Five days after the referendum, Nigel Farage returned to the European parliament to paraphrase Bob Monkhouse’s most famous line, telling its president, Martin Schulz: “When I came here 17 years ago and said that I wanted to lead a campaign to get Britain to leave the European Union, you all laughed at me. Well, I have to say, you’re not laughing now, are you?”

Brexit itself is definitely no joke. Yet in the six years that have followed the referendum vote, many have found some dark humour in watching the progress of those responsible for it.

Like some Brussels-backed update of the Curse of Tutankhamun’s tomb, Brexit seems to have cast a dark shadow over all those who encounter it. True, some may be considerably wealthier than they were six years ago, and one is (for now) resident in 10 Downing Street. But none is as popular, as listened to as they once were, probably because none can pretend that Brexit has turned out quite the way they sold it.

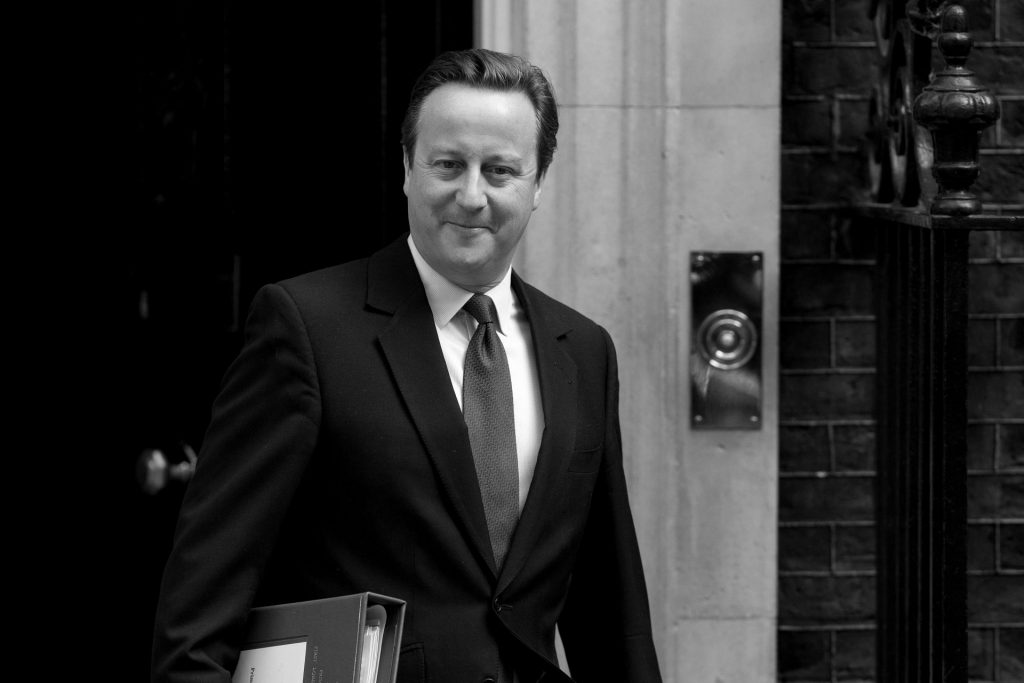

You didn’t even have to think Brexit was a good idea in the first place to have been touched by the curse. Two prime ministers have buried themselves over it; David Cameron, who fancied the hat-trick after referendum wins over PR and Scottish independence, and Theresa May, whose disastrous 2017 snap election campaign in search of a mild-Brexit majority left her at the mercy of bitterBrexit zealots. Both have cashed in since leaving office – Cameron with £7m from Greensill Capital before it collapsed, £2m from the lecture circuit for May – but neither are embraced as wise old heads, as Sir John Major and Gordon Brown now are.

Of those who were true believers from the start, none have had bumpier rides on the post-referendum rollercoaster than the “bad boys of Brexit”, the self-awarded, self-aggrandising nickname for those at the top of the unofficial Leave campaign. They might have considered June 24, 2016 to be an all-time high, but by November that year they were even higher – several dozen floors above Manhattan, in fact, as Ukip leader Farage, Leave EU’s multimillionaire insurance broker backer Arron Banks and his henchman, Andy Wigmore, were photographed in a Trump Tower gold lift with the president-elect. Could they get higher still?

Farage certainly held loftier ambitions. Declining a £250,000 offer to appear on I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!, he was proposed by Donald Trump as Britain’s ambassador to the US – for once, a piece of bad advice that May declined to take – and touted for a knighthood. He finally got one, but only in a comedy segment on the now-banned Russia Today channel.

Meanwhile, Farage’s on-off relationship with Ukip continued, until he finally left the party for Gerard “Batty” Batten to lead it into obscurity. Though protesting he was “skint” after a marital split, he continued to be funded by Banks, who stumped up £450,000 in the year after the referendum, including for the rent on a Chelsea townhouse. Banks himself dabbled in Ukip politics, but amid unwelcome publicity he was gradually replaced as a Brexit frontman by his Leave.EU co-founder Richard Tice, a property tycoon.

Along with John Longworth, the former director-general of the British Chambers of Commerce, Tice set up Leave Means Leave, the campaign group for a hard Brexit, which held dozens of big rallies with Farage front and centre from late 2016 onwards.

One reason for Banks’ absence may have been that Tice was concerned about the impact of a National Crime Agency investigation – Banks was referred to the agency by the Electoral Commission after Leave.EU was fined for breaking electoral law during the referendum, but it ultimately found “no evidence” of criminal offences.

Banks and Wigmore later worked on campaigns for the nationalist New Zealand First party in New Zealand, quickly demolished in a general election by Jacinda Ardern.

Back at home, while May struggled to articulate and then pass her own version of Brexit, and support for a second referendum surged, Farage and Tice hurriedly turned Leave Means Leave into the Brexit party, ready for the 2019 European parliament election. “It was Nigel and my decision who stood where and in what order,” said Tice, and as such, he was first on his party’s list in the East of England constituency and was elected as one of its three MEPs there. The Brexiteers won 29 of 73 seats, taking 30.5% of the vote – over double what the Conservatives polled – and May resigned before the full results were even known.

This might have been the moment of supreme opportunity for Farage but instead, as Boris Johnson became prime minister, he found himself out-Brexited. At the December 2019 general election, Tice and Farage stood candidates down in 317 Tory-held seats and received 644,257 votes, just 2% of the national total. There was renewed speculation about secret deals and knighthoods, but Farage insists he elicited from Johnson only a pledge to get a hard Brexit done – one that he considers has been broken.

The Brexit party became Reform UK in October 2020, and Tice succeeded Farage as leader in March 2021 (both iterations of the party have no members, but “registered supporters” who have no democratic say in its organisation). Since then he has stood for election twice, taking 3.1% of the vote in the Havering and Redbridge seat in last year’s London Assembly election and 6.6% in the same year’s Old Bexley and Sidcup byelection. Neither result, nor Reform’s slide to obscurity, has prevented his every utterance being reported breathlessly by the Daily Express.

Farage has scrabbled for a role. He spent, and spends, a lot of time monitoring the Kent coastline, looking for migrant-carrying boats for his social media content. Having lost his presenting job on LBC after comparing Black Lives Matters protesters to the Taliban, he re-emerged at GB News (against the resistance of Andrew Neil) where he continues to host a primetime chat show, including a segment called Talking Pints – Farage and a guest talk, while drinking pints. And finally, the man once talked up as a possible ambassador to the US by the president also sells personalised video messages on the website Cameo. £75, since you ask.

Farage’s promises about what Brexit would mean continue to turn to dust. Days after the referendum was won, he predicted Denmark, Italy, Poland and perhaps even France would now exit too in a “total reconfiguration of what Europe is all about”. But even before Ukraine, pro-EU sentiment was hardening because of Britain’s example. The once-dominant populist Danish People’s party no longer campaigns for Dexit – a trend that is replicated across Europe, and Marine Le Pen dropped Frexit from the menu during her recent failed attempt to become French president and more successful parliamentary campaign.

Some of the Romanians Farage was so worried about have gone home, but overall migration is up, thanks to arrivals from India, Nigeria, the Philippines and Hong Kong – though these doctors, students and IT workers are unlikely to fill the fruitpicking roles needed in Farage’s heartland, or to help out in the hospitality industry when he craves a pint.

Yet maybe the nation has had enough of the man in tweed. Days after launching a campaign for a referendum against Johnson’s net-zero target, a poll found 60% of British voters supported the climate goal and only 10% agreed with Farage.

Little has been heard about the campaign since, either from Farage or his partner in it, Tice. But perhaps Tice has his hands full as the romantic partner of Isabel Oakeshott, the Brexiteer journalist best known for an unlikely tale of David Cameron and a pig’s head. She often pops up on TalkTV at the same time as Farage fronts his show on GB News.

Wigmore remains a vocal presence on Twitter, where he now describes himself as a hemp farmer. Banks has just lost a libel action against the journalist Carole Cadwalladr, who had investigated meetings between the main funder of the Brexit campaign and the Russian government.

Sadly there is still no news of the £60m film version that was reportedly to be made of The Bad Boys of Brexit, Banks’ account of the referendum campaign. Its publisher, Iain Dale, who had been due to be the executive producer on the film, later admitted he had (“strangely, given I held the rights”) never been invited to any of the meetings.

Perhaps that is for the best when one considers the identity of the man tipped at the time to play Farage when the blockbuster film was eventually made. It was Kevin Spacey.

Fortunes made, reputations lost… it’s the curse of Brexit

DAVID CAMERON

Never actually a Brexiteer, the prime minister who made it all possible immediately resigned and retreated to a £25,000 “luxury hut” to write a poorly received memoir, 50% of which was him slapping himself on the back for transforming the Conservatives into a liberal party comfortable with the modern world. He was mocked by Theresa May for his “wheely shed” and famously accused by Danny Dyer of relaxing “with his trotters up” while the rest of Britain dealt with the consequences of Brexit. Got himself into a lot of trouble working as an adviser to Greensill Capital, lobbying the government to bend rules to allow it to receive Covid corporate financing facility loans before the firm collapsed. More recently has devoted his time to charity work, driving a van containing supplies for Ukrainian refugees to Poland.

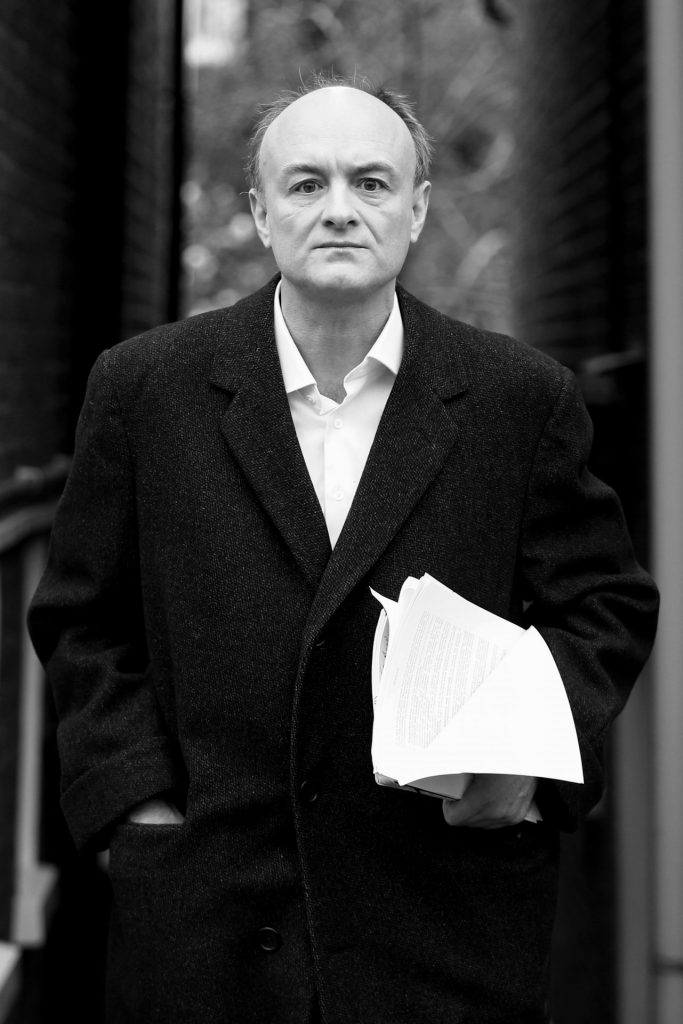

DOMINIC CUMMINGS

A quiet life since the referendum except for: becoming Boris Johnson’s de facto chief of staff in Downing Street and immediately overseeing a reign of terror among special advisers, advising the prime minister to illegally prorogue parliament, running a divisive general election campaign, travelling further in lockdown with coronavirus than Crewe Alexandra have ever gone for a competitive game in their 145-year history, claiming he needed to drive to Barnard Castle in County Durham to test his eyesight, eventually parting with Johnson when it turned out calling his girlfriend “Princess Nut Nut” was the line, admitting in an interview he had discussed ousting Johnson within days of the 2019 election and now seeking to bring down the PM via a paid-for Substack newsletter.

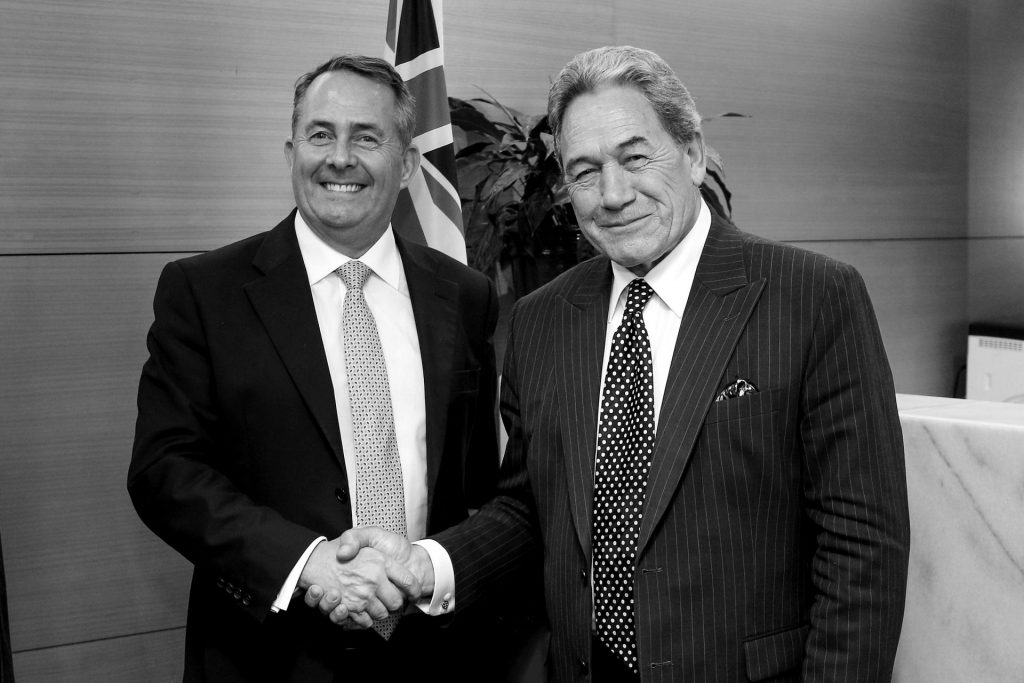

LIAM FOX

The disgraced former defence secretary was also brought back into frontline politics by Theresa May, this time in the new international trade department. Claiming a trade deal with the EU would be the “easiest in human history”, he also endeared himself to business by saying UK companies failed to export enough because “it might be too difficult or too time-consuming or because they can’t play golf on a Friday afternoon”. Fox lost his job when Johnson succeeded May, although the new PM did nominate him as a candidate for director-general of the World Trade Organization. He didn’t get it and remains a backbench MP.

ARLENE FOSTER

Northern Ireland’s first minister – a hardline Brexiteer in a part of the UK that voted 55.8% to remain – had an eventful post-referendum career in which she variously saw Stormont suspended, was removed from office as a result of the so-called “cash for ash” scandal, oversaw a lengthy period of political deadlock, returned at the head of a reformed administration, propped up Theresa May’s administration, withdrew support under Boris Johnson and then was forced to quit after losing the support of her party. Now, like Farage, a presenter at GB News.

MICHAEL GOVE

The ardent Brexiteer immediately turned on his partner-in-crime, Boris Johnson, blowing up his bid for the Tory leadership by saying he “cannot provide the leadership or build the team for the task ahead”, unsuccessfully running himself and then being immediately sacked by Theresa May and told to “go and learn about loyalty on the backbenches”. Surprisingly brought back into government as environment secretary in 2017, he has since served as a Cabinet Office minister and now levelling-up secretary, in which role clever comments he has made in cabinet meetings are routinely leaked to his former employer The Times.

DANIEL HANNAN

The so-called “brains behind Brexit” left the European parliament as the UK formally left the EU in 2020 and, after a political lifetime spent railing against decisions being made by an unelected elite, took his seat for life in the House of Lords as Baron Hannan of Kingsclere, of Kingsclere in the County of Hampshire.

Also named an adviser to the British Board of Trade, the prominent campaigner for the hardest of Brexits raised eyebrows earlier this month when he admitted the UK should have stayed in the EU single market after Brexit, saying it would have saved “a lot of trouble”.

KATE HOEY

The former Labour MP and sport minister became a meme during the Brexit referendum for her Titanic-style poses on a boat alongside Nigel Farage during a pro-Brexit flotilla on the River Thames. After a political lifetime spent railing against decisions being made by an unelected elite, she took her seat for life in the House of Lords as Baroness Hoey of Lylehill and Rathlin in the County of Antrim in 2020. She recently accused those plotting for Johnson’s removal of being motivated by the fact “they don’t like the fact that the prime minister took us out of the European Union”, something that must have come as news to rebels David Davis and Steve Baker. Her dwindling popularity in NI – in 2016 she wrote “Brexit won’t hurt Northern Ireland at all – instead, it will brighten its future” – helped to deliver Sinn Féin’s victory at the recent elections.

DAVID DAVIS

The quixotic backbencher – he resigned his seat in 2008 and sparked a byelection for reasons even he probably struggles to remember – was surprisingly brought into the cabinet by Theresa May as Brexit secretary with the task of negotiating a withdrawal agreement. Thus, having spent his entire political life advocating the UK leaving the European Union, he was personally given the task of delivering it … but it turned out he couldn’t really be bothered.

Pictured early on sitting down to negotiations without any notes, then opining that he didn’t need to “be very clever” or “know that much” in order to be Brexit secretary, Davis lasted two years in the job before resigning, Brexit undone, in protest at Theresa May’s Chequers deal. Now fervently anti-Johnson on the Tory backbenches.