Whatever happened to the Kafkaesque? 2022 was a good year for Proustians: the centenary of the writer’s life has been the occasion for a slew of exhibitions and a widespread reappraisal of his oeuvre. Joyceans have also received their due, as the 100 years since the first edition of Ulysses was marked in the time-honoured way of all such celebrations: a lot of people committed to reading the famously intractable novel – few completed the task. But this is to conflate nounal and adjectival forms – the truth is, not even the most pretentious among us refer to our epiphanic recollections as Proustian; while to confer Joycean on anything is to immediately pose the question – much in the way the intractable novel does itself – what exactly does that mean?

But the time was when people really did say quite a lot of things were Kafkaesque quite a lot of the time. Why? And more to the point: why have they stopped? Have any number of situations, scaled all the way up from the personal to the political, simply ceased to manifest that numinous – yet absolutely distinctive – quality we associate with Kafka’s writings? Or is it, rather, that for all the accessibility of those writings – certainly as compared with those of his fellow modernists, Proust and Joyce – there’s no longer the critical mass of actual Kafka readers required to keep the ascription in circulation?

There still are plenty of people who know about Gregor Samsa awakening one morning from unquiet dreams to discover that during the night he has turned into an enormous and verminous insect – but they know about it in the same way they know about Dorian Gray’s magically youthinducing portrayal: it’s become a modern myth, a hazy collective memory of a time when literary creations – and the perspectives they engender – were an integral part of cultural discourse.

Besides, it isn’t Gregor’s transmogrification that’s most representatively Kafkaesque about the novella – it’s the belatedness of his realisation of the fact: we feel certain that if he’d grasped what was happening during the night he would have taken steps to avert it – just as we have the equally queasy conviction that were Josef K to have paid adequate attention to the people who “must have been telling lies” about him, he wouldn’t have been arrested, subjected to a lengthy and unjust trial – then summarily executed.

Kafka’s post-traumatic protagonists are too late to take control of their destinies – and moreover: they always were. Their entire mental content – exhaustively elaborated over scores and hundreds of pages – is at once vacillatory and self-recriminatory, as the dreadful dithering that dances attendance upon even the dullest of our deliberations gives way, yet again, to the despairing acknowledgement that it really wouldn’t have made much difference if we’d done the opposite anyway. Even with the most acute awareness we’d still have ended up as a smear of brown crud to be swept up and disposed of by the cleaner – or apathetically regarding the knife being wielded by our assassins, so doing their dirty job for them.

If the stoic position is to regard our sense of free and effective agency as the user-illusion generated when what we want happens to coincide with what’s necessitated for us; then Kafka’s is to undermine the illusion so relentlessly that it becomes unsustainable. And – contra contemporary so-called soothsayers – he never sugars the pill with anything Panglossian: “There is infinite hope, but not for us” reads one of The Zürau Aphorisms, composed in the weeks immediately after he realised he had tuberculosis – at that time a progressive, incurable and fatal disease.

Posthumously repurposed by his friend and amanuensis, Max Brod, as some sort of saintly figure, the rise of the Kafkaesque in the decades straddling the second world war was a curious inversion of the writer’s own law of negatively eternal recurrence.

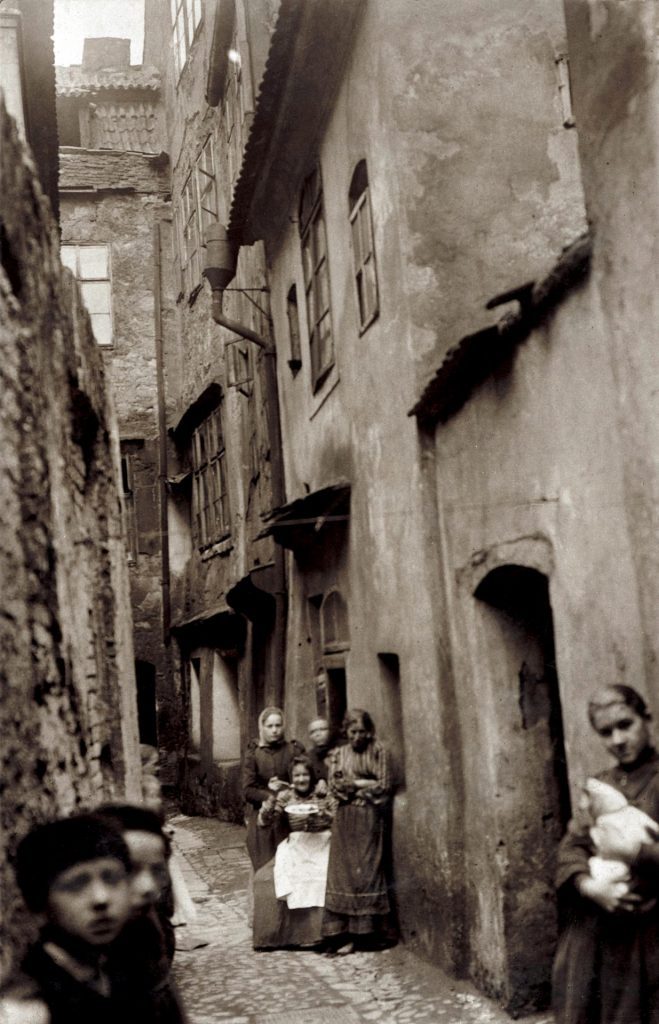

By which I mean to say, it was all about good timing: initially translated into English by the Scots husband-and-wife team, Edwin and Willa Muir, the stories, together with the three unfinished novels that Brod saved from the destruction Kafka had mandated on his deathbed, entered collective political consciousness at precisely the point where such an explanation was required. After successive regimes of declining legitimacy, the writer’s own homeland transferred straight from one totalitarian regime to another – an uncanny (in German, unheimlich, literally “un-homelike”) predicament. One that in the late 1940s and early 1950s was felt not just by those now trapped behind the Iron Curtain – but also those in the West who had exchanged the massively expanded bureaucracies required to wage total war for those deemed essential to pay everyone a burgeoning wage.

That Brod’s saintly Kafka was dead by 1924, before the rise of the exterminatory Nazis, made him an obvious candidate for a prophet’s mantle. The Nazis’ genocide in Prague – wholly eliminating the Jewish community to which the writer had belonged – was an additional factor: once such vatic pronouncements would’ve been ex cathedra, but emerging now from the charnel house of the 20th century were ones wholly ex nihilo, since their obscure creator was now doubly effaced by his own demise and that of the very culture that had sustained him. Moreover, if they were read rightly, didn’t his works reiterate over and over this terrible warning: stay alert, lest you succumb to the hideous transformation – whether it be of your own body, or the body politic? It’s an interpretation of Kafka that has paradoxical staying power: because each new debunking of the revelation cannot help but aspire at the same time to replace its priestly author with a more authentic portrait.

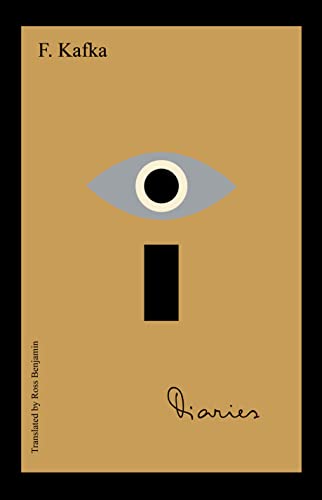

The latest iteration of this comes with a new translation of Kafka’s Diaries – another of the literary properties Brod rescued from oblivion, and edited so as to burnish his iconic conception of his friend. It’s certainly true that Brod’s version of the diaries – which was the one translated and available heretofore in English – was bowdlerised; the emendations and alterations intended as much to present a portrait of a preternaturally fluent writer – even in this necessarily staccato form – as one whose personal conduct was exemplary. The new translator, Ross Benjamin, gives us a sketchier Kafka, both morally and artistically: a Kafka who misspells, and tries out numerous formulations of a paragraph on the page – and a Kafka who observes prostitutes in a brothel with the same objectivity (the eye that looks out pitilessly, does so inwardly as well), as he does the genitals of a man he shares a steam bath with.

But, unfortunately, the established sanctity of Kafka is too great for these revelations of a more earthily imperfect (and homoerotic) individual to have any impact. What the Czech writer Milan Kundera terms “Kafkaology” – the doxa of the writer’s cult – will only absorb these new revelations and add them to its storehouse of pseudo-wisdom. Once a writer achieves this sort of status – as Benjamin’s introduction to his translation amply demonstrates – even his errors are offered as evidence of his, um, inerrancy.

Brod’s own Zionism, and the chequered history of the literary trove he both saved and bowdlerised, fused Kafka’s fate for a while with that of the survivors – as if the posthumous recognition of his works was somehow at one with the belated recognition of the Holocaust, and by this fact alone were spreading salve on this awful wound. Brod took the trove to Israel; and that the Zionist state itself should become caught up in its fate – and by extension, its interpretation – only seems (for those inclined to such magical thinking) further proof of the prophetic nature of the Kafkaesque.

But as I say: the numinous quality of the writing has nothing to do with the holy haziness of premonition – and besides, unless you actually believe in the possibility of prescience, why would you ascribe it to a secular Jew any more than to a superhuman one? Kafka wrote about the human predicament under the condition of modernity – understanding by that an inexorable integration of the human subject and its ineffable subjectivity into the objective and quantifiable realm of the machine: Gregor’s fate is sealed not because he didn’t register his nocturnal metamorphosis, but because he slept through the alarm and failed to enter the regimented temporal zone demanded by mass and mechanised production. (Recall: he’s a travelling salesman – that most rigidly timetabled of occupations. I know – I’ve done it.) But whether it’s the case that Gregor is actually an invertebrate or merely too spineless to show up for work, we never ultimately know.

The sense of an implacable process humming away beneath the conduct of human affairs is everywhere Kafka – The Castle, perhaps his greatest work, is an evocation of a bureaucracy so reliably arbitrary that all its actions have the nightmarish character of a computer with the temerity to say “no”, combined with the whimsicality of one singing “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do…” But lest you think me half-crazy, let me reassure you: I don’t think Kafka anticipated the rise of artificial intelligence any more than he did that of Nazism or Stalinism. He did, however, work as a lawyer specialising in claims assessment for a state-backed insurance company – and this put him at the exact interface between the deterministic clarity we expect of machines, and our own ever-opaque fates.

Until, that is, it’s too late. The mid-century western workers who looked eastwards pityingly, seeing there political systems the very acme of alienation – were awakened by their own children to this ugly reality: they had sold their own souls on the instalment plan, making regular repayments for a durable sense of insatiability; for there’s always something new out there to buy. The Kafkaesque was expressed by the monumental contradictions of the mid-century totalitarian regimes, precisely because they were such startling manifestations of the repressions all civilisations demand of their human components – ones that become more exigent the more those components can be standardised.

The cybernetics of the contemporary era has been in place for a while now – if by the term “cybernetic” is understood those systems that depend for their effectiveness on the integration of human and machine.

Indeed, Isaac Newton, an originator of both the sort of actuarial tables employed by insurance companies and the differential calculus necessary to mechanically integrate variable rates of change, stands as the first great cybernetician – while the very term “cybernetic” is fading out of existence, together with the Kafkaesque, not because of the looming approach of human consciousness’s supersession by artificial intelligence, but because our lives have now been so comprehensively quantified, and so completely integrated with malfunctioning machines and mechanistic processes, that we can no longer see through the translucent screens of this terminally frustrating realm.

Once upon a time encounters with human bureaucrats were the point at which the superficially free – but in reality, tightly constrained – nature of our lives was most sickeningly revealed. And just as we thought the bureaucracy was useless, except as a weaponisation of our own ennui to control us, we also thought them “faceless” – because we knew perfectly well that’s how they were condemned to see us. So, we sat there for decades, each staring into each other’s dull eyes, marvelling at one another’s singular stereotypy. And then both parties would get up, shuffle together their respective sheaves of largely superfluous – but for all that essential – paperwork, and quit the shabby little office, muttering under their breath about how very Kafkaesque this encounter had been.

But now we’ve cut out the economically inefficient middlemen and women, and instead confronted ourselves in our myriad mirroring screens with the repressed rage of a billion Calibans. We have incorporated the Kafkaesque so completely into our lives – becoming both faceless bureaucrat and faceless citizen (or comrade, or subject) in one individual – that we’re no longer able to recognise it, and hence name it. After spending seven hours on the chat function of the British Gas website, trying to explain – first to algorithm-powered bots, then to underpaid humans in call centres half a world away – that I am unable to access their website, and hence pay their bill, I am too exhausted to even sigh “Kafkaesque”. Moreover: how can such a world-girdling system of communication and commerce make me feel so very… claustrophobic.

The only reason I want to pay the bloody British Gas bill (I’ve left the property it’s for), is because I don’t want them to hand it on to a credit control agency. Of course, they’ll probably harass me online for quite a while before they actually send the boys in. But when those boys do arrive, I feel pretty certain they’ll be like the ones who hustle poor Josef K on the patch of waste ground where he complies impotently as they stab him to death. Poor K – his semi-synonymous creator tells us: “He was not able to show his full worth, was not able to take all the work from the official bodies, he lacked the rest of the strength he needed and this final shortcoming was the fault of whoever had denied it to him.”

And yes: that’s us, killing ourselves softly with the Kafkaesque task of taking on all the work of the official bodies.

Ross Benjamin’s new translation of The Diaries of Franz Kafka will be published by Penguin Random House in January