On the last Saturday before America’s election day, Fox News’s Bret Baier declared Pennsylvania “the centre of the universe.”

In 2016, Donald Trump had won this vast swathe of the so-called Rust Belt by a whisker. In 2020, playing on his credentials as the champion of the average working American, Joe Biden won it back.

We now know that Trump was about to retake the “Keystone State”, and with it the White House. But why? What was driving Pennsylvania to make its decision, with all its implications for the future?

By that Saturday night, to try to find out, I was coming to the end of a journey through Pennsylvania’s recent past.

In the wake of the second world war, America’s economy was booming, just like its birth rate, and all those new parents needed affordable homes. A company called Levitt & Sons pioneered a way of mass-producing homes at incredible speed – and in Bucks County on the outskirts of Philadelphia, a whole new “Levittown” sprang up to house the workers streaming in to work in the local steel plants.

Wandering its cul-de-sacs today, many of the original houses have been replaced, but the 1950s dream of suburban mass prosperity is still visible. For decades, this living monument to that hopeful postwar world backed Democrats for the White House. Not now. Everywhere I went, the lawns were adorned with Trump signs.

But why? Outside one of the surviving original homes, a young man called Shawn told me his grandparents had lived there since the 1950s; with their passing, his mom had inherited the house. He was going to vote for Trump.

“I don’t necessarily like him as a person,” he told me, but everyone needed “cheaper gas”. Some of the Trump signs simply read ‘TRUMP LOW PRICES, KAMALA HIGH PRICES’.

The Bucks County Herald detected similar sentiments: that the Democrats no longer cared about working people; that Trump, no matter his personal failings, seemed to have their interests at heart. It wasn’t far from here that the once-and-future-president popped up in an apron, serving fries at a McDonald’s.

One of the journalists covering that photo-op was Peg Quann, who has reported on the county for many years. She told me she “could not imagine another president in my lifetime doing that”.

Fifty miles north-west of Levittown is Northampton County, one of the most swing-prone in the state, and once home to a powerhouse of American industry. In the city of Bethlehem, alongside its mighty blast furnace, stood the headquarters of Bethlehem Steel; the company’s girders built such emblems of the American 20th century success story as the Golden Gate Bridge and the Empire State Building.

Today, Bethlehem’s vast steelworks is a rusting hulk; beside it is a casino, built by the late Republican megadonor Sheldon Adelson. You could hardly ask for a more pointed symbol of how the economy has been transformed.

Dismissing places like this the Rust Belt is too simple: Bethlehem and the nearby city of Easton have revived by pivoting to the hospitality industry – restaurants, tourism, festivals, concerts. Opposite the old blast furnace is a new ArtsQuest Center.

And since Covid, distribution warehouses have become a new source of rural jobs. But they do not pay well.

Professor John Kincaid is a scholar of state and local government at Easton’s Lafayette College; as he puts it, the memory of steel work persists. And so: “when Trump says, ‘I’m going to bring your jobs back, I’m going to bring industry back,’ they buy that.” Though Kincaid doubts that Trump can actually deliver.

Up the hill from the dead steelworks, Bethlehem rapidly grows leafier. At Lehigh University, I met Dr Ben Felzer, a climate scientist, and chair of the city’s Democratic Committee. He too reports talk of high prices, and “this weird feeling that things were better under Trump”.

He and his fellow campaigners counter that much of this was shaped by the impact of Covid, that America has “the strongest economy in the world right now,” that Trump’s policies will make things worse. When I tell him about Shawn in Levittown backing Trump for cheaper gas, he cries: “Gas is cheap now!”

One major issue, he says, is the lack of affordable housing; Harris was offering to help with costs – so perhaps a new Levittown would restore that post-war sense that ordinary people’s lives were at the core of politicians’ concerns. But the chances of getting such a development past Bethlehem’s strong preservationist tendency seem low.

If Trump has been pitching his appeal to America’s workers – so has Biden, dedicating vast sums to building infrastructure and developing clean energy technologies, while being the most pointedly pro-union president in decades. For some, this has buried the sad memories of steel.

In Pennsylvania’s far west on the Ohio River lies Beaver County. Here, old works have been torn down, leaving the sites clear for fresh industrial development. In their new Union Hall in the city of Beaver, business agent Larry Nelson and organiser Ed Gerber of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers’ Local 712 sounded strikingly optimistic about the local economy, and their members’ role in it.

The demand for chip plants, data centres and industrial solar complexes is generating more work than they can handle; Nelson predicted that “in the next year or two, the work is going to double here”. Unless, he said, Trump won.

Gerber told me they were ready to work with any politician that values unions, but he was not impressed by the Republicans’ recent rhetorical turn towards workers – nor by Trump’s performance at McDonald’s. That final Saturday, they were busy organising a union-member-to-union-member door-knocking campaign – but Gerber worried that, overall, the Democrats had “not done a good enough job” of talking to people, particularly those with socially conservative views, “on a level ground”. For all the new jobs, even Beaver County was no Democrat shoo-in.

Which party could convince ordinary working Americans it was on their side? That night, in Pittsburgh, I saw a Harris ad fronted by a steelworker, attacking Trump for cutting billionaires’ taxes, promising Harris would “end price gouging”. On a downtown billboard, adverts paid for by the Democratic National Committee sounded strikingly pro-union messages: “Billionaires Didn’t Build the Middle Class. Unions Did.” And “Project 2025 Would Gut Unions. Don’t Pick the Scab.”

Next day, the city was preparing to host rallies by both candidates. Harris held hers at Carrie Furnaces – a former steelworks. But given her campaign’s heavy emphasis on protecting abortion rights, and democracy itself, could this turn in her messaging trump Trump’s relentless stress on jobs and prices?

Come Tuesday night, it soon became clear that Trump had won Bucks County, and Northampton County, and Beaver County. And with them, Pennsylvania. And with Pennsylvania, the presidency.

In Bucks, Peg Quann thinks “The silent majority had spoken, and he stooped to conquer.” Trump, she reflects, was “typecast as the flawed candidate who supported the wealthy, but when he cooked fries at McDonald’s – asking the staff about their jobs, and climbed into the trash truck – he spoke to Bucks County’s families of all economic levels.”

Family values, the need for affordable housing and the impact of illegal migration on the county’s drug problems appeared to have overridden Harris’s appeal on abortion.

In Northampton County, John Kincaid was startled not by Trump’s victory, but by its size. “He really built a multi-ethnic working-class coalition, quite surprising and unexpected…what the Harris campaign failed to really zero in on is that the race was primarily about the price of eggs, not Trump’s character.”

Ben Felzer lamented that even in a county with five institutes of higher education, Harris couldn’t win. He fears the consequences will be calamitous, both for American democracy, and because now the last chance to avoid “the worst path towards climate change” is lost.

In Beaver County, Larry Nelson worried about the fate of Ukraine and for the future of Biden’s investment in good jobs. Ed Gerber thinks Trump’s lead was underestimated “due to a failure to realise how out of touch [the Democrats’] message has become with working-class people. Fear and lies are a more effective message than facts. Feeling matters more than truth. Tapping into people’s fears of “The Other” has always been an effective way to gain power.”

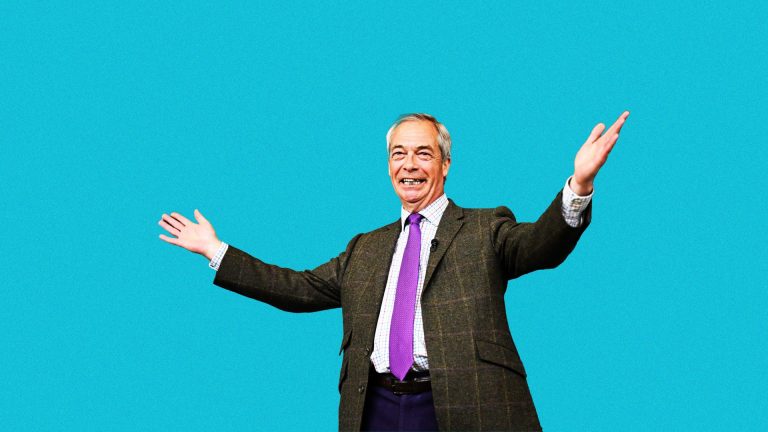

For a British visitor, it is both astonishing and eerily familiar to see how the Democrats have lost touch with what was once their “base” in a state like Pennsylvania. Losing the trust of so many working people in these places – to Donald Trump, of all people – is a failure that has been coming for a long time.

It may be that only by combing back through the past can Democrats identify the points where the splits occurred, and so work out how to repair them. For now, much depends on whether Trump can make good on his grand promises to put the American worker, in Pennsylvania and beyond, at the centre of the universe.

For Ed Gerber, meanwhile, the outlook is dark. He is scared that Trump “has an unobstructed path to tyranny”. But, he says: “I want the world to know that there are a lot of us that are ready to fight.”

Phil Tinline is the author of The Death of Consensus: 100 Years of British Political Nightmares. His next book, Ghosts of Iron Mountain, about American political nightmares, will be published in March.