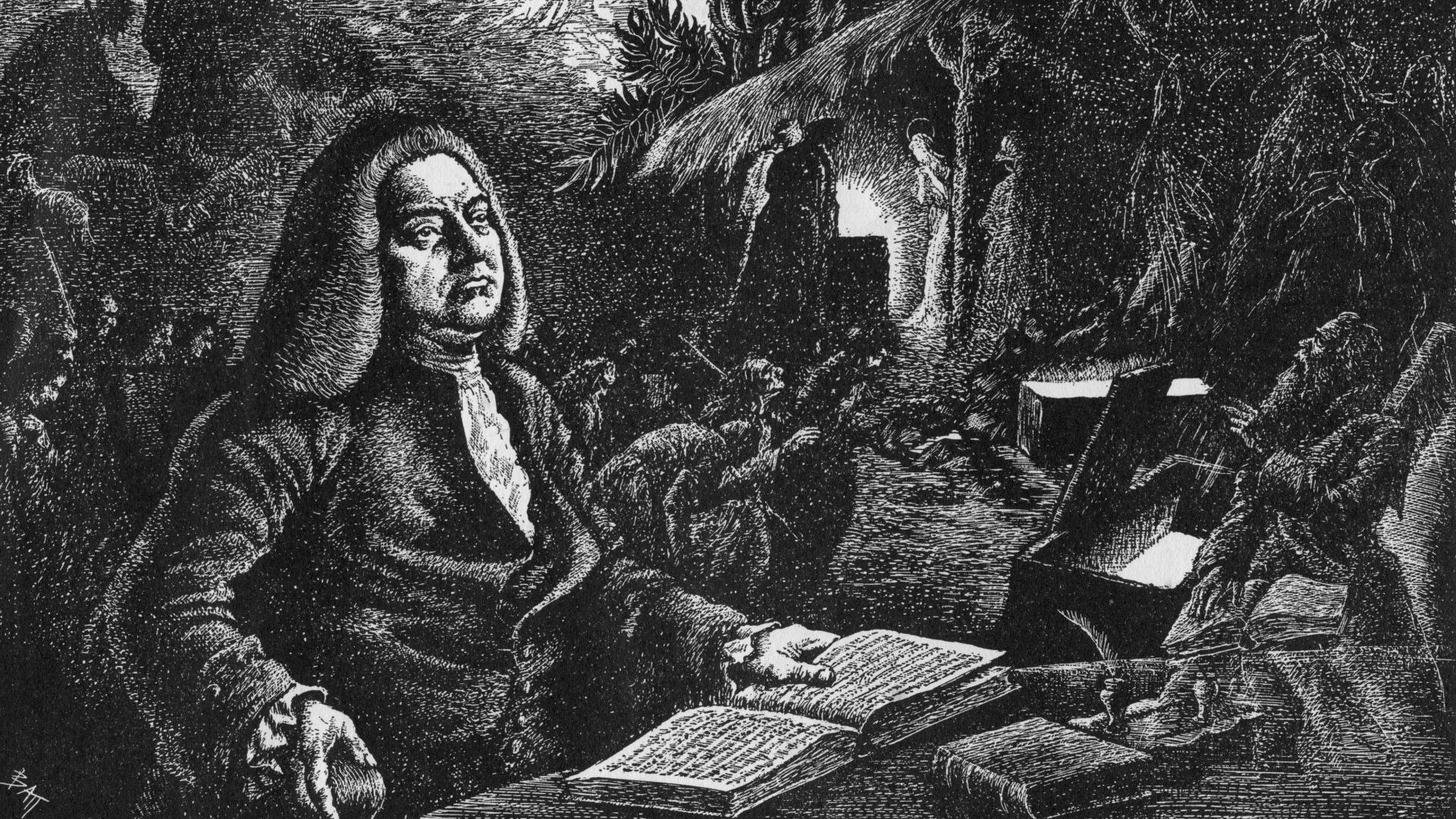

William Hogarth, a talent who enjoyed the adjectival tribute Hogarthian during his own lifetime, had a long and complex relationship with a number of European contemporaries who shaped his work more than has been acknowledged to date.

Their role in the artistic development of what many see as Britain’s all-time great satirist, the man behind Gin Lane – is brought to the fore in a fascinating new exhibition at London’s Tate Britain.

For a man who is oft seen as the progenitor of a new commercial model for cartooning, and singularly associated with social status in 18th century Britain, Hogarth’s artistic horizons were much broader than many may assume.

“London in the 18th century was highly cosmopolitan,” Tate Britain’s Alice Insley tell me. “Deeply connected with European cultural life and a centre for networks of trade and empire that spanned the globe.

“In the exhibition, Hogarth’s art is seen side-by-side with comparable pictures from other European cities, in ways that we hope will show those trans-European and global connections in the imagery artists used.”

Hogarth engaged with social politics head on. “Hogarthian” is used as a catch-all term for anything that honestly depicts social chaos with a clear-eyed honesty… undercut with a brutal humour.

But he was not alone. Other countries, too, had their Hogarths.

“Most prominently there’s the Dutch painter, Cornelis Troost, who was labelled the Dutch Hogarth in his own time. Hogarth’s art was a kind of well-known brand in the 18th century,” says Insley.

“There are plenty of artists in later times who self-consciously copied his art. But what the show will demonstrate is that artists in different national contexts had quite different takes on superficially very similar times – even Troost has a much more restrained, socially responsible approach than his English inspiration.

“Hogarth’s relationship with his peers on the continent was complicated – and British culture’s relationship with European culture was complicated too.”

Complicated is right. Britain was at odds with Europe throughout most of the 18th century, fighting against the French and Spanish during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), and alongside Austria (and their allies) in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48).

The age of the absolute monarch provided rich pickings for the satirist. “There are anti-foreign stereotypes in his pictures, we only have to look at the Frenchman being hoisted by his trousers in Beer Street to see that. But we also know he admired foreign artists and engravers, travelling to Paris looking to engage their services for the prints after Marriage A-la-Mode. Even in London he associated with many artists and cultural figures with European origins, such as the Swiss miniaturist André Rouquet or the French sculptor Roubiliac – he moved in an immensely cosmopolitan European scene.”

Marriage A-la-Mode, incidentally, is the title of a series of six Hogarth paintings illustrating the vanity and danger of marrying for money.

So, what do you think Hogarth would have made of Brexit? His painting The Gate of Calais (or O, The Roast Beef of Old England) seemed to have a handle on it, all those years ago.

“The Gate of Calais is one of his most direct and memorably antiFrench images. There is a lot going on in the picture though: he’s criticising the Catholic Church, with the figures of the fat friar and the superstitious fisherwomen, as well as the Jacobites, and presenting himself as a keen social observer, depicted with pencil and sketchbook in hand in the background. So it’s not just about hating foreigners, there is a critique of superstition and political disorder too. Hogarth painted this after a trip to France, where he was trying to engage the services of French artists he so admired, such as Chardin.”

Debauchery, avarice, poverty, social-climbing, xenophobia, an uncaring government, Hogarth recorded all this and more. Would it be fair to say that he was the first British artist to depict the actualities and realities of British life?

“He’s enormously important for the way he engaged with contemporary British life, with all its energy, chaos and danger. Hogarth conveys a sense of living likenesses in his portraiture, and a feeling for society’s manners and immorality in his subject pictures. What’s most important, though, is the way he created narratives out of this material.

“He was positioning himself as not just an observer, but as a social critic. It’s that positioning which is seminal and which still seems to resonate today.”

Reputations can stick, whether they’re true or not, and Hogarth is often held up as a rebellious figure.

“Hogarth was fiercely independent as an artist, earning a reputation as unique in his way. But he’s not quite the anti-establishment figure he’s sometimes taken to be.

“He long hankered after an official appointment, as sergeant painter to the king, and, later in life, he produced pro-government propaganda. If he was a brave social commentator, as he surely was, he was also one whose work appealed commercially.

“That drive towards commercial independence, above and beyond any political alignment, is what makes Hogarth a modern kind of artist.”

Hogarth clearly understood the plights of (and the opportunities for) the successful artist.

In 1734, he campaigned for artists’ rights to control how their work was used. The Engraving Copyright Act (also known as Hogarth’s Act) came into force the same year, protecting artists from others using their work without permission.

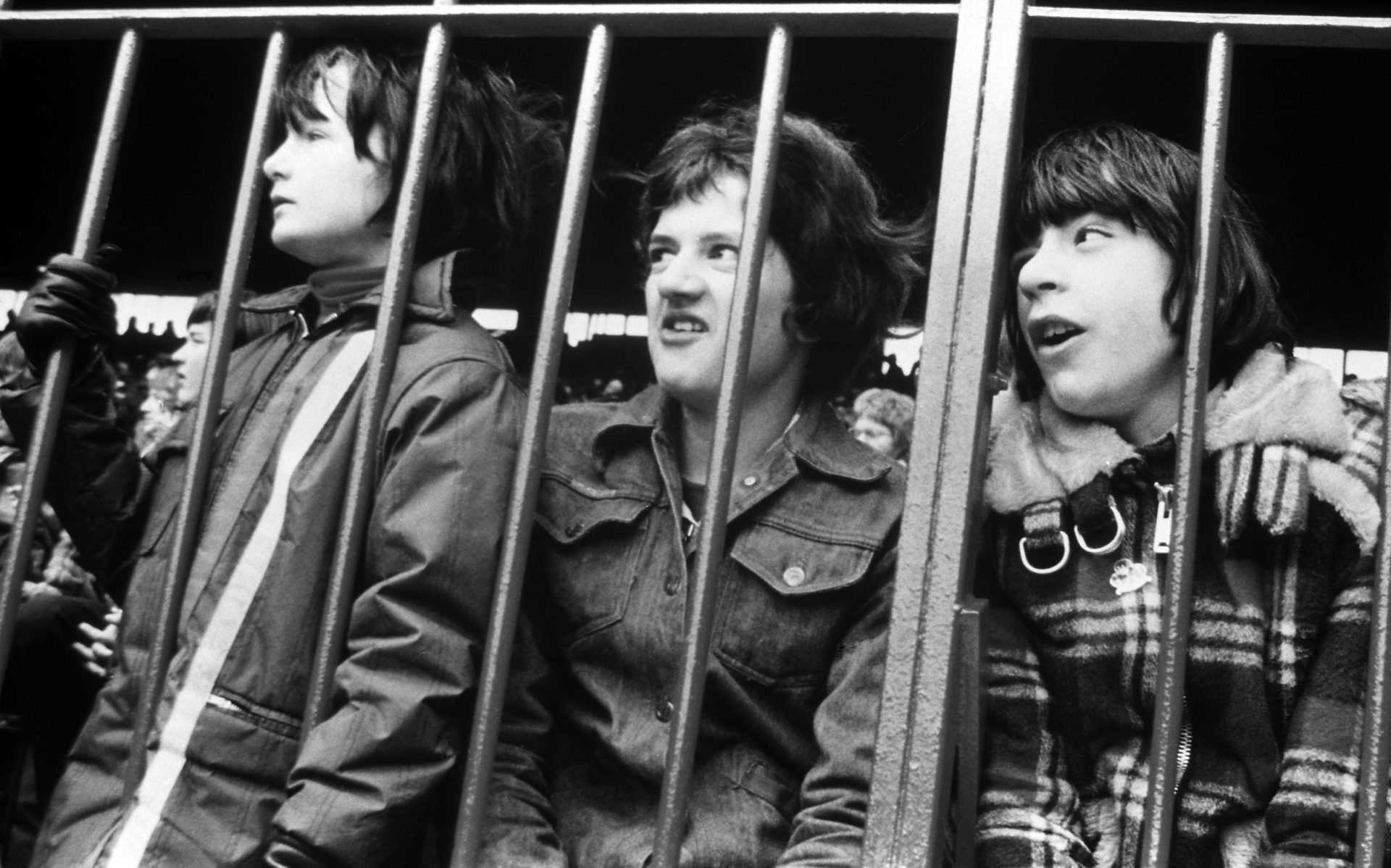

Hogarth is certainly due credit for his political actions, but is there anyone one can think of in modern society who reminds you of him? He seems to have had a certain – dare I say – punk rock defiance about him.

“The desire to use art to comment on society has endured and intensified during modern times. Hogarth has quite understandably been taken as a pioneer of socially engaged art.

“His art was not, though, particularly politically correct, even by the standards of his own times. Even if he could be satirical about the wealthy and powerful, he also punched down and could be cruel in his treatment of marginalised and vulnerable people. There are elements of profound sympathy for the poor and abused, but overall, you get the sense of an artist who looks at social change with a degree of anxiety and unease – I’m not sure that’s very ‘punk rock’. It’s not so clear cut.”

Maybe not punk rock, then. Or maybe punk rock as seen through a 20th-century lens. Perhaps Hogarth was a pragmatic impresario, a social satirist comfortable making cash from chaos.

Aside from his contribution to the narrative style and his innate pragmatism, how has William Hogarth’s legacy endured?

“He’s very much a product of his time – a time of rapid urban expansion, social change, economic development – when there was a lot to play for, and anxiety and destructiveness as well as positive change.

“Cartoonists have followed in his footsteps, as well as observational painters and portraitists, who develop his naturalism, and story-telling artists, such as Lubaina Himid, who explore narrative themes.

“But only Hogarth was the complete package.”

The Hogarth and Europe exhibition runs until March 20, 2022, at Tate Britain, in London.