The final song on the final album by David Bowie – a man who had made a profession out of hiding behind a series of personas – was one that underlined his career-long guarding of his privacy. Signing off with I Can’t Give Everything Away, with the idiomatic meaning of that title and

cryptic lines like “With skull designs upon my shoes”, seemed a typically

impish joke at the public’s expense when Bowie died two days after the album was released, having kept his terminal illness a secret from us all.

But that wistful song could also be interpreted as genuinely plaintive, a cry from one of the most famous people in the world and one of the most flamboyant showmen ever, that he was, in the end, just a man and could not completely deplete himself for public consumption.

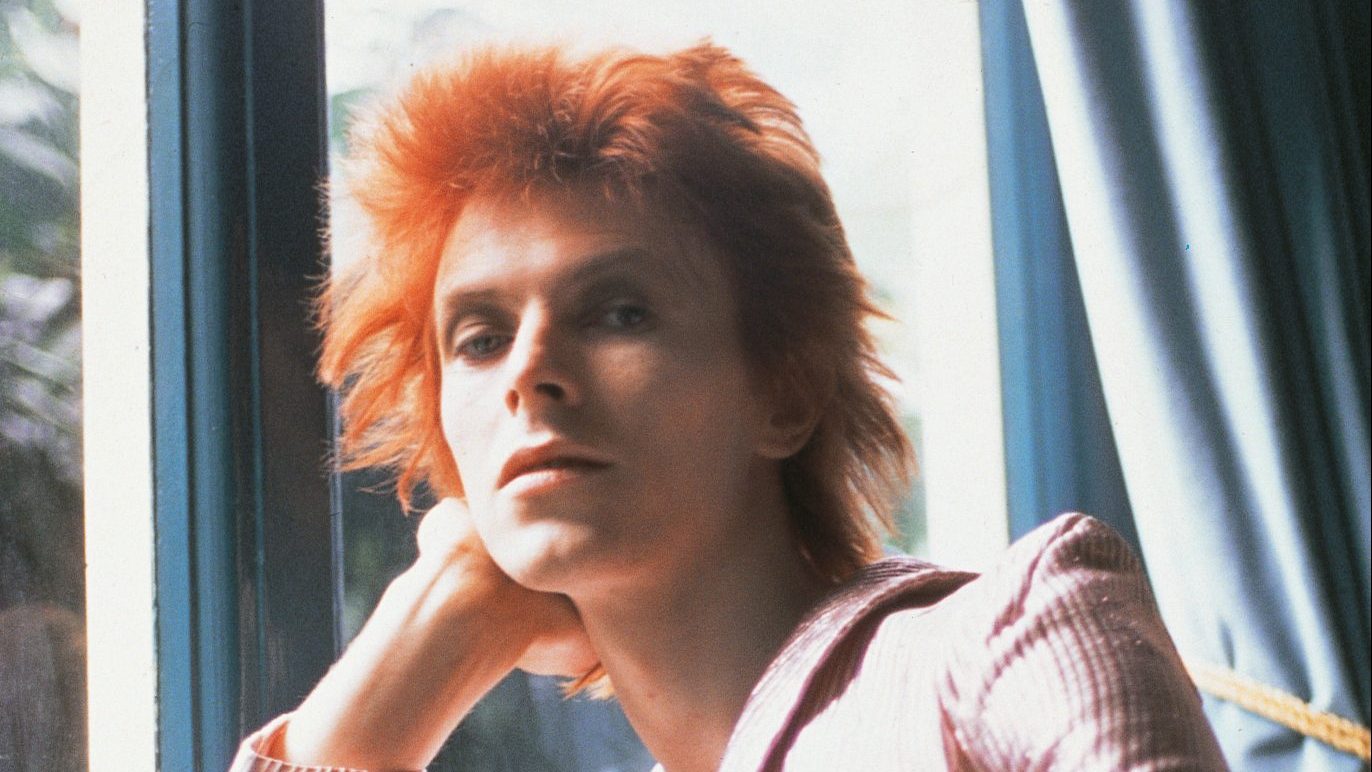

Bowie’s guarding of his privacy and lack of loquaciousness about his work is what makes Moonage Daydream: The Life and Times of Ziggy Stardust, a new

edition of the book Bowie produced with the legendary rock photographer

Mick Rock in 2002, so significant. A running commentary from Bowie accompanied the more than 600 photographs taken by Rock during a

20-month period in 1972-73 – ranging from now-famous portraits to less

commonly seen homespun early photo shoots and candid on-tour shots. Rolling Stone called it “the closest we’ll ever get to a straight-up Bowie autobiography”.

Twenty years on from the much-coveted, signed limited edition of the

book, 50 years on from the birth of Ziggy, and with both authors no longer

with us (Rock died late last year), this new edition is a tribute in multiple

ways. Rock also admitted, “I’ve learned a lot that I didn’t glean at the time about the whole crazy affair.”

But Bowie’s text is hardly some confessional exercise provoked by late-career anxiety about his legacy. In a nonchalant foreword, he makes the

limits of his remit clear: “I’ll go on a bit about individual photos. It is not intended to be autobiographical (that would be an entirely different book) or

particularly chronological; it is more a series of impressions based on the photos themselves.”

But even if Bowie pulls away from the task before he has even begun, and his text is indeed scant and patchy (for example, we get a comparatively meaty paragraph on the recording of just one single with Lulu, but disproportionately brief mentions of working on whole albums in this period with alternative icons Lou Reed and Iggy Pop), the very off-the-cuffness of Bowie’s commentary reveals something about the man behind the on-stage mask.

Bowie is hugely generous in giving credit to those who helped to shape the Ziggy image, right down to Stan “Dusty” Miller of Greenway and Sons

bootmakers, Penge, who made the red vinyl platform boots key to the early

Ziggy look. He also writes with great affection about Mick Ronson, the guitarist without whom Ziggy wouldn’t have rocked nearly as hard.

Almost as affectionate is his brief account of his developing love affair with America in these crucial years, writing of discovering the US on tour via Amtrak trains, saying they “gave me an original and intimate way of finding the country I was being more and more drawn to living in”. He would later live in the US for over two decades and die in his beloved adoptive home of New York.

Moonage Daydream also confirms Bowie’s fondness for slightly surreal humour. “So many hotels, so much flock wallpaper. On many occasions,

having dressed for the show, I would be virtually indistinguishable from my

rented surroundings,” he writes of a series of pictures of himself donning his stage trousers in a chintzy Chicago hotel room.

As, page by page, we see the Ziggy image evolve before our very eyes, Bowie’s apparent inability to take that image seriously (“Daft? You bet”, he comments) cuts through the iconicity of the photographs so this is not the dully reverent document of a seminal cultural moment it could have been, but a meeting between a 25-year-old man at the outset of a stellar career and his older self on the other side of that career – as he puts it, “from way over here” – having kept so much to himself to the very end.

Moonage Daydream, by David Bowie and Mick Rock, is available from all

good bookshops. Order online at www.BowieBook.com

BOWIE AND ROCK’S MOONAGE DAYDREAM in five songs

Moonage Daydream (1971)

Bowie’s darkly erotic song summed up his manifesto for the Ziggy era,

inspired in large part by Kubrick’s futuristic and visceral visions in 2001

and A Clockwork Orange, and recounted in the book: “the Seventies were the start of the twenty-first century… everything was up for grabs.”

Ziggy Stardust (1971)

The song that told the story of Bowie’s Ziggy character offered some clues about that character’s many influences, from kabuki theatre (“Like some cat from Japan”) to British rocker Vince Taylor who developed a Christ complex as his mind and career slipped away (“Like a leper messiah”).

Starman (1972)

On July 6 1972, less than four months into Rock’s stint as Ziggy’s official

photographer, Bowie performed this hit on Top of the Pops, crashing into

the British public’s consciousness.

Cracked Actor (1973)

A stand-out moment of the follow-up LP to Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane

(1973), Bowie is vague in his recollection of writing this song during the US leg of the Ziggy Stardust tour in the book, but its picture of Hollywood decadence clearly referenced the seedy spectacles he encountered in Los

Angeles.

Lulu, The Man Who Sold the World (1974)

Despite working with Lou Reed and Iggy Pop in his Ziggy period, Bowie

chooses to heap effusive praise on this more unlikely collaboration in the book, writing “Lulu is such a bright, funny and talented little thing”, adding “I still have a very soft spot for that version.”