For most people in Longarone, nestled in the Dolomite mountains, in the shadow of the Vajont dam, there was no warning of the fate that was about to befall them. October 9, 1963, was a cool, clear night. Many had gathered in friends’ houses or local bars to watch the European Cup tie between Real Madrid and Glasgow Rangers.

Suddenly at 10.39pm, there was a deafening noise like a jet engine that “roared down the streets in a screaming fury”. Then the lights went out. The televisions flickered off.

High above the town, around 270m cubic metres of rock and earth, equivalent to four solid Wembley stadia, had sheared off Monte Toc on the south side of the reservoir created by the dam. Accelerating at 30 metres per second – the speed of a Formula 1 car – it crashed into the water in just 45 seconds.

In turn, this created a mega-tsunami that engulfed the shore opposite, destroying houses in the lower parts of the villages of Erto and Casso. Then the massive wave dispersed, the majority heading downstream, overtopping the 262-metre-high dam by nearly 250 metres. Thirty million cubic metres of water, enough to fill 12,000 Olympic swimming pools, cascaded into the valley below from a height of half a kilometre. The tremors caused when it hit the ground were so strong they were recorded in Vienna and Brussels.

The displaced air ahead of the wave exerted the force of two Hiroshima bombs, destroying almost everything in its path before the deluge arrived to wash away the debris. By 10.43pm the villages of Pirago, Rivalta, Villanova and Faè and the town of Longarone had been erased from the map.

So great was the amount of water that flooded the valley, so great the destruction and, in the darkness and eerie mist, the confusion, some even thought it might have been the start of a third world war, a genuine fear since the Cuban missile crisis a year earlier.

Local journalist Tina Merlin was one of the first on the scene. As she was held at a checkpoint in Ponte nelle Alpi some seven miles south of Longarone, she watched as the Piave River rose alarmingly. It was clogged with debris and, increasingly, corpses. The horror of what had happened hit her. She rang her office, telling them “there are hundreds of dead”. It was a tragic underestimate.

The largest peacetime disaster in Italian history officially claimed 1,917 lives, although the true total is believed to be as high as 2,500. At least 457 of the victims were children. Around 350 families were wiped out altogether. The majority of those who died were in Longarone, where the fatality rate was 94%.

Of the 1,464 bodies recovered, only 703 were identified. For many there was simply no one alive to do so. Others were never found, either buried too deep in the mud, which quickly solidified, or swept out into the Adriatic Sea.

Most newspapers, frantically rewriting their early editions, reported that the dam had collapsed catastrophically. However, when dawn broke it became clear that, apart from minor damage to the top, it was still very much intact.

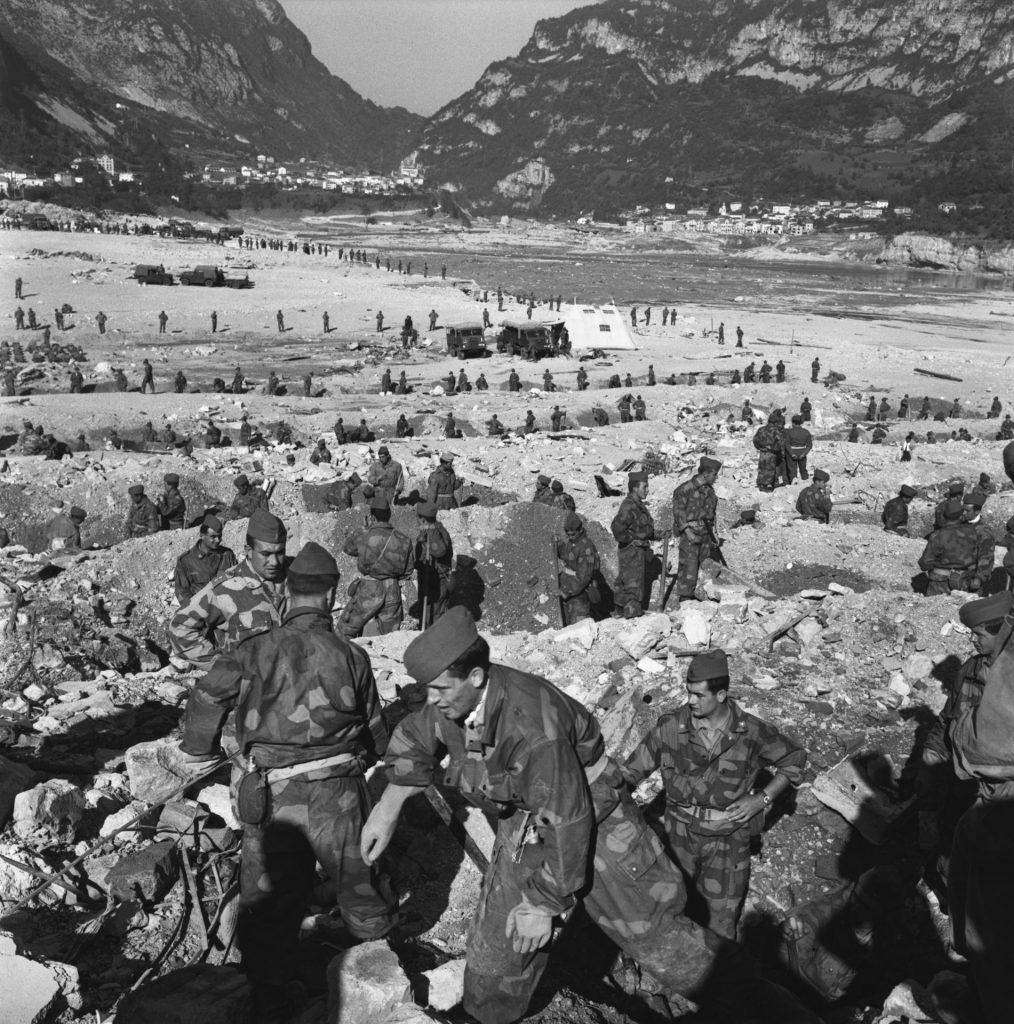

With roads and railway lines destroyed, rescue teams struggled to reach the disaster site. When they did, they found that a once lush, verdant valley dotted with houses had been transformed into a vast, desolate mudscape.

Conceived in the 1920s during Mussolini’s reign, work on the dam began in 1957. When it was completed three years later, it was the second highest in the world, around 40 metres shorter than the Eiffel Tower. The geology of the Vajont River valley, about 70 miles north of Venice in the Dolomite region of the Alps, was ideal for creating huge reservoirs: deep, narrow gorges cut by prehistoric glaciers.

However, like much of the area, the 4,800ft-high Monte Toc was composed mostly of limestone rock. Although it looked solid, it was in effect a huge pile of rubble held together by little more than friction, and it was prone to regular landslides. The locals dubbed it “the mountain that walks”.

Throughout construction, they reported tremors and rockfalls. Their fears of potential tragedy were ignored by the Società Adriatica di Elettricità (SADE), the company responsible for construction.

This intransigence was in part born of ignorance; few believed the entire side of a mountain could shear off in one go. It was also the consequence of economic pressure. The dam was a crucial part of a complex system of hydro-electric plants all built by SADE to fuel the postwar industrial boom in Italy’s northern powerhouse. Nobody was willing to call time on such a costly and important project.

“There was certainly concern among the inhabitants that a disaster could happen,” says Roberto De Nart, editor-in-chief of Bellunopress, an online newspaper covering the area. “But ordinary people were powerless in the face of the economic power of SADE. As always happens, money was considered more valuable than human lives.”

In early 1960, SADE began filling the newly created reservoir. What had once been steep valley walls rising above the Vajont River were submerged beneath hundreds of feet of water, becoming further destabilised

In October 1960, with the depth of the reservoir at around 170 metres, a huge fissure just over a mile long opened on the south side. The face of the mountain below the crack began sliding at a rate of approximately 3.5cm a day.

The following month, after a week of heavy rain, around 700,000 cubic metres of rock and earth slid into the lake over the course of about 10 minutes, causing a seven-ft-high wave. There were no casualties and no damage.

As the water level was reduced in response, so the displacement of the mountain slowed, to about 1cm a day. Thus, the dam’s engineers believed that by raising and lowering the water they could create a controlled landslide. They calculated that as long as any collapse did not happen in less than 10 minutes, the resulting wave would not over-top the dam.

“It was reckless in the extreme,” says Prof David Petley, a geologist who has studied the causes of the tragedy. “You could only possibly do that if you properly understood what the landslide was doing, its mechanics and its processes. They just did not have the level of knowledge to be able to make that judgement.”

Over the course of the next three years, the engineers pursued their flawed plan, and it appeared to be working. However, crucially in their geological investigations, they had failed to unearth a seam of clay around five to 10cm thick just below the rock. In effect, this acted as a lubricant, reducing the all-important friction holding the mountain together. Furthermore, it was tilted down towards the reservoir.

“That thin clay layer was absolutely critical,” says Petley. “Had they found that, they would probably have had enough evidence to question their own decision-making, but without it I think they were able to convince themselves it was OK.”

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the Italian government and SADE were quick to claim it was an unavoidable natural disaster. “The pressure meant Mario Fabbri, the investigating judge, was forced to look abroad for people willing to investigate the causes of the landslide,” says De Nart.

Eventually, 11 employees were charged with negligence and manslaughter. One committed suicide and two others died before the trial. Of the remaining eight, three were convicted in 1971. No one spent more than two years in prison.

The trauma was compounded by the treatment of the relatives of the dead. In many cases, life insurance policies and pensions were not paid because the documentation had been lost, washed away with the victims. Any compensation paid was derisory: 1.5m lira, the equivalent of around £11,000 today, for deceased children, less for other relatives. Many, emotionally shattered, accepted the money.

Others refused and in 2000, 37 years after the disaster, a civil suit for damages was settled. The government and two companies, one private and one state-owned, that had superseded SADE, agreed to pay 900bn lira (£500m today). By then, Longarone had been rebuilt, along with a new town of Vajont founded to resettle survivors from elsewhere.

The tragedy is little known outside Italy. Nonetheless, it has had a global impact. Attitudes towards the safety of large infrastructure projects were completely overhauled as a consequence. Comprehensive risk assessments became the norm. No dam can now be built without the plans demonstrating that it will not cause a similar tragedy.

In 2008, the UN described Vajont as an exemplary case of “avoidable disaster”.

There have been calls to demolish the dam, but these were half-hearted at best.

“It would be like erasing all traces of the tragedy from the collective consciousness,” says De Nart. Instead, it remains, a testament to the engineering skills of those who built it, albeit rendered useless by the huge mass of rock that fell into what was the reservoir. It is now a tourist attraction, a bleak memorial to mankind’s ingenuity and also stupidity.