While Michael Howard was bellowing the immortal words “prison works” to the 1993 Tory party conference, researchers, reformers and criminal justice staff in Norway were scratching their heads. Over the previous two decades, Norway had been sending more people to prison, focusing on punishment and retribution. Yet crime hadn’t reduced. In fact, Norway had a recidivism rate close to 70% during the 1980s.

Criminals were not deterred by the dire conditions in the century-old establishments. They weren’t learning the error of their ways. Upon release,

they were more likely to be reconvicted of a crime than not.

In the UK during the decades that followed, there has been no meaningful challenge to Howard’s mantra. The prison population in England and Wales has swelled from 45,000 souls in 1993 to 86,000 in 2012. It is expected to rise above 90,000 by 2026. Yet during the same period, Norway did something novel, something new. It checked the data and decided to follow the facts.

An ideological shift away from revenge and towards rehabilitation was backed by evidence collected at the independent University College of

Norwegian Correctional Service (KRUS). Whole-life sentences were abolished and the Norwegians coined their own catchphrase to counter Howard’s. If almost every prisoner will one day be released, it asked, “who would you want as your neighbour?”. In Norway, they decided a better neighbour would be someone treated with dignity and respect and given the skills and opportunities to allow for a smoother reintegration into the community.

There are numerous metrics that can be used to measure the success of a criminal justice system: recidivism rates, staff satisfaction, per capita incarceration levels, assault and self-injury statistics or community perceptions of safety. By any measure, Norway is on the right track. I saw the

evidence myself on a recent visit.

Directly in front of me, inches away from my outstretched arm, a man wields a blade. I look down the prison landing and can’t see a single officer. He smiles politely and says, “Would you like me to cut you a slice of bread?” before pushing the jam towards me.

I am in Oslo Prison in Norway. It’s lunchtime and I’m sitting at a long table stretching halfway down the wing. Officers and inmates sit and eat together, but I can’t tell who’s who. Everyone’s dressed casually in jeans and shirts and waffle-knit jumpers. The men who surround me are all tall, broad, well-fed. I look at the smorgasbord in front of me and wonder if these men would last the day on the meagre portions doled out in English prisons.

It’s not too hard to get behind the walls here. With one of the lowest recidivism rates in the world, Norwegian prison staff are used to showing around wide-eyed researchers, reformers and practitioners from all over the globe. And they’re happy to show off what they do. Because this is prison, Norway-style. And it works.

I’d been warned not to get my hopes up about Oslo Prison before I arrived. While Halden and Bastoy make headlines for their opulent conditions, Oslo was built in the 1840s, around the same time as HMPs Manchester, Pentonville and Liverpool. I’ve worked inside some of those places, and

although the narrative is that they are holiday camps, I know the reality of the dire conditions.

I’d heard rumours that Oslo was so old and decrepit, the full renovation work of the 1970s hadn’t stopped the rot. One wing was already earmarked for permanent closure just a few months after my visit. That wing was the one where I found myself sharing lunch with the inmates, marvelling at the quietness, the cleanliness and the mutual respect between all on the landing.

The month before, back in England, I’d spent days on end speaking to an inmate, Anthony, through the crack in a locked door. I leaned in close to hear him, pressing my head towards the chipping paint, stained with decades of blood and faeces. I’d been trying to assess if I could offer him any support after he’d spent the night alternately smashing his head off the wall, making cuts to his arms and being restrained by officers in an effort to keep him safe from himself. He was deemed to have no psychiatric illness and therefore, could be managed on the general wing. The officers looked exhausted, dead behind the eyes. The nurses, who visited him almost daily, were frazzled, blocking out the trauma they faced just to get through their shift.

Anthony’s behaviour was said to be, in prison parlance, ‘manipulative’. He’d looked around a real decrepit wing and realised that to get any small comfort inside a Victorian prison in England, he would need to hurt himself more, smash his head harder, cut himself, destroy his cell, before he’d get any attention from the overworked and unsupported staff. By the time I started working with him, he’d already had four custodial sentences, all of 12 months or less, for theft and drug offences.

The contrast is stark. In Norway, the rarity of such situations would have

made Anthony’s behaviour extremely alarming, warranting intensive interventions and hospitalisation. In England, it’s just another day in paradise.

As I marvel at the calmness of Oslo prison, I imagine Anthony’s screaming, the sounds of slamming gates and emergency alarms.

“Why is it so quiet here?” I ask a Norwegian officer. “Because we talk to the men,” comes the bemused reply. “We show respect and trust. It is not enough to take him out of prison [upon release], we must take the prisoner out of him.”

The differences don’t end there. Anthony was a repeat offender. In Norway, staff express disbelief when I tell them it’s normal for me to get to know the men I work with well, because their petty and persistent crimes keep them returning to custody every few months. In Norway, recidivism is perceived as a failure of the system. In England, it’s par for the course.

There is a second factor at work, too. In Norway, Anthony may not have ever ended up in prison in the first place. Norway will often divert offenders away from custodial sentences towards punishments in the community. And we don’t need to rely on anecdotes to show that short custodial sentences do more harm than good. The Ministry of Justice’s (MOJ) own data demonstrates that short prison sentences are less effective at reducing crime than community sentences. Of those sent to prison for less than 12 months, 64% will go on to reoffend within the year. Indeed, Norway’s data reveals that electronic monitoring reduces reoffending after two years by about 15%, in a country where the prison system is already often described as the most successful in the world.

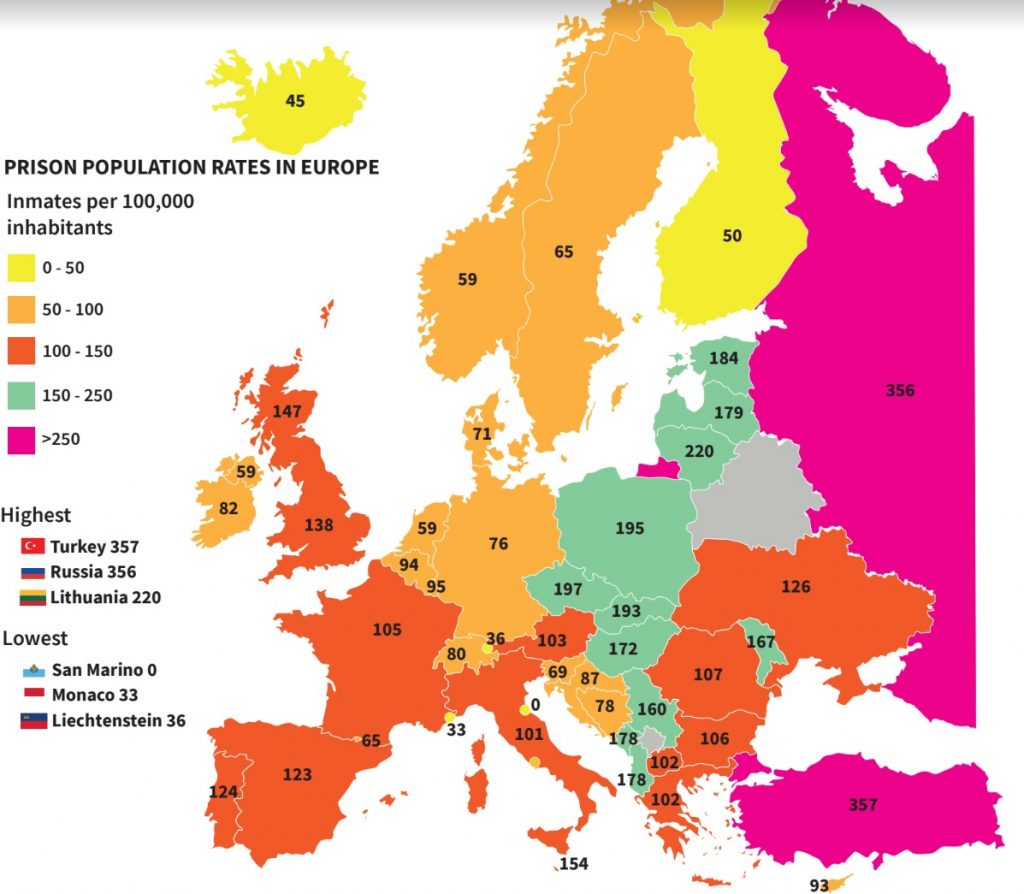

Our own government acknowledges that community sentences are a particularly effective tool for managing repeat offenders and those with mental health issues. Yet the use of such sentences has halved in the past decade. This goes some way towards explaining why Norway has a per capita prison population of 49 in 100,000, compared with 131 in 100,000 in England and Wales. With a prison population less than half that of our own, resources can then be used to focus on a robust programme of rehabilitation.

Inside prison, I could work with Anthony to calm him enough to cope for a few months, but there was no real work on why he kept coming back in, again and again. There wasn’t time for that. There wasn’t space for that. The decimation of staffing levels, the overcrowding that has plagued prisons since their inception, combined with the introduction of the synthetic psychoactive substance, spice, and its hellish consequences, meant every

effort at rehabilitation was sidelined for more imminent firefighting work.

The statistics don’t do justice to the abject failure of our own prison system, where for every two people released, one will be reconvicted within the year. In Norway, the recidivism rate sits at 25% even five years after release. England and Wales see a rate closer to 75% in the same time period.

Later, Professor Francis Pakes, a Dutch criminologist who recently spent two weeks in prison in Iceland as a ‘quasi prisoner’ in order to study their culture from within, tells me that we shouldn’t just focus on recidivism as a measure of success. “If we aim for decency throughout our criminal justice system, have decency as our goal, the reduction in reoffending will follow.”

It is this change in ideology in Norway, where prison officers must undertake three years of mandatory training in subjects as diverse as ethics, philosophy, social work and law, that has, as a by-product, reduced reoffending.

For those who believe in a more humane method of punishment, the Nordic model is a no-brainer. But it should also be considered a viable option by those whose concerns include public spending and law and order. If this method of incarceration is proven to be more effective at reducing repeat offending, it must be part of the discussion about crime and punishment, free from soundbites. To be truly tough on crime means making tough decisions that don’t feed into populist rhetoric and instead, focus directly and objectively on the data that would make our communities safer.

I travel on to Halden Prison, dubbed “the most humane prison in the world”

and the holy grail for reform advocates. While Halden is expensive in the short term – to hold one inmate for a year costs around £98,000 – the long-term cost is reduced if persistent offenders manage to step off the merry-go-round and go straight.

It costs around £44,000 to warehouse Anthony for one year in England, but he will return again and again, each year leaving a trail of new victims in his

wake as he tries to feed his drug addiction by any means necessary. On average, a Norwegian inmate commits 10 fewer crimes than if he’d not served a custodial sentence. Each one of those future offences that has been averted is a cost-saving. But beyond that, it’s one less crime, one less victim, one less frightened community.

The bill for reoffending in England and Wales is £18.1bn every single year. This is equivalent to the cost of the entire building of Crossrail over the past decade. The ten-year investment in the rails was deemed a worthy cause that would boost the economy and improve society. Yet in the criminal justice system, we throw good money after bad with a shortsightedness that is difficult to comprehend.

I am escorted past the cookery school, where every Friday a fine dining lunch is prepared by inmates and served to invited officers. The experience is complete with silver service, freshly pressed tablecloths and soft drinks served in wine glasses.

As I turn the corner, I see the chef and head waiter leaving the dining room, where they’ve just received feedback from the governor and his colleagues. The door closes behind them, they think they are unseen, and they suddenly begin embracing, high-fiving, congratulating one another and giddily celebrating the success of the lunch service.

They see me and quickly stop, but the moment highlights so exquisitely how the environment is a foundation from which they can build self-esteem and skills and an identity beyond that of a criminal. It demonstrates how building real skills that lead to real employment opportunities in the community can put a stop to the cycle of reoffending.

The chef, Jon, is gaining catering qualifications. The certificate he’ll receive is to the same standard as he’d get out in the community. It won’t be mentioned anywhere that he gained it in custody.

I ask if he’ll need to declare his offending history when applying for work. He says he’ll probably tell prospective employers at the interview, but not on the application form. He feels he’ll be able to get a job relatively easily upon release, the stigma of time in custody apparently not the issue it is in the UK. There is a feeling of hope, that past actions will not affect future choices. He believes going straight is possible, if he puts his mind to it.

Norway’s approach may be based on the slogan “who would you want as your neighbour?”, but it is also economically sound. Although the initial outlay is costly, there are positive economic benefits to this approach, including the increased likelihood of released prisoners entering the workforce. Research shows that the men who access training and education inside Norway’s prisons typically didn’t have a history of secure and sustained employment before incarceration. Prison doesn’t support them to get back into work: for many, it brings them into the workforce for the first

time. The reduction in social security payments and the increase in tax

collected all feeds back into the economy. Of those who were unemployed before entering prison, there is a 40% increase in employment. Norway doesn’t just rehabilitate, it creates good neighbours out of people who were

never previously active, taxpaying citizens.

Meanwhile, work opportunities in our own prisons are often mindless and repetitive. Of those who managed to work at some point during their time in custody, only 43% of men reported that the work they carried out would help them on release. Less than 24% reported receiving help to secure employment upon release. While Norway creates tax-paying citizens in its prisons, in England and Wales, only 10% of men and 4% of women have paid employment six weeks after leaving custody.

Prisoners in Norway aren’t innately better behaved, or less troubled, than men like Anthony. On the substance misuse wing, Jon shows me his cell. He relaxes now he’s back in his own space, and rolls up his shirt sleeves. My social work-trained eyes dart to his arms, taking in with one glance the scars and skin grafts that indicate decades of intravenous drug use.

“I was a dangerous man,” he tells me, as he shows me around his single-occupancy cell that is bathed in late afternoon light pouring through unbarred windows.

“I have had lots of problems in my life,” he says. He tells me about the raging heroin addiction he had before his arrest, the charges for assault and robbery. It’s a reminder that for all the praise Norway receives, there are still

people who struggle to follow society’s rules, who fall through the cracks. The difference is that when they do, a whole community of support staff surround them to pull them back up. The opportunity to become a productive, active member of society is available to Jon, if he chooses to take it. Jon is treated with decency, and because of this, he is thriving.

He’s keen to play down the facilities at Halden, which include a bathroom in his cell, complete with a door that he can lock behind himself for privacy while using the facilities. “It’s different here. The staff are calm. I feel safe. If I need to talk, there’s always someone available.”

The wings are flooded with staff. Psychologists, psychiatrists, teachers. But also officers whose training includes ethics and social work and psychology. “The space is nice, yes. But they report that this is a hotel. Don’t forget that I’m locked in. Once I’m released, I don’t ever want to return.”

I explain that in England, we lock two people in a cell, often for 23 hours a day and expect them to eat, sleep and defecate in the same space. “How do they cope?” he asks, looking upset at the thought of English conditions.

A crowd of inmates starts to gather and they all chime in. “I’d just fight if I was forced to share.” “Don’t they get bullied?” “I wouldn’t feel safe.”

These men tell me that they’d all likely behave like Anthony if they were thrown on to overcrowded wings with no meaningful opportunities for

rehabilitation provided. I wonder if Anthony swapped places, would he now be planning a brighter, crime-free future, too?

Statistically, the more overcrowded an establishment in England and Wales, the higher likelihood an inmate will die by suicide. In the year before the pandemic put all of our prisons into lockdown regimes, 9,995 assaults on staff were recorded and self-injury reached a record high of 63,328 incidents.

It is worth reiterating that Halden is a maximum-security prison, filled with prisoners who have committed serious crimes. Yet a model based on the principle of rehabilitation, with dignity and respect at its core, doesn’t suffer these shocking statistics.

If our own system of incarceration was working, whether for deterrent,

incapacitation or rehabilitation, it would surely have borne fruit by now. Her Majesty’s Victorian prisons have stood sentinel over our major cities for nearly two centuries. Yet the more people we lock up, the more crime is committed. The National Audit Office can draw no link between increased

incarceration and a reduction in crime.

Pakes, when asked if prison works in England and Wales, on any metric, replied that “it works symbolically.” We have an obsession with prisons in the UK, yet we underfund and under-resource them at every stage. And this

symbolism goes no way towards reducing crime.

But what about the victims? To truly respect victims, we should strive for a

criminal justice system that keeps us safe and prevents any more people from becoming victims of crime in the future. And the data shows that longer, harder and more punitive sentences don’t achieve that.

The fight for an evidence-based approach is the kind of toughness we should expect from our politicians: the toughness to pursue policies that make us all safer, save costs in the long term and reduce crime. Meanwhile, Dominic Raab steams ahead with handing out private contracts for 20,000 additional prison beds by 2026. The conversation around any alternative has been silenced.

The opposition, too, knows our current system of “lock ’em up” doesn’t work and any politician worth their salt can see that a Norwegian system reduces the number of potential future victims. But there is a fear that deviating at all from the “prison works” narrative is political suicide.

Yet the well-worn trope, of being the party toughest on crime, doesn’t serve

anyone when ‘toughness’ equates to banging them up for an indefinite period, only to release them in a worse position than when they started. This retribution may make us feel better, but it does not rid our communities of crime: it exacerbates the problem. No amount of rhetoric should distract from this. It’s hard to stand up against those screaming for revenge, but this is what it truly means to be tough on crime.

I return to the prison in England just in time to see nurses tearing down the landings carrying medical equipment. Anthony has overdosed. They spend an hour working on him, bringing him back to life. He is released a week later, with no fixed abode. Six months after that, he returns to custody.

And I realise that Michael Howard was right in 1993 when he said “prison

works.” He just wasn’t talking about the right model.

Criminal: How Our Prisons Are Failing Us All by Angela Kirwin is published by Trapeze, £18.99