Linguicism means discrimination against people on the grounds of their language, dialect or accent. Linguistic scientists are quite naturally opposed to this, and are agreed that terms like “wrong” and “inferior” have no part to play in objective discussions of languages.

After all, what could it possibly mean to say that a way of speaking is “wrong”? How can a vowel system be “incorrect”? In what way can grammatical structures, as used naturally by native speakers, possibly be “wrong”?

The title of the novel Eating People Is Wrong by Malcolm Bradbury reminds us that there are different types of “wrong”. There is the kind of wrong in which Lisbon is the capital of Spain, or 3 multiplied by 3 equals 8. As the Oxford English Dictionary says, these statements are wrong in the sense that they are “not in consonance with facts or truth; incorrect, false, mistaken”.

A second type of wrong is what we can describe as “the hitting-someone-on-the-head-and-stealing-their-money” kind of wrong. This is wrong in the OED sense of “deviating from equity, justice, or goodness; not morally right or equitable; unjust, perverse”. Eating people is presumably this second kind of wrong, though I suppose worse.

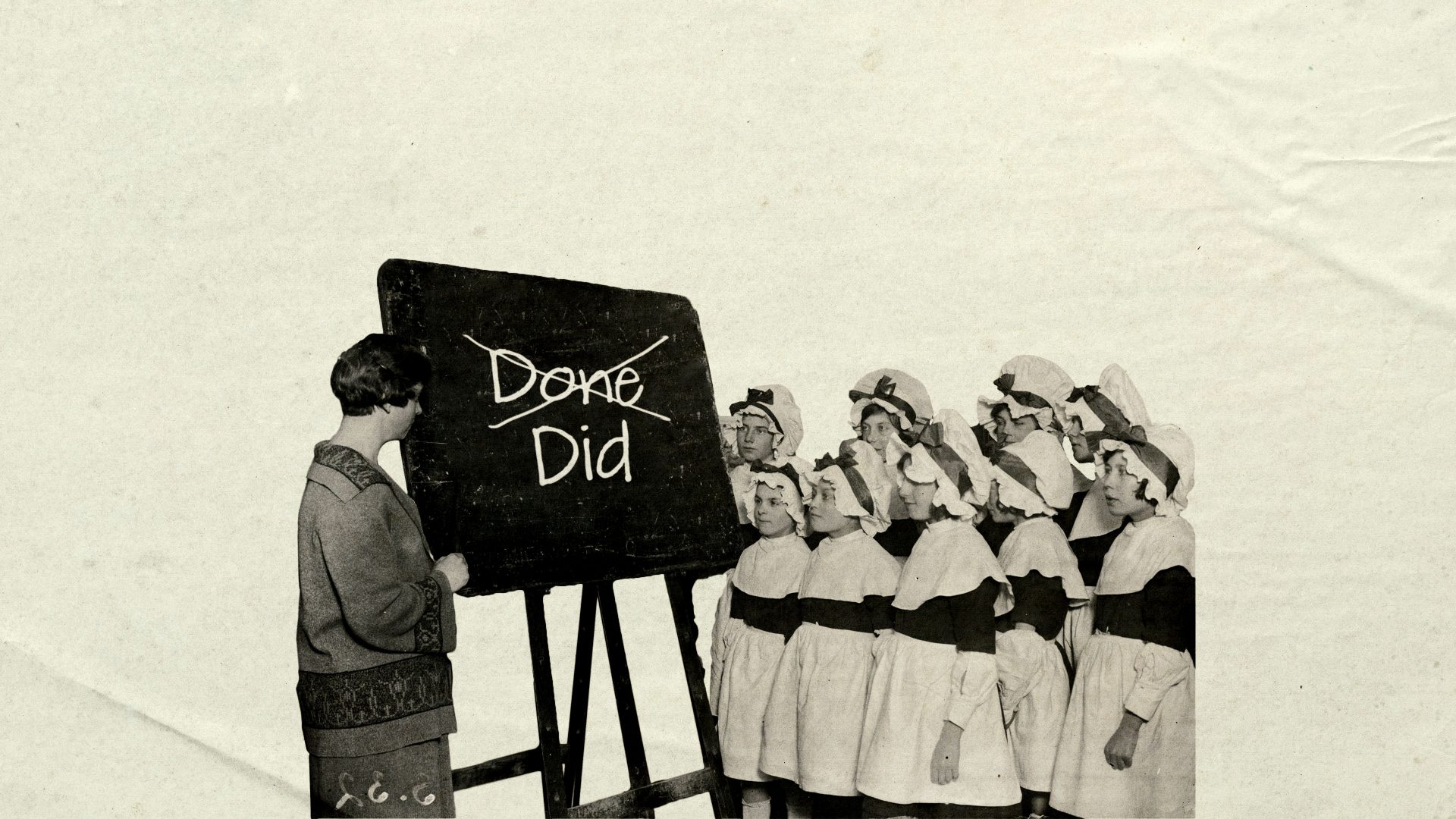

Sadly, many people also seem to think about English and other languages in terms of right and wrong. For example, the grammatical structures of the dialects spoken by a majority of English speakers require them to say “we done it”, but that will be declared by many self-appointed experts to be wrong. Why? Because you should say “we did it”, they argue.

But what type of wrong can that be? It is not inherently true that the past tense of do is did. It would make no difference to anything important if all English speakers used done rather than did. Nor does saying “we done it” constitute a deviation from equity, justice or goodness, and surely it is not immoral, unjust, or perverse.

So perhaps, then, uttering such a phrase represents a third type of wrong. Maybe we can call this the “putting your elbows on the table when eating” kind of misbehaviour, which we were told as children was wrong. This must be the sense of wrong that the OED describes as “contrary to, or at variance with, what one approves of or regards as right”. So basically it’s wrong because, according to some people, it isn’t correct.

But who are those people? What authority do they have to decide that using a particular grammatical form which is a natural part of the dialects spoken by millions of people is wrong?

We hear much these days in praise of diversity. But the regrettable truth is that, in our society, there is a widespread lack of respect for linguistic diversity. This “ideology of contempt” often seems to be most prevalent where one might expect it least: amongst the intelligentsia, the literati, journalists, the opinion-makers. There is a common view on the part of certain influential voices that some varieties of language are somehow more worthy, more valid, more correct, and in some mysterious way simply “better” than others. And, less mysteriously, it often turns out that these varieties are precisely the varieties spoken by these pundits themselves.

Linguicism

The sad fact is that currently, in this country, linguicism is much more shamelessly displayed than racism and sexism ever are. Some people who would never dream of uttering a racist, sexist or homophobic remark will still think nothing of criticising native speakers of English for having an “ugly accent”, for “speaking badly”, or for using language features which are “incorrect”.