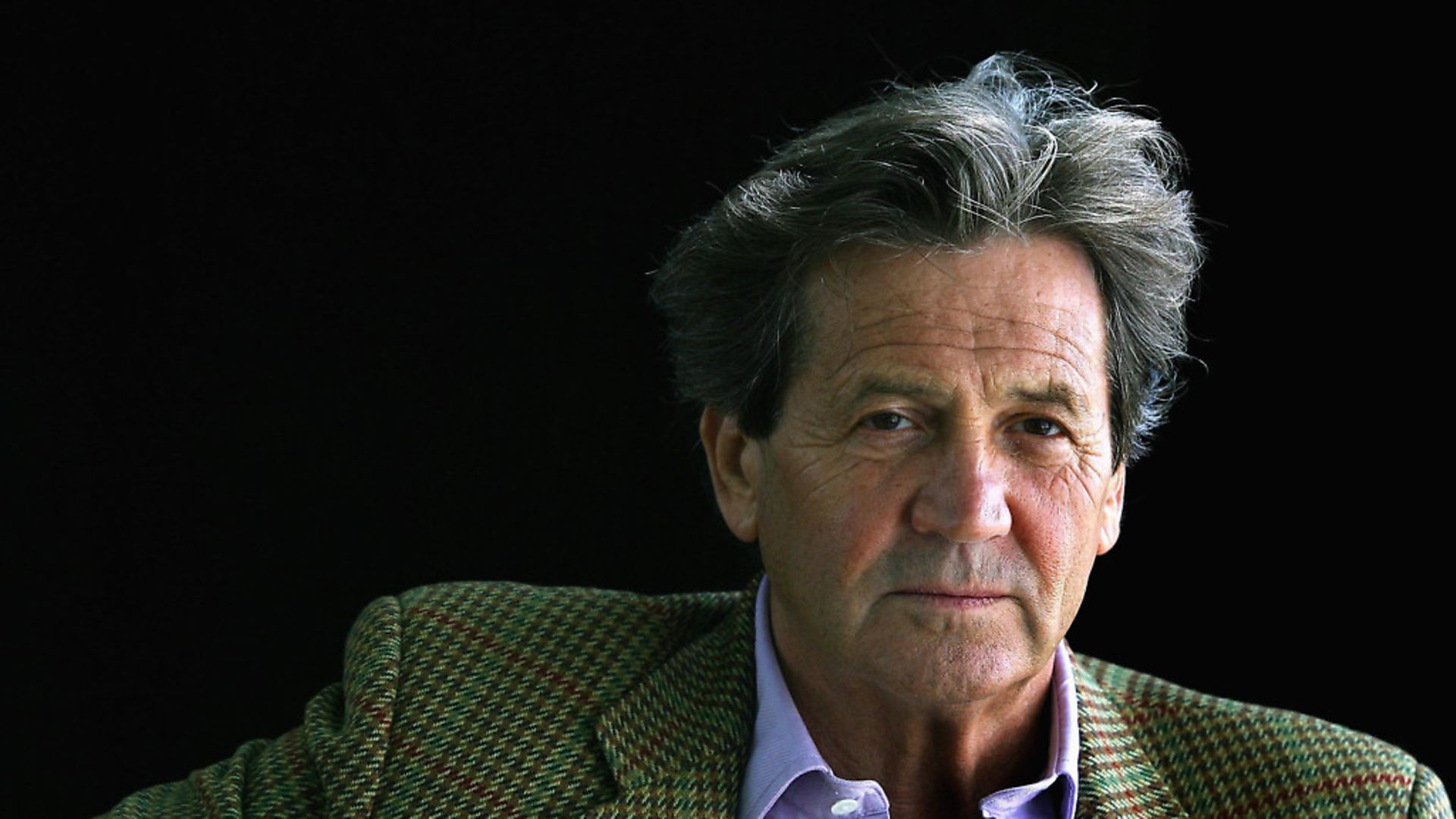

Melvyn Bragg – Lord Bragg of Wigton – is a vocal, avowed, almost evangelical champion of the BBC.

Having begun his career in 1961 as a general trainee at the corporation he is furious at the government’s threats to undermine it.

And as such, when we speak – ostensibly about the publication of his memoirs – he is unable to hide his fury at culture secretary Nadine Dorries in particular (we speak a couple of days before her appearance at the Commons digital, cultural, media and sport committee where she announced an independent review into the BBC’s funding while simultaneously prejudging an outcome which would see the licence fee abolished).

“I don’t think they know what they’re doing,” he says. “And every time this young woman who’s in charge at culture [Dorries, who is 65] opens her mouth you just think ‘I don’t believe it’. She doesn’t know anything. She doesn’t know this is private, she doesn’t know this is public, she doesn’t know what’s happened. I just think they want to take a swipe at the BBC and God alone knows why.” He stretches out these last four words.

“When you go round the world, which I have been doing a lot, they look back on this country with less and less respect. There’s some respect there – I mean, the monarchy’s always respected. The second thing that’s respected is the BBC. It really is, through the World Service or through everything else. There’s no institution like it anywhere. And the idea it could be replaced – there’s nothing like it. I mean, look at the intricacy and the number of programmes and the radio. It’s tailor-made for this country. It’s about this country. It sets the standard in this country. Now why they want to abolish it – and I mean this phrase – God alone knows, because I don’t. The Conservatives are conserving nothing at the moment.”

He dismisses the claims by ministers that the BBC needs to be more like the big US streamers, Netflix and Amazon.

“There’s absolutely no comparison. They do big, smashing programmes sometimes. They come in, the big boys, stealth bombers, and do the big programmes. Good for them. The BBC’s not like that.” He lists the sorts of cultural output the BBC puts out that the streamers don’t touch. “I’m not saying because the BBC’s so superior, but because the BBC’s so different. What they don’t seem to get is that the BBC is so deeply, idiosyncratically of this country for 100 years and it’s an extraordinary achievement. It’s probably our greatest cultural achievement. They don’t get it. They don’t listen to it – I mean, Johnson boasts he never watches television. Well it shows, I can tell you. It’s depressing. But, you know, we’ll just have to defend it, which we’re trying to do.”

Why doesn’t the BBC defend itself with the same vigour that Bragg is?

“I think they find it rather difficult,” he says. “At the moment they’re producing technical arguments – ‘look, it’s value for money’. But the day for the swords to be drawn and battle to be engaged is not yet on us. That’s a year or two ahead.”

I wonder if one issue is that the current cabinet seems to be made up of people with no cultural hinterland, Dorries’ airport novels and Michael Gove’s visits to Aberdeen nightclubs aside. Johnson himself appears to have no interest in culture.

“The politicians I remember from the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s … I mean, Tory, Liberal, Labour – they seemed to have a background that’s lacking with a lot of them nowadays,” says Bragg.

“Some of them have nowadays. But the idea of being a rounded person, culture being part of your education and part of the reason you went in … I feel you’re right, yes.”

We are actually speaking because Bragg has just published his first memoir at the age of 82. You, like me, may have assumed he’d long since written his life story, but this is his first, although he has published a series of autobiographical novels.

Why now, then, I wonder, given the publication of Back In The Day comes just two weeks before Love Island’s Molly-Mae Hague publishes her memoirs at the considerably younger age of 22?

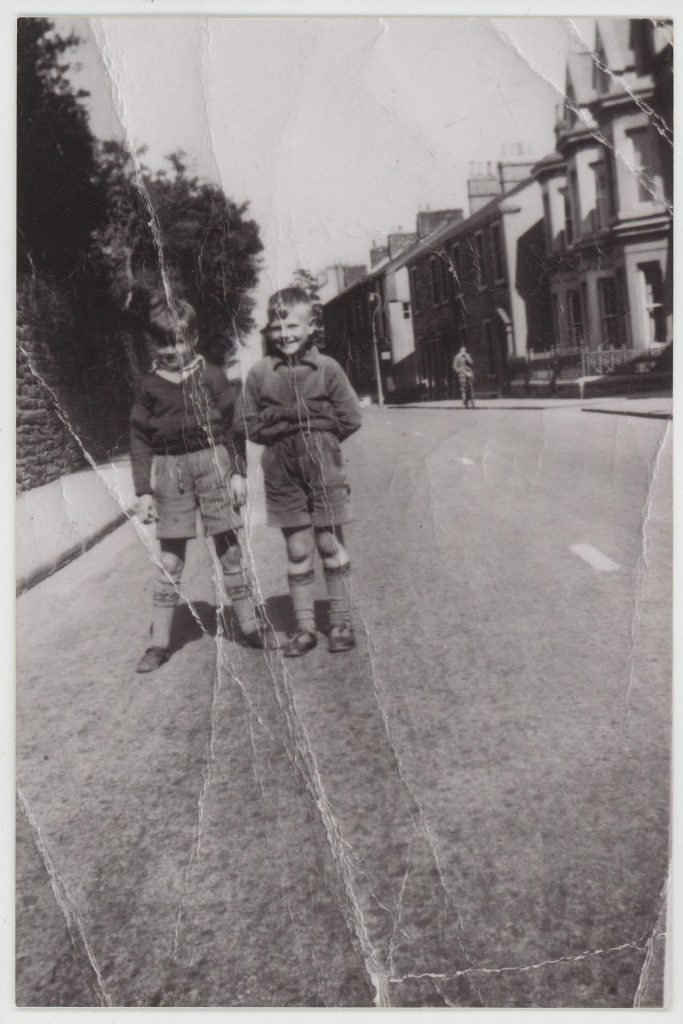

“I just thought that period of English life, the hinge in the middle of the 20th century between ’45, when my father came back from the war, came back to Wigton, and ’57/58, when I left Wigton, was a sort of hinge time in English life,” the broadcaster says.

“And it was a time when English people had to reassemble themselves after two enormous wars, one merciless economic breakdown in the ’30s, and pull themselves together and start all over again, as it were, putting it in a rather jovial way.

“And I was part of it. And I remember it with extraordinary clarity. I could have written that book three times as long – more incidents, more incidents, more incidents. And that town seemed to me, in retrospect, to be something that just needed to be explored. There are towns like that all over the world, in every country in the world, every civilisation in the world, towns of a certain size that satisfy people enormously. And that town, it was an extraordinarily satisfying place to live in.”

It is an overwhelmingly affectionate portrayal of Wigton, the small working-class Cumbrian town he grew up in (the reviews will call it “a love letter”, a description he welcomes). But particularly astonishing is the level of detail. The book runs to 406 pages and ends before he goes to Oxford University, and the detail – events, geography, conversations others would have long forgotten – is vivid. Does he have a photographic memory?

“I wouldn’t claim that, that’s a big thing to claim, but I have a very strong memory, particularly of my younger days,” he says.

“It depends on the sort of place you were brought up in – I was brought up in this extremely contained place. I think it was a real time in England that somehow imprinted itself on my mind. I don’t know … I remember more than I remember from my university years or my BBC years.”

Although it feels set up for a sequel, Bragg says he has no intention of writing a second volume.

“I’m not thinking of there being part two, no,” he says. “It might crop up in a few years’ time, but I doubt it. That’s what I wanted to write. Also, it says a lot about what I think about our country and it says a lot about all the things that matter to me. It says a lot about democracy, it says a lot about English people, the working classes … most of what I want to write about is there.”

One interesting aspect of the book is it is clearly written through the eyes of young Melvyn, with the author not using his hindsight to bring context to events. At one point, there is a disturbing turn of events where a stranger to the town asks a young Bragg for directions to the church, to which the boy takes him, only for the man to want him to dress in a cassock, and then to take pictures. The reader may be aware of his intentions, but the young boy, before running, only conveys a feeling something is not quite right, without knowing what.

“I didn’t set out to do that, but I did that,” Bragg agrees.

“When I started to write it, that’s what came out and, yes, that’s what I wanted to do, I discovered. You often write things down to learn what you know. And it was like that, it was through this young boy’s eyes. Through his eyes I saw the town, through his eyes I saw the clubs, through his eyes I saw the incidents. And I didn’t want any hindsight. I didn’t want to say ‘the town moved on …’ I wanted it to be a chronicle of ‘this is what we were like’.”

It’s also very much the story of the teacher who spotted the academic potential in Bragg, encouraged him and then effectively lobbied his father to allow him to stay on at school and eventually university, something which, at that time, was still highly unusual in working-class towns. Did writing the book allow him to reflect on what might have been (or might not have been)?

“Yes I do,” he says. “I would have left school at 15 with reasonable if not particularly good O-levels and I’d have had options. I might have gone down to the factory and, because I was reasonably good at maths, worked in the accounts department as one or two of my friends did. Or gone into local government at a very low level. Or something like that.

“But those were the jobs that my friends did and they had good lives. And I kept up with them all their lives. Alas, too many of them are dead now.”

It might also be, I suggest, one of the last ‘working-class boy made good’ memoirs. Writing about class, and leaving behind a working-class background, seems unfashionable if not quaint in an environment when stories of overcoming attitudes to race, gender and sexuality have much more salience.

“I think you make a good point,” he says. “But I just ignored all that and got on with it. But you make a very, very good point. But that was my time. And that was a time in England that was like no other time.”

Bragg, who became a Labour peer in 1997 after giving the party two donations of £7,500, was an outspoken critic of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, denouncing his “feebleness” on tackling antisemitism and branded his failings a “disgrace”. On Keir Starmer he is supportive if, it feels, rather tepid.

“I think he’s having a good go,” he says. “I think it’s very difficult if you’re in front of this bombastic … I’m afraid I have to say this but it’s true, proven – I mean, it’s awful to have to have to say this about a prime minister, but globally he’s known as a liar and a blusterer and somebody who’s used to getting away with it and he seems to be getting away with it again. And it’s difficult to know what to do against people like that.

“He has his moments, but Starmer’s got this sort of steadiness, like Attlee, really. But he’s in a difficult world. We’ll see. I think he’s doing ok.”

Other than that, Bragg remains busy. The South Bank Show, now shown on Sky Arts, returns later this year, and of course there’s In Our Time, the unashamedly highbrow Radio 4 discussion series which next year Bragg will have presented for a quarter of a century.

Which is my opportunity to tell him of my only issue with the show – historians who speak in the present tense (“Gladstone is thinking that this is an opportunity for his home rule agenda…”).

“A lot of people do,” says Bragg. “It’s very strange, isn’t it? It gets under people’s skins, it really does.” He laughs. “You can’t tell them off. I mean, they’re emeritus professors. You can’t say, ‘just stop that now’.”

Back In The Day is published by Sceptre, priced £20 hardback and eBook, £19.99 audio