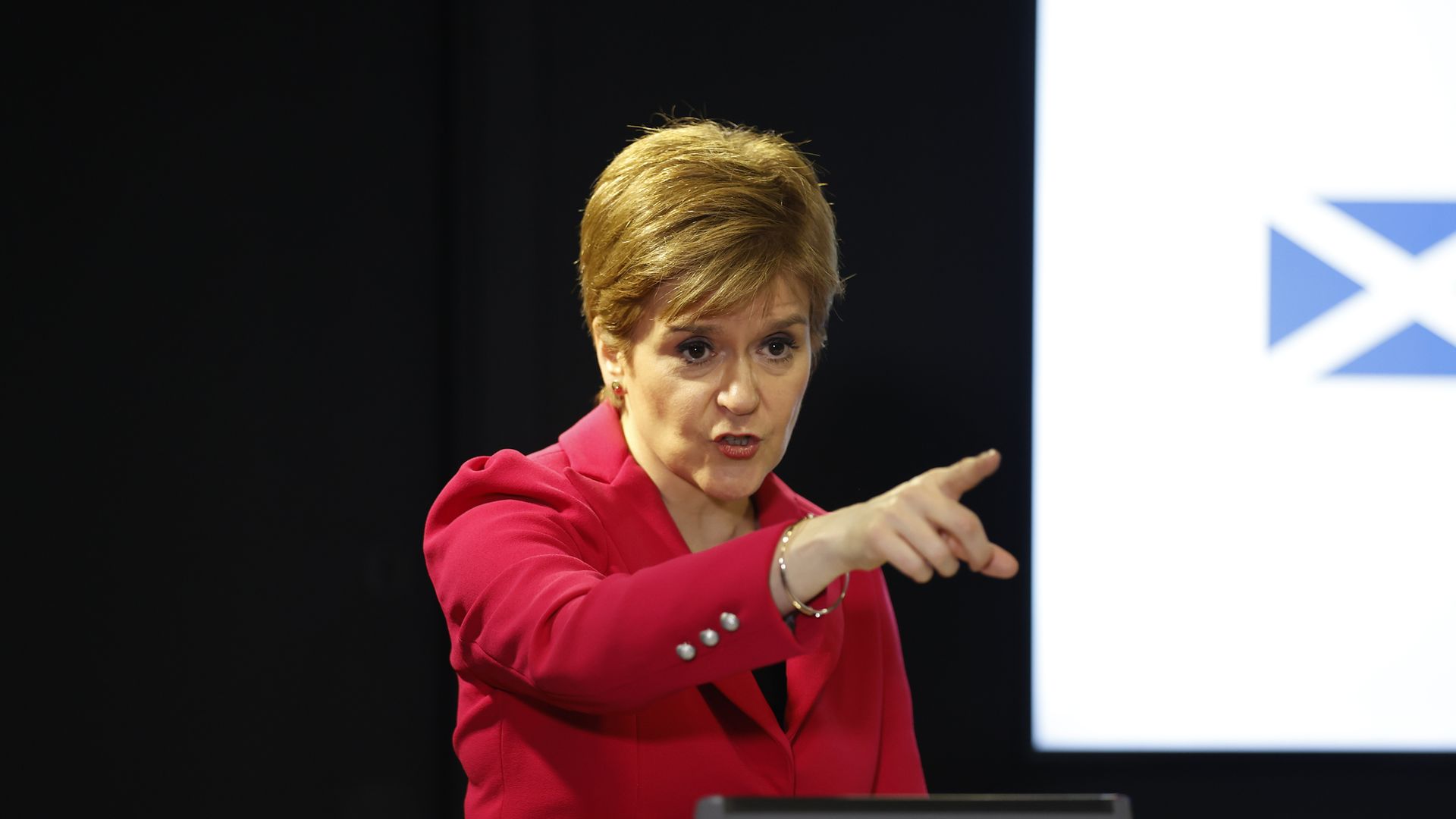

On September 19, 2014, at around 2am, I watched Nicola Sturgeon arrive at the count for the Scottish independence referendum in Glasgow. She knew she had lost. But she was greeted rapturously, both by the Clydeside SNP hierarchy and by scores of young, left-wing activists from the radical independence campaign, who mobbed her like a rock star.

It was not so obvious then, but that was probably the high point of her political career. Alex Salmond was about to resign. She would take over as first minister of Scotland.

But in the nine years that followed, despite resounding victories at Holyrood and her steely management of the Covid 19 pandemic, Sturgeon has made not one inch of progress towards her stated goal, which is independence for the Scottish people.

I came away from Glasgow that week convinced that I would see independence in my lifetime. When Rangers-supporting 16-year-olds tell you they want an end to the Union, “despite supporting the wrong football team” it’s a sound bet that, within 20 years if not ten, that is what they’re going to get.

Sturgeon’s party, it seemed, had created an unstoppable cultural ethos around separation with an irreparably Tory England. On the overnight sleeper train, the Scottish computer programmers and lawyers who inhabit the bar convinced me that it was only a matter of time.

So why, after Sturgeon’s sudden resignation, does the goal seem distant? Why, having staged her challenge in the law courts, and threatened to call a “de facto referendum” at the next UK General Election, does Sturgeon leave the independence movement in disarray?

The first thing to say is: it’s nothing to do with her personality. I found Nicola Sturgeon a breath of fresh air in British politics. Yes, she did realpolitik – as her management of various Holyrood scandals showed. But she did it- as far as I can see on the evidence – straight. She sacked colleagues who broke the rules. She did not seek personal gain. She managed an inevitably cliquish party well, and allowed genuine talent to thrive.

Sturgeon failed because she never confronted the economic reality behind the demand for outright Scottish sovereignty. She was dealt a perfect hand, two years after the independence referendum, by the shock victory of the Brexiteers.

Reality had changed; the case for Scotland leaving Britain in order to remain in Europe (or rejoin it) looked strong.

To make it properly, however, Sturgeon would have to do what Salmond failed to do in 2014. Tell a coherent story of how prosperity could be achieved outside the United Kingdom.

“Scotland’s Future”, the independence White Paper of 2014, had been a weak and semi-fictional prospectus. To seal the deal with sceptical conservative and middle-class Scots, Sturgeon would have to tell a better story. That was the rationale behind the Sustainable Growth Commission, whose 2018 report, Scotland The New Case For Optimism, became iconic in Sturgeon’s SNP.

The case for optimism, it turned out, was based on austerity. En route to an independent Scotland, the country would be forced to run a massive budget deficit and cede monetary sovereignty to the Bank of England, by retaining sterling as its currency. Its people would be forced into huge economic sacrifices for the political goal of freedom from Westminster. And the whole thing was premised on long-term dependence on oil and gas.

Unappealing though it was to the left wing activists who had hugged Sturgeon in 2014, you could at least say the Growth Commission report was realistic. Ten years of economic pain would lay the basis for a Scottish currency. The immediate gains would be cultural and political.

But it was also a huge turnoff for the outright nationalists in her party, who wanted monetary and fiscal sovereignty from day one. Add that to the cultural battles they began to fight – against transgender rights and “wokeness” – and you begin to see why Sturgeon’s project fell apart.

At a deeper level, Nicola Sturgeon failed because, after 2014 she refused to be a major player in British politics. That’s the right of all separatists: to shape their priorities around the devolved assembly and its powers, the politics of language and national identity, and to ignore Westminster. But if you adopt that strategy, at some point – as Irish nationalism did in 1919 – you have to deliver actual separation.

Sturgeon understood this: that’s why she fought for the right to hold a referendum in defiance of Westminster, and toyed with the idea of a “de facto” referendum at the next general election. But she could not deliver it.

Meanwhile, despite sterling work by individual SNP MPs at Westminster, the party has always seemed less than the sum of its parts at a UK level. It looks disengaged from the polity it is part of, and focused on a future that never seems to come.

As a socialist, I support the right of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to secede from the UK, should a majority of their people vote for it. But the Liz Truss episode shows the fire you are playing with if you rely on hit-and-hope economics. States that cannot borrow or service their debts, and who are compelled to obey a foreign central bank, are sovereign in name only: their policies are always dictated by the bond market.

Until the Scottish independence movement comes up with a single, validated and evidence-based story about how it’s going to avoid bankruptcy or austerity – let alone how it guarantees national security in an age of acute threat – it won’t win another referendum.

That doesn’t mean the breakup of the UK is off the agenda. Just that it will take time and different circumstances. And while that clock is ticking, it’s sensible to play an active part in the politics of the whole UK.

As the SNP looks for a replacement for this most formidable of leaders, it is these issues – not Sturgeon’s alleged “wokeness” – that should decide the outcome.