It was the birth of sportswashing. When Italy’s captain, Gianpiero Combi, lifted the World Cup after the 1934 final, it wasn’t just a victory for the host nation, it was also a victory for Benito Mussolini and fascism.

In the 1930s, sport was becoming increasingly globalised, and tournaments organised by world governing bodies were growing in stature. As they did, they were ripe for exploitation by countries that wanted to both project a positive image to the world and instil their values into the domestic population.

The 1936 “Nazi” Olympics in Berlin are perhaps the most infamous example, but Italy had set the template with the World Cup two years earlier.

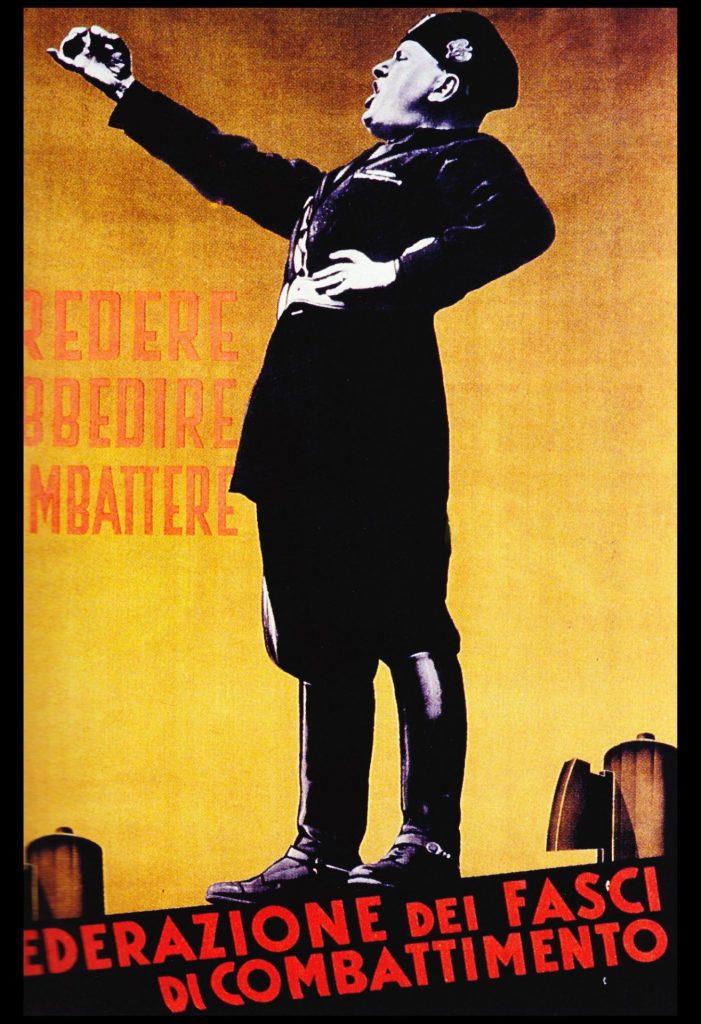

Il Duce came to power in 1922, and as part of the “cult of the leader” he was regularly depicted on horseback or skiing bare-chested – the “leading sportsman in Italy”. Four years later, the Dopolavoro (Afterwork) programme was launched to foster a healthy population and promote community spirit. Within a decade, it oversaw some 20,000 local sporting organisations and around 130,000 competitions for millions of players and spectators.

“Sport touches absolutely every aspect of life under the fascist regime,” says Prof Simon Martin, author of Football and Fascism. “The regime projects every policy it wants through sport. That can be foreign policy, economic policy, demographic policy, imperialism, propaganda, ideas about gender. There’s nothing that sport can’t reaffirm.”

Mussolini’s regime had applied to host the first World Cup in 1930, but withdrew in favour of Uruguay. It then applied to bring the 1936 Olympics to Rome, but again withdrew on the eve of the vote in the hope that doing so would guarantee it the 1944 Games. Subsequently, it turned its attention back to the World Cup, and was awarded the 1934 tournament.

“They’re interested in international competition because it projects a great image of the regime abroad and also domestically,” says Martin. “It’s also about bringing in tourists and bringing in money, but not just money, good money that is stronger than the Italian lira.” Subsidies covering as much as 70% of travel costs enticed thousands of fans from across Europe. Once in Italy, journeys between host cities were heavily discounted.

The tournament was also an opportunity for the fascist regime to show that it could do more than just make the trains run on time. Host cities were chosen because of their aesthetic beauty and, crucially, their embrace of modern, fascist architecture, of which sports stadia were an integral part.

These were not just places to go to play or watch football; they also had an important propaganda role. The architecture, which drew on the country’s Roman past, was designed to show the prosperity, strength and work ethic of the Italian people. “When those tourists come, they see these cutting-edge stadiums,” says Martin, “but also, they see the enormous redevelopment works throughout the country.”

A new cigarette brand, Campionato del Mondo, with packets depicting a ball in the net, was launched to profit from football fever. Fascist symbolism was also infused into the marketing of the tournament in numerous ways. Some 300,000 postcards were produced and a national competition held for the tournament poster design. The winner showed a football with the world in the background and the fascist symbol of rods tied to an axe in the bottom left corner. Another showed a player giving the fascist salute. However, it is a third, more internationalist design of a player kicking a ball in front of several countries’ flags, which lacks any overt fascist symbolism, that became the enduring image.

The regime also used the tournament as an opportunity to spread its iconography abroad. Tickets were printed on high-quality paper and care was taken over their design, in the hope that they would be kept as souvenirs by travelling fans.

Around a million commemorative stamps were put into circulation. “Stamps are really important,” says Martin. “What do people do with stamps? They send postcards back home and the stamps are symbols of the regime.”

The media also played a key role in framing the tournament for the domestic audience. Newspapers not only provided reports on the games, in which the players became “soldiers of sport” and “athletes of fascism”, but also the organisational and financial success of the tournament.

The new medium of radio was important, too. Although ownership in Italy was relatively low compared with other European countries, the regime invested heavily in cutting-edge technology, led by Mussolini’s brother Arnaldo as head of the state broadcaster.

Sales of radio sets rose considerably during the tournament, not least because of the flamboyant commentary of the legendary Nicolò Carosio. “He’s the voice of fascism, he’s like a fascist David Coleman. He’s emblematic, his voice represents that era,” says Martin. For the first time, the rights for radio commentary were also sold abroad (although not to an aloof and absent Britain).

Thirty-six teams entered the tournament, although this did not include the reigning champions Uruguay, who refused to take part in retaliation for several European countries not travelling to South America four years earlier.

England, still widely considered to be the world’s best, did not take part either. Along with the other Home Nations, they chose to focus insteadon the British Home Championship, which FA committee member Charles Sutcliffe claimed was “a far better world championship than the one to be staged in Rome”.

To whittle the field down to 16, qualification games were played on a geographical basis for the first time. Twelve places were allocated to Europe, three to the Americas, and one to Asia and Africa. For the only time in World Cup history, the hosts also had to qualify, which they did with an easy 4-0 win over Greece.

There was no group stage as there had been at the first World Cup four years earlier. In another example of the regime’s organisational capabilities, all the first-round games were played on the same day and kicked off at the same time. This was also in line with Mussolini’s fascist philosophy: the “weak” teams would be knocked out “with one punch”.

Marshalled by Vittorio Pozzo, a former elite ardito soldier, the hosts cruised through the first round, beating the USA 7-1. They then faced Spain in a quarter-final that ended 1-1 and is infamous for its brutality, and controversial refereeing. The Italian Mario Pizziolo broke his leg and was never able to play for the team again while the Spanish goalkeeper-captain, Ricardo Zamora, was injured, some say illegally, as Italy equalised.

In the days before penalty shootouts, a replay was scheduled for following day. In another brutal affair, Italy won 1-0. Spain were without their injured talisman, Zamora, who said the game “should have been the final – we were the best teams”.

Austria’s Wunderteam were dispatched in the semi-final 1-0. Then on June 10, in the searing heat of Rome’s Stadio Nazionale del PNF (National Stadium of the National Fascist Party) Italy beat Czechoslovakia 2-1 after extra time. Following the triumph, the Azzurri received not only the World Cup, but also the Coppa del Duce, which Mussolini had commissioned and which was six times larger than the official trophy. They also received a signed photo of Il Duce – who broke off the celebrations for a summit with Adolf Hitler in Venice on June 14 – and a gold medal.

Numerous rumours and accusations of corruption abounded at the time, including the suggestion that Ivan Eklind, the Swedish referee who took control of Italy’s semi-final, dined with Mussolini the night before to “discuss tactics”. Although these persist, there is little hard evidence that Italy benefitted from anything other than the home advantage many other hosts have received. Furthermore, the victory came in the middle of a decade of sustained international success for Italy.

Under Pozzo’s stewardship, they won the Central European International Cup (a league competition played over several years) in both 1930 and 1935. In 1936 they won gold at the Berlin Olympics, and two years later, they retained the World Cup in France against a backdrop of anti-fascist protests and hostile crowds. This enabled the regime to legitimately claim it had produced the strongest national football team in the world.

After the second world war, there was some effort to disentangle that sporting success from fascism and to de-politicise the 1934 tournament, but it is patchy. “De-fascistisation happens in different ways in different places,” says Martin. “You’ll see more in Bologna, but in Rome, where the far right tradition has been much stronger, you see nothing.”

Italia 90 used several of the same stadiums, some of which, such as those in Bologna and Florence, had their names changed to remove links to fascism. However, Rome’s Foro Italico sports complex, which includes the Stadio Olimpico where the final was held, still features several fascist mosaics and a huge marble obelisk into which the words “Mussolini Dux” (Mussolini Leader) are carved.

Ninety years on, the shadow of Il Duce still looms large over Italy’s early football success.