In East Berlin in 1988 there was a scramble for concert tickets that made the Oasis reunion price hiking scandal – subject to an ongoing Competition and Markets Authority investigation – look tame.

For one night only, British dark synthpop act Depeche Mode would be appearing at the suitably grim Werner-Seelenbinder-Halle, a former cattle market and slaughterhouse, for the jarringly staid occasion of an anniversary concert for the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ), the state youth movement. It was the first time the band had appeared in the GDR – western acts were largely banned – and, as far as their legions of East German fans knew, it could be the last. Demand for the 6,000 tickets was dangerously intense.

Although the tickets had been given away to schoolchildren, with outstanding FDJ members to be favoured (politicians’ Taylor Swift freebies are nothing new), even in a communist planned economy market forces ruled, and for a short time they became the hardest currency there was in East Berlin. The true meaning of “dynamic pricing” was seen as tickets were traded for as much as six months’ salary, or swapped for state-issue Trabant cars. There may have been a 15-year waiting list for the tinny, two-stroke “Trabis”, but this concert was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“I was lucky enough to get a ticket for a lot of money on the black market,” says Sascha Lange – then a 16-year-old schoolboy living in Leipzig. Now a historian of youth resistance to the Nazis, Lange has just published Depeche Mode Live (Blumenbar), an encyclopaedia of the band’s tours, and his third book on the band written in collaboration with collector Dennis Burmeister.

The book tells the story of the historic East Berlin concert, with interviews with those who made it happen. But it also reveals how Depeche Mode began their takeover of German hearts and minds on the other side of the Wall four years before, exactly 40 years ago.

As 1984 dawned, Depeche Mode were poised for domination in West Germany. They had been slowly creeping up the charts and played more dates there than anywhere else except the UK on their 1983 tour.

Their December 1983 West Berlin show had to be moved to a larger venue – the Deutschlandhalle, built for the 1936 Olympics – to keep up with demand. But the next year, things shifted definitively. “From 1984 on, we really encountered a sort of mass hysteria at Depeche Mode shows,” Gaby Meyer, who worked for the band’s West German concert promoter, says in Depeche Mode Live. “The halls were packed with teens who were beside themselves.”

The band’s “heartthrob” status, exploited ruthlessly by pop magazines like Bravo, played a large part in this frenzy, but the music was not inconsequential either, and the release of People Are People in March 1984 was the moment Depeche Mode became true superstars in West Germany. “The sound was very fresh and exciting,” Lange recalls, and the harsh metallic crashes and synth-manipulated samples were an approach the band had developed while recording in West Berlin (the band’s Martin Gore, a German speaker, had actually moved there). The single shot straight to No 1 in West Germany.

Perhaps crucially, the song’s use of personal relationships as a clumsy metaphor for geopolitical ones seemed to speak directly to a divided Germany (“People are people so why should it be/ You and I should get along so awfully?”) The video’s images of Red Army soldiers and peace marches meant the song was quickly interpreted as being anti-cold war, and when it was used as the theme for West German TV’s Olympics coverage that summer, an event that East Germany boycotted, that impression intensified.

August’s Master and Servant (S&M as a metaphor for capitalism…) was a No 2 hit, and September’s LP Some Great Reward shot to No 3. An appearance on the legendary Thommy’s Pop Show and the making of their first concert film, The World We Live In and Live in Hamburg, crowned the year that Depeche Mode truly arrived in Germany.

While West German fans lapped up everything the free market could offer, their East German counterparts had to be more resourceful. Depeche Mode records were not available at all until state label Amiga finally issued a “greatest hits” in a limited run in 1987, and the occasional coverage of the band in the state-controlled magazines Neues Leben and Melodie und Rhythmus hardly satisfied fans’ appetites. A vigorous black market in photocopied posters and taped West German radio broadcasts developed and unofficial fan clubs proliferated, despite the Stasi monitoring such “subversive” activity.

“For East German and eastern European fans, Depeche Mode were doubly inaccessible in the 1980s,” says Lange. “They were superstars and shielded by bodyguards, and they were on the other side of the iron curtain. That’s why the love for the band was characterised by longing and fantasy.”

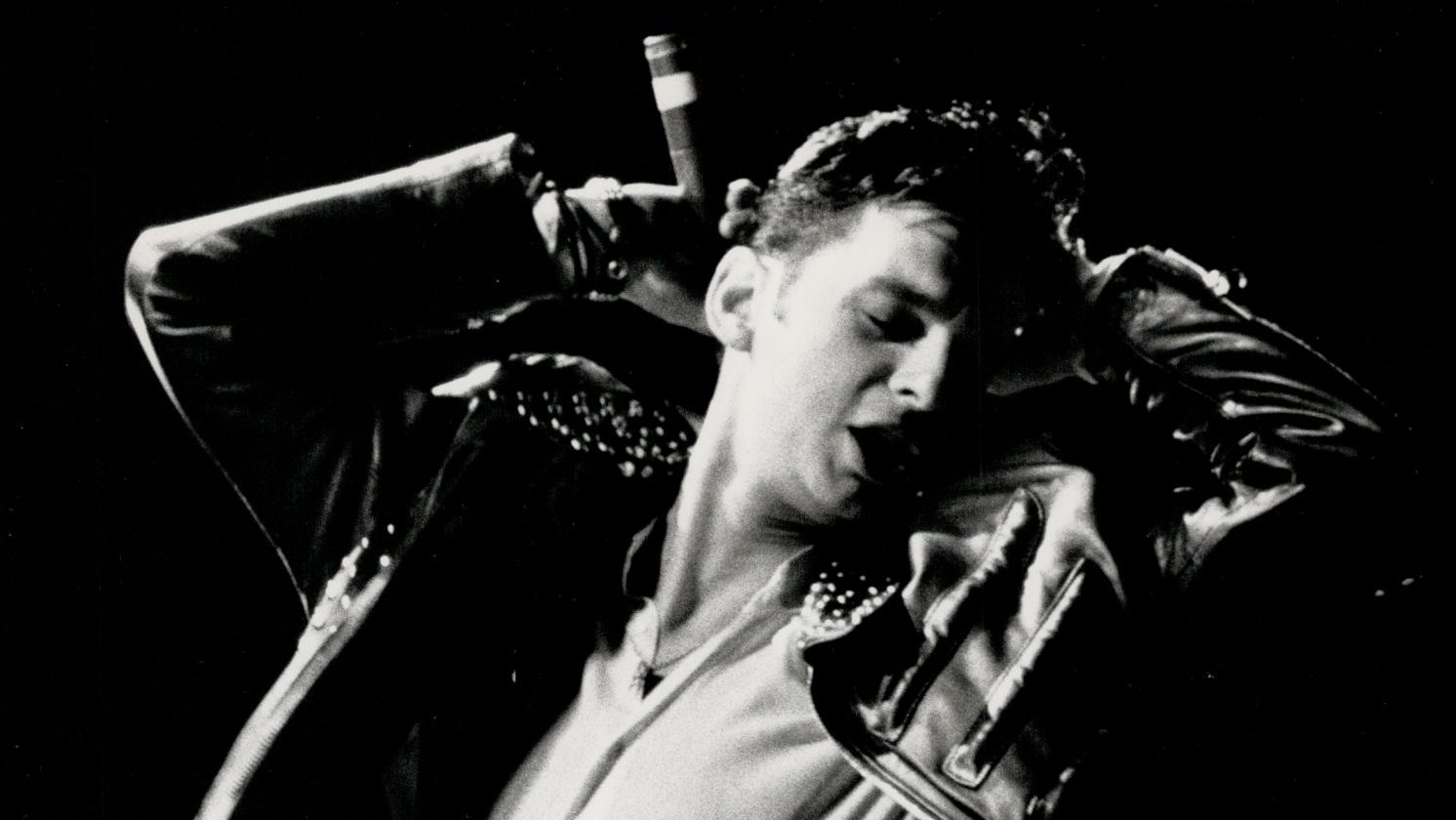

This “fantasy”, he argues, was played out by fans making themselves into Depeche Mode clones. “That wasn’t as pronounced in western Europe as it was in the east,” Lange says, and he speaks from experience – his previous book, Monument (2013), included a picture of a teenage Lange with spiked hair and a leather jacket in a convincing approximation of frontman Dave Gahan’s look.

Fans in the GDR could trace the band’s evolving style through West German music shows like Peter’s Pop-Show and Formel Eins, which could be picked up across the border. “You saw the band dressed up and Dave dancing,” Lange says, “It was all very inspiring, and you quickly identified with the four guys.”

East Germans could also identify deeply with Depeche Mode’s Socialist Realist-inspired aesthetics – sickles, sledgehammers, megaphones – while being thrilled by their subversion through “decadent” western pop. By the time of the East Berlin concert on March 7, 1988, the band were using a set design intended to reflect a totalitarian propaganda rally, and the fantasy crashed into the reality of life in a one-party state.

“If you knew the right places to cross the iron curtain and how to cross, the little presents you should give, it was quite easy to get through,” Berlin-based Hungarian concert promoter Laszlo Hegedus says breezily in his interview for Depeche Mode Live. He had successfully taken the band to Budapest and Warsaw back in 1985 when he began spearheading efforts for the East Berlin concert.

While a relaxation in cultural policy had followed David Bowie’s famous 1987 West Berlin concert, where thousands congregated on the eastern side of the Wall to listen, Hegedus still had to face tortuous negotiations with cagey officials – “If I put 100,000 tickets on the market, 100,000 tickets would be sold out in two days. But the government officials were too scared of that. They kept the show secret.”

Lange heard the rumours three days before the concert. “Of course I didn’t believe it,” he tells me. “It was completely unimaginable that Depeche Mode would ever play in the GDR.”

But, with a teenage recklessness, he made the 90-mile journey anyway – “I absolutely had to be at the concert. So I took the train to East Berlin on my own.” Meanwhile, having made it through Checkpoint Charlie, the band themselves were enjoying the questionable luxury of the official Communist Party hotel, which for all its marble, mahogany and free-flowing champagne could only offer goose fat and bread for dinner. They didn’t even stand to make anything on the gig, paid a paltry fee in worthless East German Marks.

But the band were consoled by the dedication of their fans, who congregated outside the hall in their thousands, despite knowing they were highly unlikely to get in. Lange confirms: “The whole city was full of Depeche Mode fans, complete strangers greeted each other, there was an anticipatory tension in the air.”

He still retains his sense of wonder about that night: “The concert itself was simply incredible. It was as if aliens had landed.” An East German newspaper headline described it in terms of a miracle, saying “The posters came from the walls” and came to life. For East German fans it was a magical moment of communing with idols who represented a glamour and a freedom that was otherwise absent from their lives.

When Depeche Mode returned to Germany in the autumn of 1990, both they and the country had been irrevocably changed. The band had broken America, finding a huge success that would soon turn sour amid addiction and acrimony. The Wall was gone, but German society had hardly begun to heal.

Some argued the band had a hand in the fall of the Wall – Dan Silver, the band’s booking agent, who was in Berlin in November 1989, says in Depeche Mode Live that “Music and Depeche Mode had some influence on these events.”

What was undeniable was that the love for Depeche Mode persisted across a reunified Germany, seen in both their record and ticket sales over the following three and a half decades.

It endures to this day, just as the band itself does despite the sudden death of founding member Andy Fletcher in 2022 (Lange’s book is dedicated to “Fletch”). The 112-date Memento Mori World Tour, which finished in April, included a whole slew of German dates and two sold-out nights at Berlin’s 75,000-capacity Olympiastadion.

While the presenter of 1980s West German pop shows Peter Illmann suggests in Depeche Mode Live that the band’s “certain sense of melancholy” was the reason for their success in Germany, saying, “maybe that reflects the ‘German soul’ somewhat,” Lange says he cannot explain it fully.

But he is emphatic when he says “the special and lasting thing about Depeche Mode is that today fans from all over the world come together at their concerts. Depeche Mode are a cosmopolitan band, they show that music knows no borders.”

In bringing that energy of unity to Germany, Depeche Mode may have played a bigger part in the country’s history than is yet appreciated.