I’ve an old friend who’s about as upright and law-abiding as it’s possible to imagine – she’s always worked, never claimed any benefits apart from child allowance (she was a single parent), and has no truck with febrile anti-establishment rhetoric. She also has a cousin – who she loves – who’s a high-ranking detective in the Met. Nonetheless, she has an implacable animus towards the police: so far as she’s concerned there’s no such thing as an impartial officer – her own family ties notwithstanding. The origins of this antipathy lie in an incident that occurred more than a decade ago, when her son – now a successful professional – was 12 years old. Driving in their car, close to their home, they were stopped by the police who subjected both of them to an extensive search – turning out pockets, frisking up against the wall etc – on the basis of nothing save a putative “suspicion”. The encounter lasted perhaps 20 minutes, but my friend was enraged and humiliated.

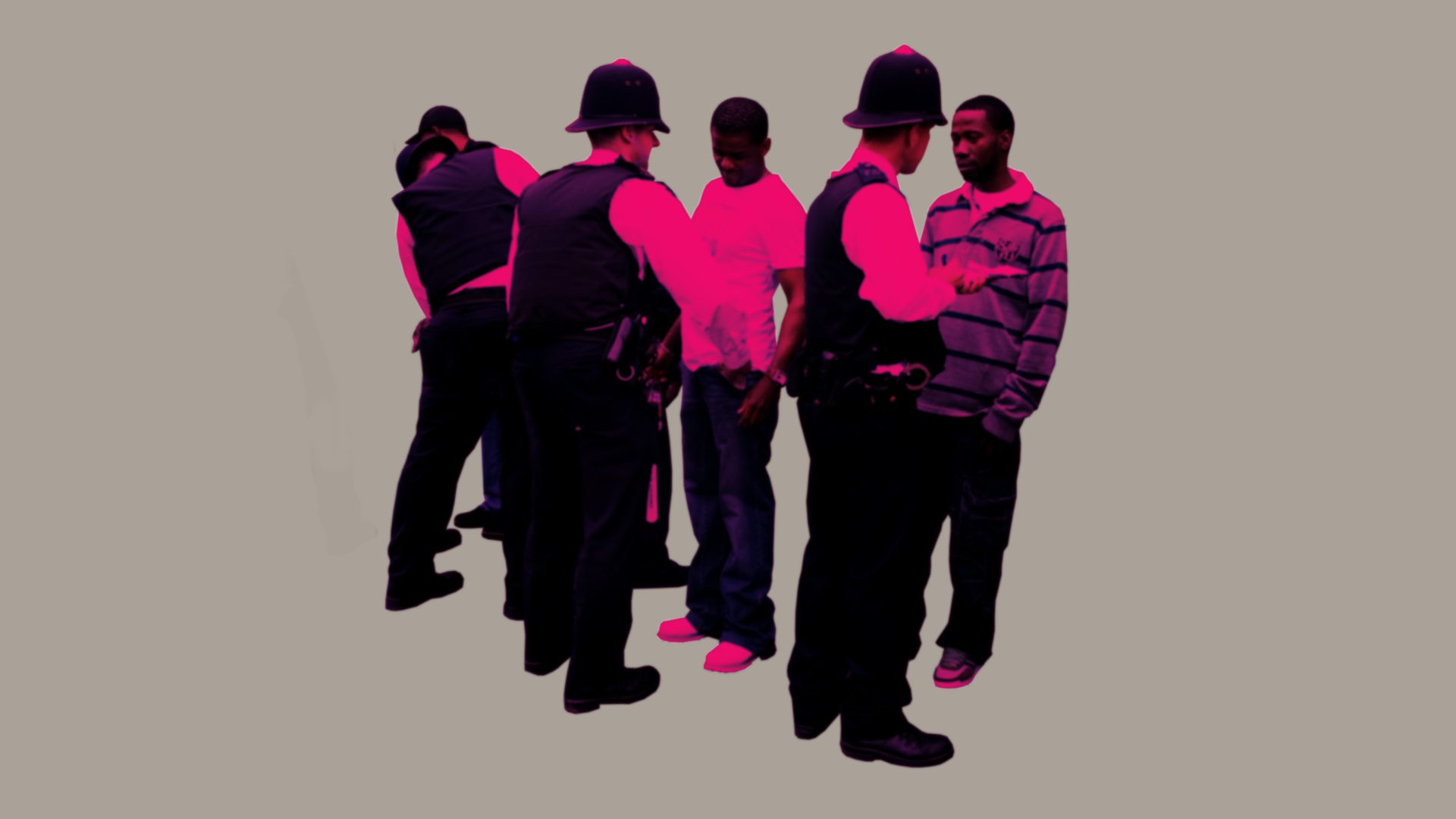

You have, of course, realised by now the scarcely suppressed premise of this “suspicion”: my friend and her son are black. As I say: this took place over ten years ago, when the numbers stopped and searched under suspicion of having committed an offence were at an all-time high: 1,179,746 people in England and Wales were accosted in this manner in 2010-11. Now, after a

steady decline over some seven years, this, the police’s seemingly favoured mode of public interaction, is on the rise again. Figures released last week show that in 2020- 21, 695,009 were stopped and searched – a 24% increase

on the previous year; while of these a hugely disproportionate number were from the black and Asian communities: black people are currently seven-and-a-half times more likely to be subjected to this procedure, Asians two-and-a-half times.

It hardly needs to be said that in the vast majority of these cases – as in my friend and her son’s – the police’s “suspicions” were entirely unfounded. Police forces’ leadership are well in advance of politicians when it comes to combating this iniquity, issuing directives to officers not to stop and search on the basis of “assumptions, stereotypes, and racial bias”. Sal Naseem, the police lead on discrimination, has also called for officers to police themselves, and intervene when colleagues act in discriminatory ways. This is all well and good, but probably largely ineffective while there’s a policy emanating from Downing Street of intensifying the practice, and relaxing the restrictions on police powers.

Setting to one side the arrant hypocrisy of the current incumbent – arguably primus inter pares when it comes to the nation’s criminals – laying down this particular law; there’s the resumption of a practice that historically has probably done more than anything else to alienate black and brown Britons from civil society: the Brixton riots of 1981 – which spread to other towns and cities with black communities – were directly caused by the indiscriminate use of such powers. Surely, the last thing the government should be doing now is taking an active role in creating another generation of disaffected people who only provisionally consent – if at all – to being

policed. (And under such circumstances it cannot but be marvelled at quite how law-abiding the generality remains.)

The white majority needs to ask itself what it can do to effect the necessary change. The answer is simple: if you see the police stopping and searching someone from the minority communities you should intervene and ask them what, precisely, is going on. This needs to be done with some discretion: a combination of politeness and firm authority works best, and if you can’t muster it don’t bother – but if you can, you should. I have a press card, which helps a lot – but even so there are some situations in which

I feel I’m unable to intervene.

One such occurred a couple of years ago when I was out walking with a friend at night. It was around 1am and we were close to the Tower of London in the City, when we saw a car had been pulled over by a police van and officers from the Met’s Territorial Support Group (the successor to the notorious Special Patrol Group) were searching it, while the black driver stood with his hands on the roof being patted down.

My friend – who’s not only white, but a university professor – went to intervene, but his manner wasn’t right, and he was simply told to “fuck off ” by an officer. As I was watching this unfold, a black woman who was walking

past came and spoke to me. “Why don’t you help your friend?” she said. “I would,” I replied, “but I’m worried I’ll be searched as well.” She looked at me calculatingly for a moment, before pronouncing: “I doubt it, mate.” And the

sorry truth is, she was probably right.