It has held it together, shown a surprising cohesion and a determination to face down Kremlin aggression. Yet Europe faces at least as much tumult in 2023 amid fears that popular support for the tough line could weaken and that American solidarity with the continent will fray.

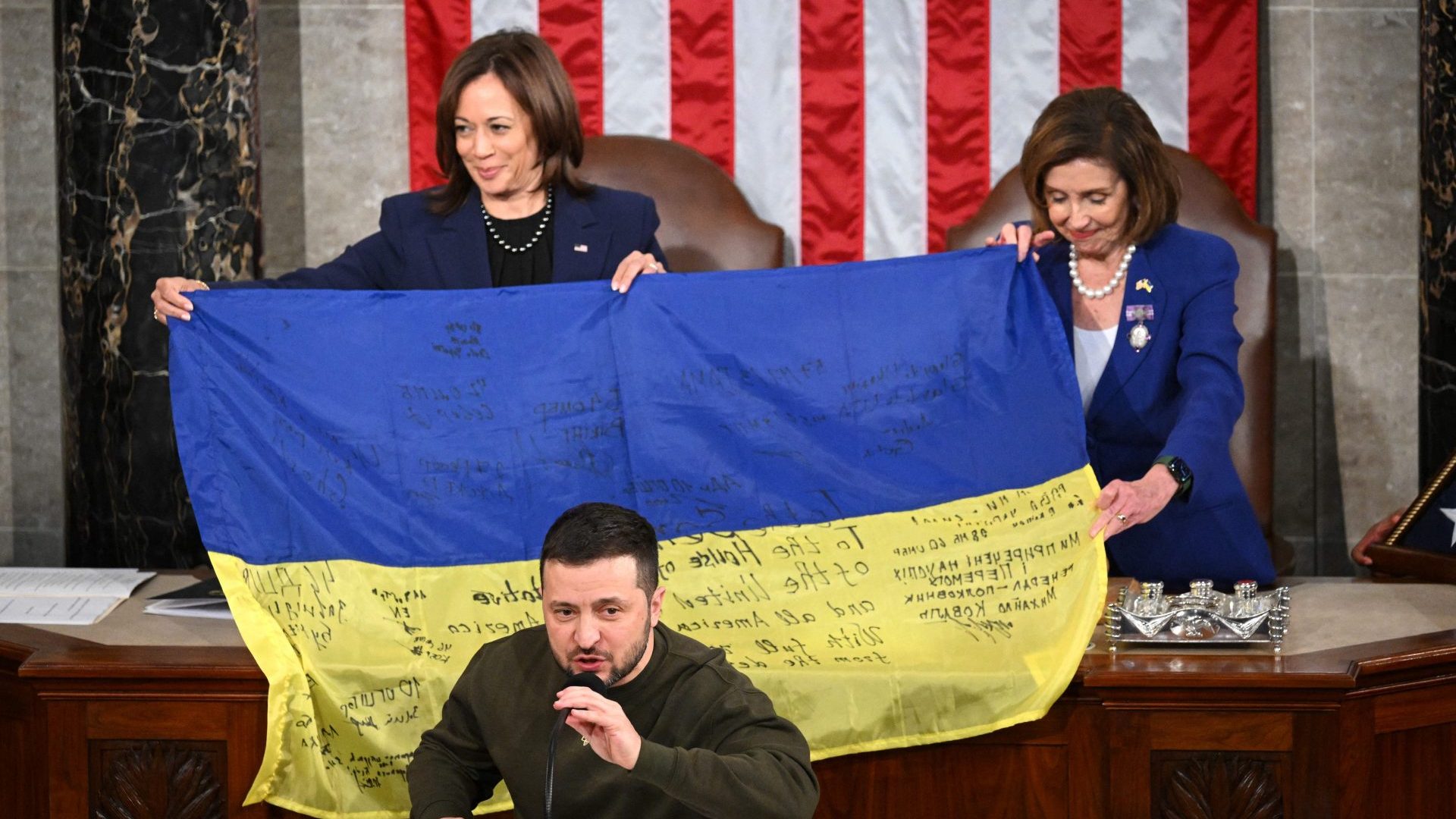

In the last month of 2022, as fears mounted of an imminent major Russian offensive, Volodymyr Zelensky stepped up his diplomatic efforts to persuade his allies not to give up on him. His dramatic 10-hour dash to Washington earned a succession of standing ovations from Congress and bought him $2 billion worth of Patriot defence system, but not what he wanted most: American battle tanks, fighter jets and long-range precision missiles.

It has only given Zelensky and Ukraine a few months’ advantage. And, with the House of Representatives set to have a Republican majority (some of whose members stayed away from the president’s address), this pre-Christmas trip might just mark the peak of US support.

Equally important in December was Vladimir Putin’s trip to Minsk, during which it was assumed he instructed his poodle-neighbour Alexander Lukashenko to commit Belarussian forces directly into the war effort. So far Lukashenko has handed over air bases and air space to the Russians, but not his own troops.

In the third piece of summitry, and the one almost completely ignored by mainstream UK media, as it does with what is happening in the alien city of Brussels,) European Union leaders agreed a new €18 billion financing package for Ukraine, more sanctions on Russia and an agreement to cap natural gas prices.

Three trends are at work, and they are all potentially damaging for Ukraine: a waning enthusiasm across the West to keep funding Ukraine (the “blank cheque” syndrome); a lack of cohesion within the EU; and increasing tensions between the US and Europe.

The catalyst for the latter is a piece of legislation with the unfortunate acronym IRA – the Inflation Reduction Act. Passed in August, it provides $430 billion worth of subsidies and tax breaks for US companies on green transition. Its signature policy element is a tax credit of up to $7,500 for purchasing new electric cars, but only vehicles assembled in North America are eligible.

In theory, it is a necessary part of a wider Western initiative to “onshore” or “near-shore” critical industries, weaning companies away from over-reliance on China. The law amounts to a massive use of government power to ensure that solar projects, electric vehicles and associated supply chains are not imported but built in the United States. The problem is that it does not discriminate between potential adversaries and long-standing allies.

During a recent state visit to Washington, Emmanuel Macron lobbied in public and behind the scenes for the Biden administration to think again, or at least to mitigate some of the worst effects of the IRA. The French president was garlanded at a banquet and reassured by his host that transatlantic relations remain as strong as they have ever been.

But his diplomacy fell on deaf ears. The US is more or less daring the EU to take the issue to the World Trade Organisation, knowing that litigation takes years and might never be resolved, since the WTO’s legal body lacks a quorum of judges.

It seems that there is little Europe can do except to copy the Americans. European business is putting pressure on Brussels to relax its own state-aid rules to allow individual companies to subsidise their own nascent green industries. The EU Commission would have to come up with a bloc-wide plan, to ensure that member states do not undercut each other.

The other gripe is US inflexibility on gas prices. American companies continue to charge Europe four times more for natural gas than it does its domestic customers. Legitimate profit or profiteering, US producers know that the more they divest from Russia, they have other countries over a barrel. The same goes for the likely surge in orders for American-made military kit as European armies run short after sending weapons to Ukraine.

Whenever he is criticised, Biden acts nonplussed, showering European leaders with yet more praise. He is doing “America First” without the belligerence of Donald Trump; it is a much more potent tool because his allies do not know how to respond.

US legislators and commentators are less prone to emollience, counter attacking on two fronts. They remind their allies that the US has by far been the largest provider of military aid to Ukraine – more than the whole of Europe put together. As for equipment shortages, they note that successive presidents, Democrat and Republican, have been urging European states to step up to the target agreed back at the 2014 NATO summit of spending 2% of overall GDP on defence. Very few even came close.

Suddenly, Ukraine has changed everything. On one level perhaps. Since Putin’s invasion, Western allies have shown remarkable cohesion. That is now fraying not just because of immediate differences, but also because of long-term priorities.

With an increasing amount of attention focused on the bigger challenge of China, and with the first skirmishes in the US presidential election set to begin, transatlantic relations will be put to the test. It feels as if Europe hasn’t moved on from 1952 when the first NATO secretary general Lord Islay famously summed up its strategy: “To keep the Russians out, the Americans in and the Germans down.”

Even before last February, European policymakers were warning of the need for “strategic autonomy” to be less reliant on the US. The quip in Germany (funny and true) was that the country had for too long been dependent on America for defence, Russia on energy and China for trade.

The government in Berlin has done an incredible job in weaning the country off Russian energy. The share of Russian gas has been reduced from more than 50% to next to nothing in barely six months, thanks to securing LNG terminals from Norway, Qatar – and the US. Even though blackouts are unlikely in the next few months, some are predicting that the energy crunch across Europe could lead to 100,000 excess deaths among the elderly and vulnerable. The even bigger concern is not the current winter (getting through to March), but the one that starts at the end of 2023.

The Commission and member states have done a commendable job in dealing with the immediate energy and economic dangers. On the political front, the biggest questions remain unanswered. How will Europe achieve greater strategic autonomy when it struggles to know what it wants? Some countries like Italy and Spain want a preparation for a “return to normal” once the war is over; not a life as it was before the invasion, but a willingness to engage Russia as a player. Hungary under Viktor Orban remains the outrider, keen to accommodate Putin while just doing enough to stay within EU confines.

Some, like the Balts and the Nordics (and of course the Brits but they no longer have any say), are delighted that the US is back front and centre of European politics. Presidential elections in the Czech Republic in January could lead to the return to the frontline of former prime minister Andrej Babiš – a populist, close to Orban and sympathetic to Russia. A less isolated Hungary will be an even greater irritant.

The biggest obstacle to European cohesion lies less in its extremes, however, and more at its heart. French presidents and German chancellors have had many a marital tiff, but the rift between Macron and Olaf Scholz is one of the deepest of all.

Each has tried to outshine the other on the world stage – Macron in Washington, Scholz in Beijing. Each has made important announcements without discussing it with the other in advance, something their predecessors would have sought to avoid. Scholz’s people resent Macron’s preening (his ostentatious descent onto the pitch at the World Cup final to console the French players was a huge source of mirth in the German media). The French were furious when the chancellor refused an offer of a joint trip and went on his own, with business leaders in tow, to meet Xi Jinping.

Both sides are in the midst of rows over energy (France likes to remind Germany of the merits of nuclear) and over defence procurement (the Germans have gone cap in hand to the Americans for fighter jets, circumventing the French defence industry).

A ministerial council (a meeting of both cabinets) was supposed to take place in Fontainebleau in October; it is now scheduled for later in January. Celebrations of the diamond jubilee of the Elysée Treaty will take place, whatever the undercurrents.

Meanwhile, the war grinds on and Ukrainians cower under barrages of Russian missiles and Iranian drones. Zelensky needs Europe to stay united; he needs the US and EU to continue to work together, and he needs European voters not to lose faith. That is his anguished wish list for 2023.