A bad blue paint job in a strange, age-of-Covid guesthouse in Falmouth – (online booking, no staff – just keypads for entry: a ghost hostelry), unleashes late at night this chain of associations in a tired traveller: ‘blue… a colour so cruel…’ But of course, along with automated lodgings come the internet, so this Madeleine moment bodies forth into a YouTube video of Roland Gift and the Fine Young Cannibals warbling away some 35 years ago. Gift is in pleated high-waisted trousers and sweat-stained white shirt; behind him David Steele and Andy Cox, the two other founder members of the group stand, hunched and strumming their guitars in that micro-chopped manner they evolved as The Beat, one of the so-called ‘two-tone’ bands (mixed black and white) involved in the ska revival of the early 1980s.

It was always a surprise to hear Gift performing, because he was so softly spoken and self-effacing in person. He’d come to the meetings of the small housing co-op we both belonged to – but seldom said anything. Mutual friends told me he was rehearsing with a new band, but I didn’t make much of it: in the Camden Town of the mid-1980s everyone seemed to be either in a band, or on the fringes of one. Other members of the co-op belonged to 23 Skidoo – an offshoot of Genesis P-Orridge’s band-cum-avant-garde-cult Psychic TV – and it was darkly rumoured that part of their gig consisted in masturbating and then sending tissues crusted with their emissions to Orridge, together with written accounts of the fantasies that had engendered them. Still others were hanging round a determinedly drunken Irish outfit called Pogue Mahone: ‘Kiss my arse’ in Gaelic. So when Gift suddenly appeared on Top of the Pops I was a little surprised – but not much. Given the Gift treatment, Blue – a diatribe against the Thatcher government of the time – became a tearful lament, and this led me on, in my cruelly-decorated room, to a series of performances exemplifying this ultra-sweet side to Jamaican popular music. I found myself watching Ken Boothe as he sang (or rather, mimed) his big mid-seventies hit, Everything I Own, also on TOTP. This, in turn, led me to deeper reflections on the symbiotic relationship between white British audiences and African-Caribbean performers. Trinidadian Calypso stars of the 1940s and 50s found enthusiastic audiences here, even if initially these were viewed as ‘novelty’ acts. Ska, rocksteady, and then reggae musicians all charted in Britain throughout the 1960s and 70s. Somewhat paradoxically, the racist skinhead subculture cleaved to the bouncy beat of the music – and Skinhead Moonstomp, by Symarip (whose members were of African-Caribbean heritage), became their anthem. Other ska singles were also calculated to get them on to the dance floor and kicking up their bovver boots – boots that later that night might well be being planted in black and brown faces.

Hegel proposed the master-slave dialectic as a way of understanding social and cultural development. Struck by the way that the enslaved Greeks nonetheless became the intellectual and aesthetic tastemakers of the Roman empire – to the extent that Patrician Romans spoke and wrote more in Greek than Latin – he proposed this universal law: inasmuch as the master dominates the slave, the slave also dominates the master – because without a slave he has nobody to reflect back at him his own mastery. In time, the slave will exploit this pivot in the status quo – and arguably, the effects of this phenomenon are all around us now: in the US, where the audience for African-American rap music (and hip-hop culture more generally) is overwhelmingly white and affluent, and of course here in Britain.

The depredations and atrocities committed by the British plantation owners throughout the Caribbean were legion, but it’s in Jamaica that the most extensive and evolved system of exploiting the enslaved was developed. I suspect Hegel – if he were prone to a little skanking – might well argue that it’s precisely the depth of the suffering that black Jamaicans endured that makes their culture in particular quite so salient in contemporary Britain.

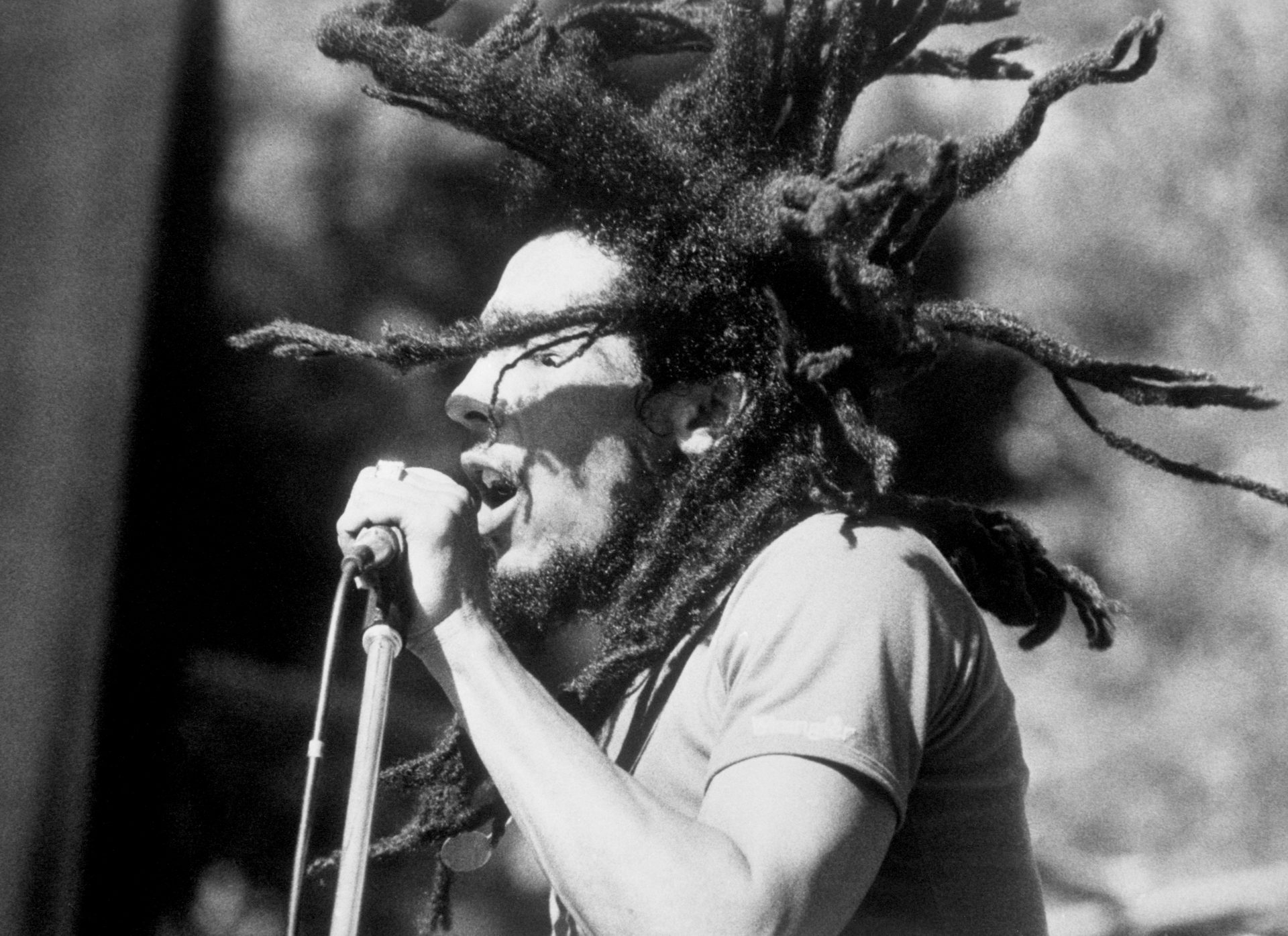

When, as white youths, we danced to reggae and ska in the early 1980s we thought we were entering into an entirely progressive trajectory: the arrow of history climbing ever higher and higher, a harbinger of cultural inclusiveness for all minorities. But leaving the cruel room the following morning, and walking along Market Street in Falmouth, I was arrested by the sight of a portly, inebriated figure, slumped in a doorway with a guitar and soliciting change with his own execrable version of Bob Marley’s Redemption Song. A fountain of matted dreadlocks cascaded down over his face – a face that was indeed a whiter shade of pale.