It wasn’t the djellaba, because I wasn’t wearing one – it being too warm now – only a thobe and a rain poncho. Still, the conversation quickly became warm – then animated, before my interlocutor told me their story.

Not, of course, in its entirety – we were in a post office queue; but still, a fair bit of it: we were in a post office queue. Indeed, post office queues are often good for finding out about people’s lives – there’s the time factor, obviously; but also, I feel, it’s still this strange sense of being in the presence of artefacts that – while we ourselves may remain static, on a rainy day in the south London suburbs – will soon be winging their way to quite other places.

And while, granted, many of these will be surpassing mundane (not least because a considerable number of those queuing for counter service rather than using the automated postage machines, or the drop-off facility, will be small-scale web vendors of one sort or another, often still taping and tying some unwieldy parcels as others are getting awkwardly weighed, franked and despatched), there’s still a pervasive ambience of exoticism. One heightened by the awareness that many present will be thinking of homes either long since left behind, or recently departed from – while experiencing once again the tearing sensation as the hooks of there loop into the heartstrings of here, and deliver a savage little yank.

Undoubtedly, he felt this – but more proximately, it was the queue, the inefficient Ebayers, and the general air of deshabille that bothered him. He’d been speaking Arabic into his phone, but we got talking in a mixture of English and French, because I’d already suspected he was a Berber, but my Tamazight ain’t what it used to be. The Brixton post office was, he kvetched, awful – the queues longer than anywhere else in London, the staff more lackadaisical, the customers… Well! At this point, he gestured wildly about him at my fellow Brixtonians.

True, many of us take our time over transactions and are given to whimsical extempore conversations, often conducted loudly in patois so impenetrable that only the occasional “seen”, “wh’appen?” or “ras-claat!” can be made out by non-natives, but I nonetheless felt something akin to indigestion stirring inside me as he continued; a feeling I later realised was patriotic pride. Anyway, we spoke of Fez, and Meknes, and Casa – where he was from. He kept on darting looks out of the door to where his moped was parked on a yellow line: “I can’t afford a ticket,” he said, “it’s 80 quid…”

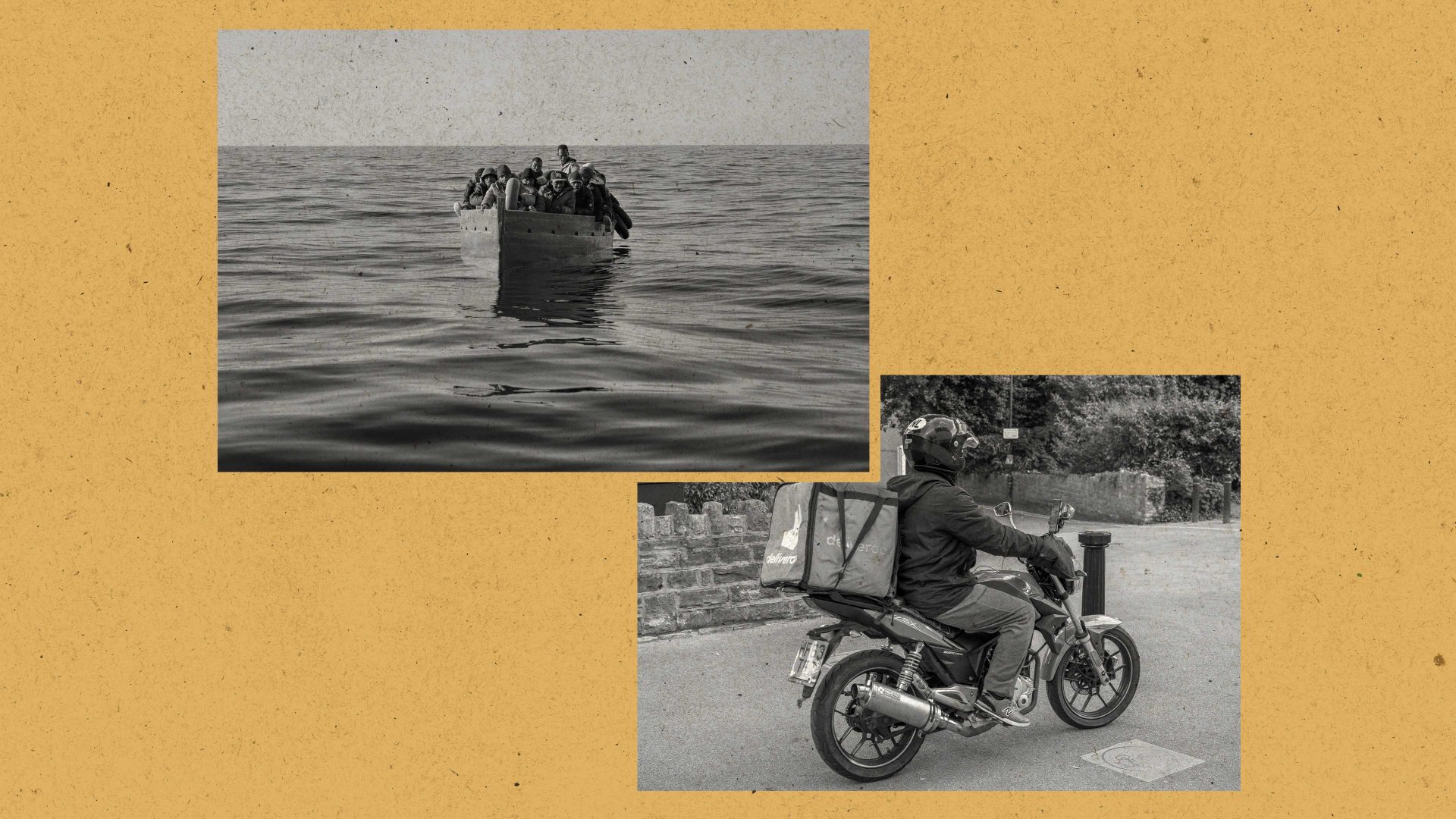

Then it all tumbled out: he had crossed six years ago from near Cape Spartel in an open boat: he wasn’t scared – his father had been a fisherman, but he’d got ill and died. So, his teenage son went to Barcelona to make the money to send back to support his mother and younger siblings. He liked Barcelona – and the people were, on the whole, friendly. Indeed, so accommodating that he was able to acquire papers in a couple of years. But he couldn’t earn enough money – so he came here.

Where, in nine months, he had become fluent in English and acquired a pukka-looking biometric residence permit, which he flashed at me, with justifiable pride in his own smarts. As for work – you guessed it: he’s the guy delivering your guilty-pleasure, late-night fast food. And no doubt delivering it to plenty of people who, if told about him, and where to find him, wouldn’t hesitate to rat him out to Border Force, so they could cuff him at dawn and throw him on a flight to Kigali; but then that’s the essential point: if they were told about him.

If they’d met and spoken to him – if they’d apprehended who he was, and the struggles he’d undertaken so he and his family could survive – then, with the exception of screaming bigots and sociopaths, I suspect they’d have been as disarmed by him as I was. Certainly, no decent person could begrudge him the £380 with which he was supporting a family of five – and yes, that’s net: he certainly begrudged the taxes, but he was – being a decent person himself – paying them.

So, a young man who understands the certainties of life rather better than many. What was his own dream? I asked him, since we’d moved so rapidly from chitchat to confidences. A fisherman, he replied unhesitatingly, “like my dad”. Let’s hope there are still fish off the coast of Morocco once he makes it back there. Or, indeed, off the coasts of Britain, if he elects to stay here.