“The #MeToo movement is an example of social change but it is also a test of it. In this fractured environment, will all of us be able to forge a new set of mutually fair rules and protections?” This is the question posed by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey in She Said, their bestselling account of the New York Times investigation published in October 2017 that brought down Harvey Weinstein and launched a global movement against sexual harassment and assault.

It also offers the best moral framework within which to understand the Huw Edwards story and the extraordinary sequence of allegations and counter-allegations that led to the naming of the veteran broadcaster on the BBC’s Six O’Clock News last Wednesday.

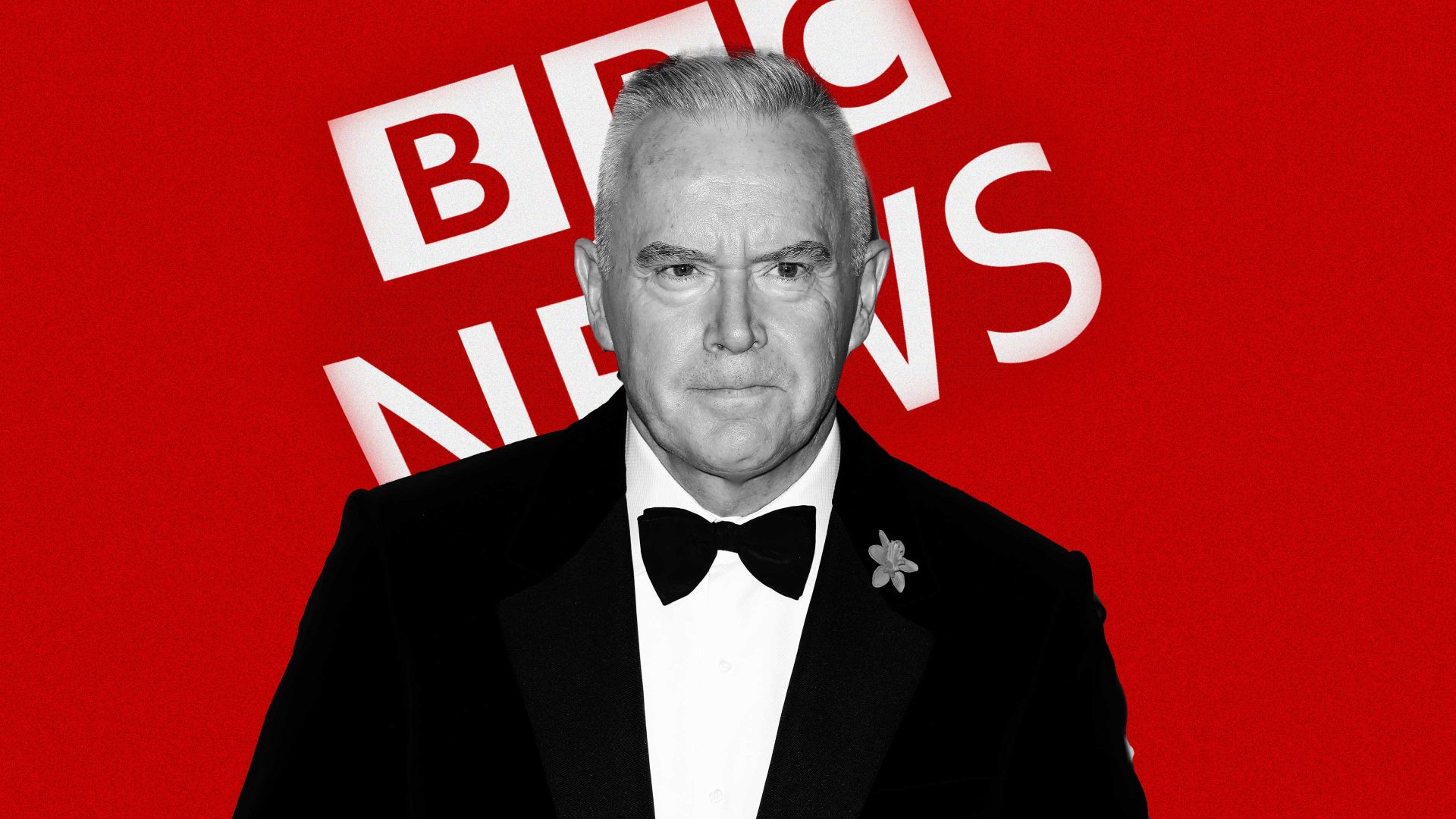

Because the claims of sexual impropriety by the 61-year presenter – initially unnamed – first appeared in the Sun on Friday, July 7, the whole drama has primarily (and inevitably) been presented as a battle between Rupert Murdoch’s empire and the Beeb. But, important as that battle undoubtedly is, it is not the heart of the matter.

As I say in the latest episode of The Two Matts (the weekly podcast in which TNE founder and editor-in-chief Matt Kelly and I chew over the news: do please tune in), the initial response to the statement by Edwards’ wife, Vicky Flind, troubled me. No sooner had the identity of the hitherto-unnamed presenter been established than the wagons were circled around him by a series of distinguished and powerful media figures.

Much of this response, without question, was driven by sincere affection and regard for a man who, it was revealed, had now been hospitalised with mental health issues. But it also centred on Edwards himself and his personal psychological predicament and left little if any space on the stage for the alleged victims: of whom, by then, there were at least six. Unusually in such circumstances. Flind’s statement made no mention of them at all, beyond a very general request that the privacy of “everyone else caught up in these upsetting events” be respected.

Time and again it was said in the presenter’s defence that he was “complicated”. Well, indeed: most people are. But they don’t all inflict their complexities, neuroses and foibles upon the young and the vulnerable. Do they?

Time and again, it was hammered home that the Met and the South Wales police had announced that they had identified no evidence of criminality – as if that were an end to the matter.

But the core argument of the #MeToo movement in 2017 was precisely that illegality is not the only test of improper conduct. As the great feminist campaigner Catherine A Mackinnon wrote in the New York Times in February 2018, it was “accomplishing what sexual harassment law to date has not”.

Leave aside the case of the first alleged victim, in which the young person in question denies the version of events recounted by their parents to the Sun. The BBC itself reported last Tuesday that a second individual in their early twenties had allegedly been sent “abusive, expletive-filled messages” on a dating app by the presenter and remained scared by these threats.

As the week progressed, further claims emerged: that a 17-year-old had allegedly been messaged on Instagram by Edwards, using hearts and kisses; that he had allegedly broken lockdown rules in February 2021 to meet a 23-year-old in their flat and had given them £600; and that two current BBC employees alleged that they had received “inappropriate” messages. One of them used the words “cold shudder” to describe their response to his alleged comments on their physical appearance. “There is a power dynamic that made them inappropriate,” the other said.

Another former employee of the corporation alleged that they had received messages from Edwards, “some late at night and signed off with kisses”, which they characterised as an “abuse of power”.

Disparity of power has always been the principal preoccupation of the #MeToo movement. Two of the three alleged victims whose claims were reported by BBC Newsnight spoke of “a reluctance among junior staff to complain to managers about the conduct of high-profile colleagues in case it adversely affected their careers”. Such anxiety will be familiar to anyone who has followed the hundreds of cases reported since Kantor and Twohey’s initial story about Weinstein.

The BBC’s claim to be meticulously attentive to its “duty of care” has scarcely been bolstered by the unconscionable seven-week delay between the initial complaint lodged by a family member of the alleged first victim and action being taken. How, one wonders, will the other young people involved in this case – some of whom have made allegations to media organisations that are not yet public – have felt as they watched the powerful line-up beside Edwards on Wednesday night and their own experiences eclipsed by furious attacks on the Sun. How much trust will they have in the conventional procedures, protocols and tribunals that govern such investigations?

Just as free speech is meaningless unless you allow speech you don’t like, the rules governing sexual conduct are pointless if nice guys get a free pass. Weinstein resembled a central-casting predator, as did Jimmy Savile. Edwards looks as though he has been genetically engineered to be a National Treasure. But so what?

It is perfectly possible to object to the Sun’s reporting and the anti-BBC agenda of the Murdoch press, and to recognise that there is, at minimum, prima facie evidence here of a deeply disturbing pattern of behaviour.

Edwards has yet to address the reports of this pattern. One wishes him a speedy recovery, not least so that he has the chance to answer in full the allegations made against him. But we should also hope that the alleged victims will feel able to testify freely in the BBC’s internal investigation. When the powerful cluster to protect one of their own, faith in justice suffers. All that we know for sure about this sorry saga is that justice has yet to be done.