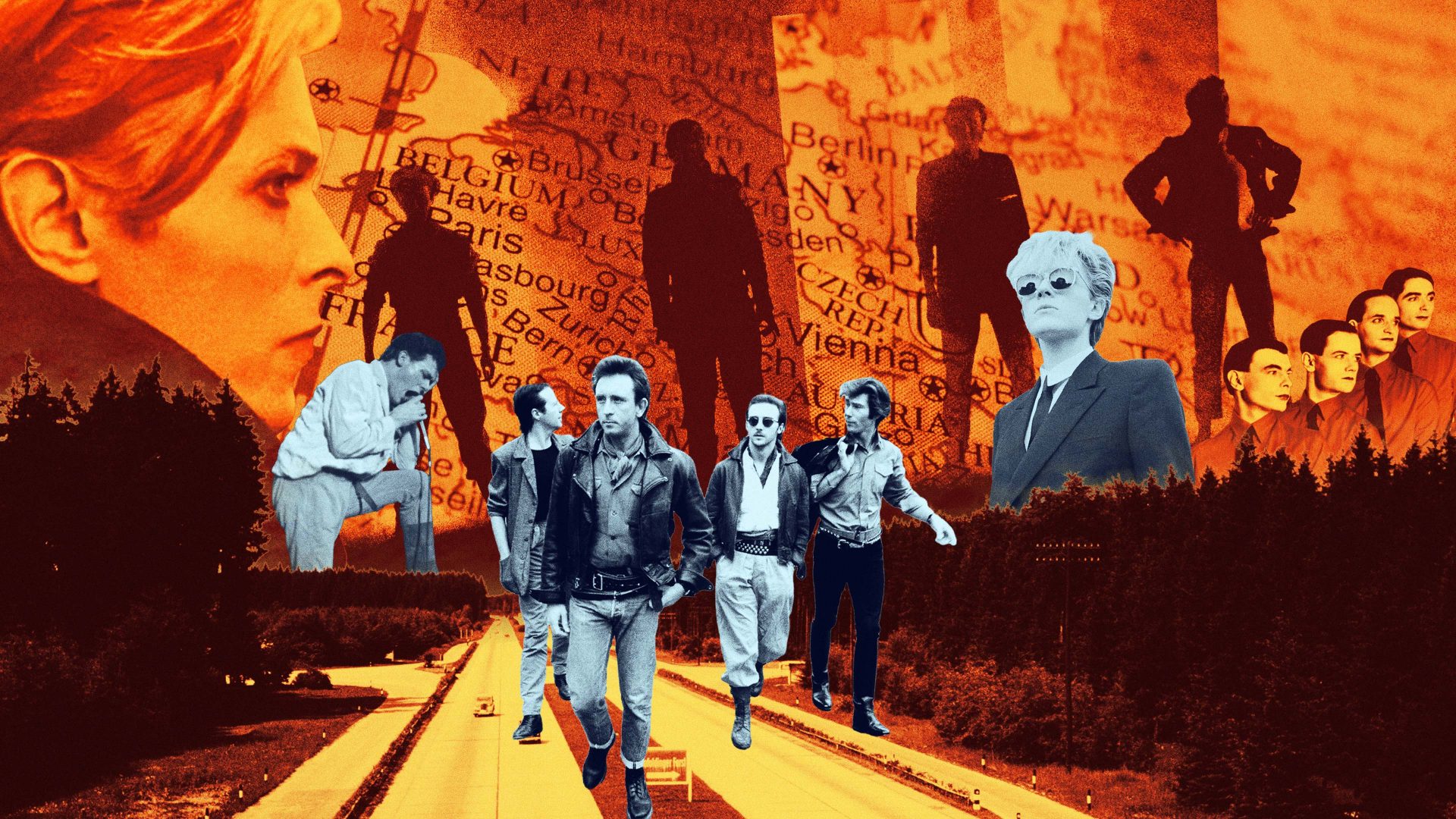

It’s a very definite image: a man in a trenchcoat and a hat, smoking a cigarette, in a city square at night. Around him the air is dark with paranoia and shadows. There are statues. Spies lurk in every doorway and no one can be trusted. Somewhere a woman in a silk dress weeps on a stone bridge, crying: or maybe she’s loading a gun.

For a short time, from the end of the 1970s to the early ’80s, a strange thing happened to British popular music: it went from being fixated on America to becoming obsessed with Europe.

Rock and pop music, which had spent most of the previous decades in jeans and t-shirts, singing about taking its baby to the rock’n’roll dance or driving its Cadillac car down the freeway suddenly dumped its Chevy by the levee and became fascinated with a continent previously known to rock fans as the place that Beethoven was rolling over in.

This was extraordinary: not only (as the Chuck Berry song said) was Europe associated with boredom, stuffiness and a torpid lack of sex, but also it was old, and there was nothing popular music hated more than old (this was in the days before our current era of heritage rock and magazines devoted to listing the achievements of the musical dead).

For generations, teenagers had looked towards the USA for excitement and entertainment: the horrors of British jobsworth culture, as defined by the teen movies of the ’60s, meant that everyone under 21 – which back in the day felt like literally everyone – hated everything old and stuffy and trad, dad.

America had big cars with fins like space sharks: we had Ford Prefects. America had sock hops and soda fountains: we had the youth club disco and newsagents selling Panda Cola. And where the Yanks had Elvis Presley, we had Muffin the Mule.

This continued, in a more bloated manner, into the early 1970s. Led Zeppelin may have been a sort of Godzillabot made of dildos, but they were still, somewhere deep below, an American-style blues band. Even the new glam rockers like the Sweet and T. Rex were recycling American culture with their American riffs. Bands and people alike wore denim, sneakers, and iron-on patches of the American flag in different voices (plain for the rockers, Confederate for the Southern rockers, peace signs for the hippies).

It wasn’t that American culture completely swamped the west – you could turn on BBC Two and, it seemed, watch a European movie almost every night – but it was the case that pop music’s default setting was American.

But then things changed. And by “things”, I mean David Bowie.

Bowie’s impact has been discussed in a million ways: suffice to say that for many teenagers in the 1970s he wasn’t so much a cultural signifier as his own TV channel. Unlike most stars of the era, whose tastes rarely extended beyond the parameters of an NME likes and dislikes column (“Terry Eggs of Fat Jeans likes whisky and can’t stand thin chicks”), Bowie was keen to share something more than his favourite snacks.

Millions of us built entire record collections from Bowie’s endorsements; the Velvet Underground, Iggy Pop, Jacques Brel, Brian Eno: they were like spin-off shows from Bowie’s ongoing drama.

So when Bowie left America to stop being a very American rock star – Los Angeles, drugs, albums with six songs on – and went to Europe, fans listened. And when he made his – QI KLAXON – Berlin Trilogy, in Switzerland, France and, yes, Berlin – several people were excited.

Of course, being Bowie, he wasn’t entirely doing something new, but he was tying up some strands: thinking about Neu! and Kraftwerk as well as cold war paranoia and his own mental state. (The importance of the cold war can’t be underestimated: the presence of the Berlin Wall, the bleakness of Eastern Europe, the thrill of spy fiction and the constant threat of nuclear annihilation were all a lot more stimulating than dancing at the high-school hop)

And shortly afterwards all hell broke loose. New groups were forming all the time in the late 1970s: but punk, while fun, wasn’t very innovative, and a bit of a cul-de-sac. A lot of young musicians wanted to count past three and do something different: the so-called post-punk bands were looking for new places to be. They listened to Bowie and the records he made in Europe, solo or with his travel buddy Iggy Pop: and, because they were rejecting the denim hell of 1970s America, they turned to Europe for ideas.

There had been hints in the past: Kraftwerk had, somehow, had a novelty hit with Autobahn (a song in German with no guitars on it), Lou Reed had recorded an album called Berlin, and something with the none-more-British-’70s name of “krautrock” had gained some publicity thanks to Richard Branson’s Virgin Records label: but Europe and popular music were in the main associated in the public mind with something less mind-expanding.

In the 1970s, package holidays became common. Cheap flights and cheaper hotels meant that, for the first time, millions of deeply insular Brits were going to Europe (America was still out of most people’s price range).

While this was itself an insular experience – the resorts were generally isolated from the host nations like occupying barracks – the new experience began to seep into our monoculture. And not just in the form of model bulls or bottles of retsina: the real home invader was Europop. Sylvia’s Y Viva España, Demis Roussos’s Forever and Ever, and – via Eurovision – the juggernaut that was ABBA all shifted the focus of pop away from America to Europe.

Naturally, it was all still contained by the racism of 1970s media, a culture that maintained Britain had won two world wars and one world cup singlehandedly, that European cooking was “foreign muck” that gave you diarrhoea, and that anything European was either funny or crap: but by 1977 imagined British superiority was tempered with actual experience. People went abroad, and liked it.

And by 1977 a new kind of travel was open to British musicians: touring. With American tours logistically and financially prohibitive, many new British acts found themselves going around Europe: and, with those new Bowie albums on the tour bus stereo, they began to absorb a new world. Bands like Ultravox, Japan and Simple Minds were visiting Europe, listening to Low and The Idiot, and taking in the culture.

For young men and women barely out of their teens, the real Europe was an eye-opener. Here were nations making music and movies the equal of Britain and America’s, with different perspectives, and better food. There was an appealing intelligence at play, a connection between art, pop, culture and popular culture.

It changed people. Simple Minds’ keyboard player Mick McNeill said of that band’s European tour: “We were bedding into the culture, because we were clubbing it every night and having a brilliant time. We’d be listening to Grace Jones or something funky in a German nightclub and thinking: ‘I really like that’. Then you go back home and it obviously starts to bleed through.”

The band’s producer John Leckie confirmed: “That European tour was a big thing. They were attracted to it. The Beatles, rock’n’roll, American country, Johnny Cash – forget all that. Europe was the future, the way forward.”

Back home, bands were going to London’s Blitz club, Birmingham’s Rum Runner and others, dressing up, dancing to Kraftwerk, forming their own bands and listening to new records. Japan’s European Son, Ultravox’s New Europeans, Landscape’s European Man. John Foxx’s Europe After the Rain, Roxy Music’s A Song for Europe, Psychedelic Furs’ Sister Europe, the Skids’ Days in Europa. The Mobiles’ Drowning in Berlin, Japan’s Suburban Berlin. The Korgis’ Young and Russian, Telex’s Moskow Diskow. They Must Be Russians, Spandau Ballet, Alphaville, Warsaw (later Joy Division).

A theme was emerging. People were dressing up in trenchcoats, smoking cigarettes and making videos of themselves dressing up in trenchcoats and smoking cigarettes. By the time Ultravox released Vienna, Europe was, as Kraftwerk had said, Endless.

For a while Top of the Pops looked like auditions for The Third Man: and, for a while, pop and Europe made something exciting and new: but pop never stays in one place for long. Soon the new bands were touring America and, shortly afterwards, sounding American (Simple Minds wrote a song called The American: U2 bought cowboy hats). MTV came along and offered fame to anyone whose hair was shaped like a bird. The cold war ended: the Berlin Wall came down. The 20th century ended, and David Bowie released a new song, Where Are We Now?, a gorgeous reflection on the passage of time, seen through the lens of his time in Berlin.

The echoes of the European fixation are still out there, in records like the Manic Street Preachers’ Futurology, in TV shows like Deutschland ’83 and Kleo, and in the work of Europhile novelists like Jonathan Coe. Popular culture and pop music may have moved on, but these things go round and come around again.

Until then, as Humphrey Bogart nearly said, we’ll always have Berlin.

Emmy-winning writer David Quantick is co-host of The Old Fools podcast