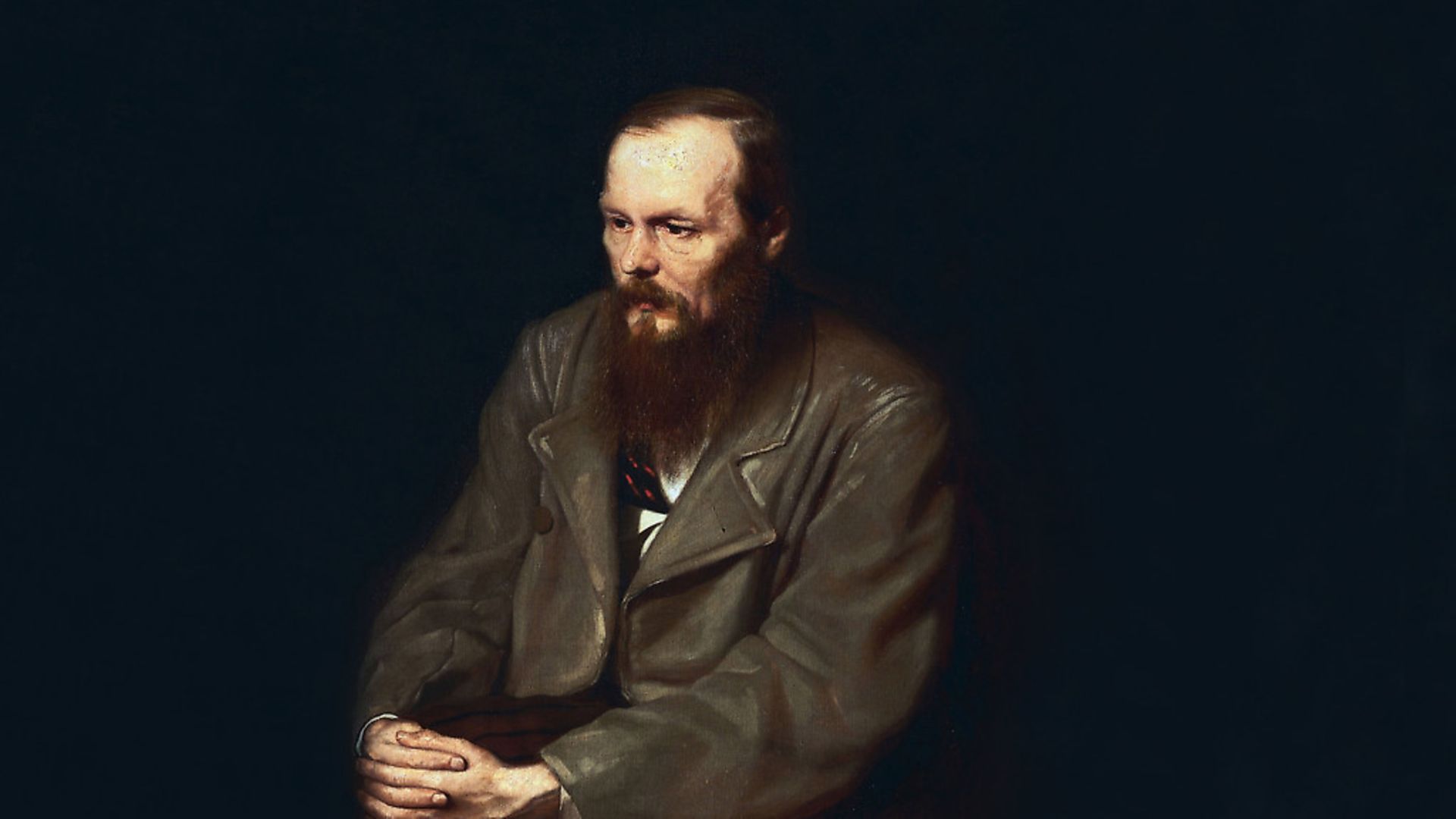

I once had a Russian student who I very much liked: an exile rather than an emigrant (he loathed Putin’s regime), he used to attend my literature sessions even though this wasn’t his subject. Sitting in on a class I taught on

Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, he was moved to write me an analysis of the different English translations of the novel that was in its way an exemplary exercise.

It used to be the case in Britain that if you had any aspirations to appearing cultured you needed to have “done the Russians”; by which it was meant that you had to have read the principal Russian writers of the 19th century: at the very least the novelists Tolstoy, Turgenev, Gogol and Dostoevsky, together with the poet Pushkin. It was widely understood that the crucible of the modern novel lay as much in St Petersburg and Moscow as London or Paris –

and the novel, as an artform, occupied a central position in European culture generally.

I dutifully did my required reading in my late teens and early 20s – although it was anything but a slog: in the translations of Constance Garnett and David Magarshack, the Russia of the past came beautifully alive to me, whether the glittering society balls at which Levin courted Anna, or the grotty furnished rooms in which Raskolnikov plotted his acte gratuit. Through the kaleidoscopic lenses of these great imaginations, I felt I was receiving fragmentary insights into an immensely complex and alien culture.

Following the invasion of Ukraine on February 24, media outlets scrambled experts on the Russian worldview to explain quite how insane Putin is, and how exactly his delusion is furnished. But while not doubting for a moment

that the Russian demagogue has – as we say in the requisite psy-jargon – inadequate reality testing (don’t we all?); I couldn’t help feeling that even a cursory reading of the Russians would have explained to many in the West both why he was going to do it – and a necessary although by no means sufficient condition of this: why he thought he could get away with it.

As a young reader of the august Russians, I wondered: why are even middle-class bureaucratic characters furnished with the title “general”? And why are there not only shabby-genteel but even impoverished ones who are still addressed as “princess” or “count”? Then there was the seemingly vast gulf between Europhiles and Slavophiles – and the vicious internecine conflicts it fomented; and the hysterical insistence everywhere and from everyone that

there existed a uniquely Russian soul – one that found its expression in the Orthodox communion and poetry. But if the world summoned by these texts seemed unfamiliar to begin with, as with all great literature: contextualisation and exposition went hand-in-hand, such that to understand which one of the Karamazov brothers was the parricide, was to know a great deal about the political and social convulsions of late 19th-century Russia.

And by extension early 21st-century Russia as well. So, I know that Russian nationalism goes deep and has a spiritual cast; I know that Putin’s evocation of a Russian imperial mission with a moral dimension (like that of any other hegemonic power), goes back not just to the early-modern era when Peter the Great organised all of Russian society along hierarchical, militarised lines (hence upwardly mobile generals and downwardly mobile royalty), but to the medieval one when the original Russian state arose in… Kyiv. And I knew before the invasion of Ukraine that the Russian sense of an abiding humiliation at the hands of powers to both the west and the east also goes back a lot further than the bombing of Belgrade in 1999, or the fall of the Berlin Wall a decade earlier.

My student’s report was not about the signified but the signifiers: by dissecting the way different translators handle idiomatic Russian he demonstrated to me the complexity and subtlety that make the language so

compellingly literary. With its vast vocabulary (it’s the only European language that has as much as English), and its almost synaesthetic way of introducing metaphor through tense rather than transposition, Russian – once explained even to a non-speaker – acquires a curiously stereoscopic

feel: no wonder so many of those fictional characters are given to plumbing the depths with their vatic pronouncements. Trying to comfort him when he

bemoaned his own deracination, I pointed out to my student that at least he was uprooted from a deep culture, not a shallow one – but this didn’t comfort him much.

And why would it: because he undoubtedly understood that if it came to war, the Russian people would be difficult to detach from a culturally induced self-conception that unites them with Putin. So, it seems reasonable to conclude that if only Biden, Johnson, Macron, Scholz et al had done the Russians, perhaps the Ukrainians might not now be being done by them.