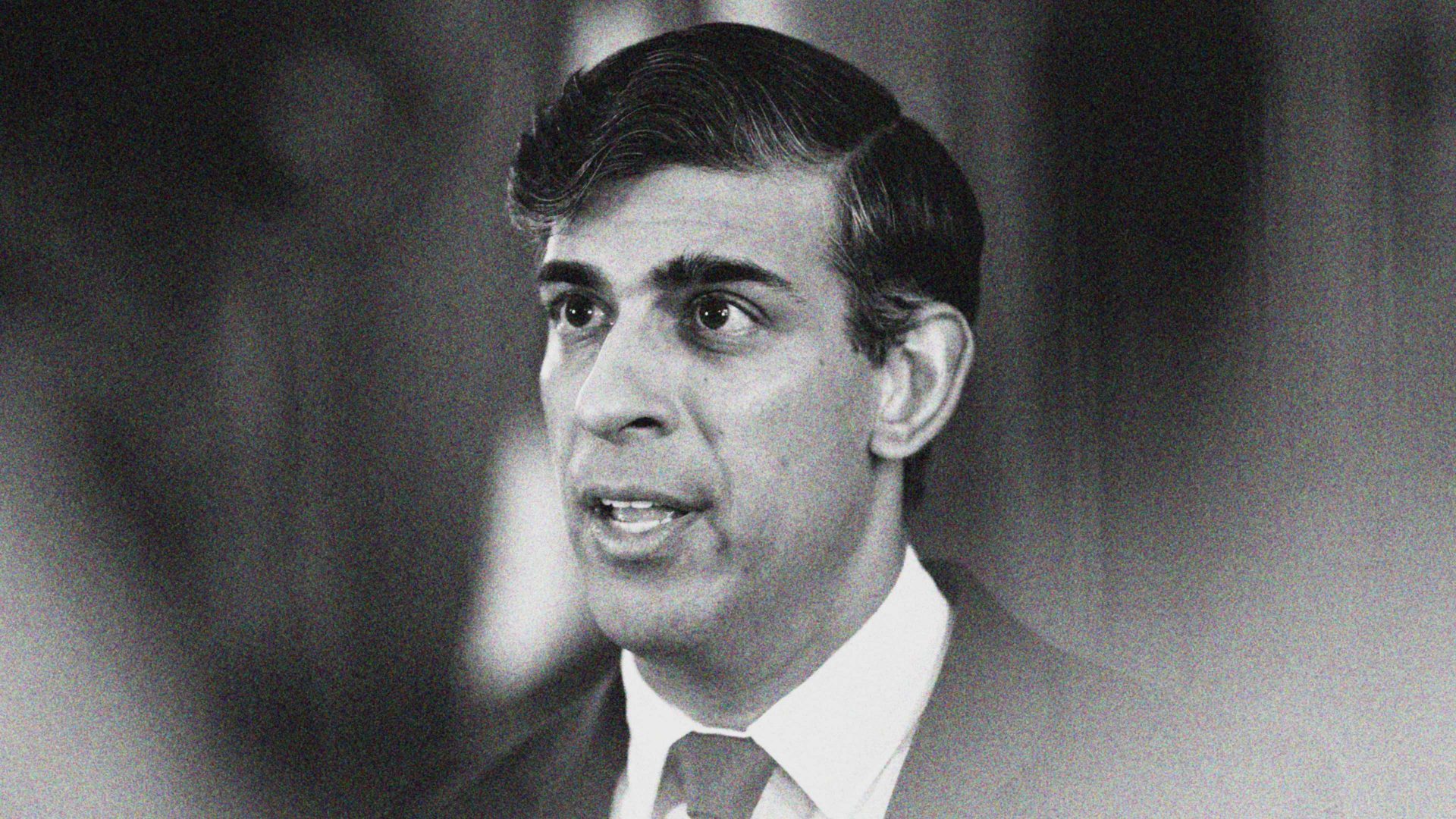

Last week, Rishi Sunak was going – finally – to “turn a corner” and have a good few days, or so Westminster’s journalists were being briefed.

Labour finally had a scandal (of sorts) of its own with Raynergate. And while the Mail and Times continued with the latest developments in a very minor saga, Sunak thought he had some policy wins imminent.

The inflation figures were set to be published, hopefully reinforcing the only one of Sunak’s five pledges that he is actually meeting, while the government was expected to pass two key pieces of legislation. One was the age-ratcheting ban on buying cigarettes that the prime minister had personally pushed so hard; the other was the government’s cynical scheme to send asylum seekers to Rwanda without processing their claims.

Oh, and there was to be a surprise too – a new policy that would stop the public focusing on Sunak’s collapsing government and instead force them to confront those who are really responsible for the country’s ills. Which turned out to be people off sick with depression or anxiety.

None of this might not be many people’s idea of a good week, but when you’re deeply unpopular in your party and the country, any week where you get something, anything good is, relatively speaking, a decent one.

It’s perhaps a sign of the lack of confidence inside No 10 that the “good week” narrative was briefed in advance – advisers may have sensed that the only way anyone was going to write an article with those words was by looking forwards because, predictably enough, the week that actually took place turned out nothing like Sunak might have hoped.

Perhaps the best news for Sunak was that his controversial smoking policy passed, but more on this later. Inflation wasn’t exactly a disaster for the prime minister, but the issue did show the difficulty of trying to make price rises a centrepiece of your offering to voters.

When the official figure came in, it was 3.2% – certainly well down on inflation’s peak as energy and food prices spiked in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But, as commentators had to explain, falling inflation doesn’t mean falling prices – it just means that while things are still getting more expensive, they’re doing so more slowly now. Things getting worse less rapidly is not exactly something to prompt the rapturous thanks of a grateful nation.

Compounding the underwhelming moment is the fact that experts had expected inflation to fall more than it actually did, meaning that there was no big stock market bounce as a result.

There is also the awkward fact for the government that the UK’s official inflation target is 2% – so we’re still well off it. By cutting national insurance twice, the government has put more money into the economy (which boosts inflation) just as the Bank of England is trying to use interest rates to take it out.

So, with his failed tactic of using tax cuts for popularity, Sunak may have ruined any prospect of having the Bank cut interest rates much before he calls an election. Hardly a brilliant start to the “good” week.

That left the PM looking to the Rwanda bill for comfort – though if he had not learned over the last year that Rwanda always disappoints then there is no hope for him. And actually, there is no hope for him.

The House of Lords proved more resilient in its attempts to modify the bill than the government had expected – reportedly their resolve was stiffened by briefing ahead of time that they would fold within the week.

Much of the media reporting suggests the Lords were trying to “block” the bill, but in practice the final stages of the row between the government and peers had narrowed down to two specific objections: peers wanted an independent panel to confirm Rwanda was a safe place to send people, and wanted some specific protections to make absolutely sure no one who helped the UK in Afghanistan would be sent to Rwanda.

Once again, you’re left to wonder what counts as a good day within No 10: to get the Rwanda deal – which involves shipping people, including legitimate refugees, thousands of miles away – you’re left explaining why you won’t put in the most basic of protections asked for by peers.

And once all of that is overcome, you’re going to face months of legal challenges, all to pack some vulnerable people on to a plane for a few front pages.

Next, Sunak’s predecessor, Liz Truss, still a sitting MP in his governing party, did a flurry of interviews to promote her new book – during the course of which she suggested that she’d like to abolish the UN, European Court of Human Rights, Human Rights Act, Environment Agency, Supreme Court, and several other institutions.

Sounding unhinged, Truss helpfully reminded the rest of the country about her disastrous 49-day premiership – and may even have reminded a few people that when Sunak was in a head-to-head contest against this bizarre figure, he lost – heavily.

So destructive was the blanket coverage of Truss that when the truly weird story of Tory MP Mark Menzies appeared in the Times, some wags joked that the whips’ office might have put it out just to get the media to talk about anything except Truss.

It is perhaps a sign of how inured we have all become to Tory chaos that the Menzies farrago has almost been greeted with an accepting shrug. The Times story – many elements of which are denied by Menzies’ team – includes allegations of using campaign funds to secure the MP’s 3am release from “bad men”, spending tens of thousands on “personal medical expenses”, getting a dog drunk, and more.

A scandal-weary Westminster almost immediately started wondering how long it would be until the next, surely inevitable, by-election – though for now Menzies has just relinquished the Conservative whip and says he is standing down at the next election.

Lest there still be any question as to whether Sunak and his government had truly turned the corner, it was answered fairly definitively by Ipsos Mori when they published a poll showing Labour on 45% and the Conservatives on just 19%.

This was a disaster just days ahead of crucial local elections in which the party is set to lose half of the council seats it is defending, and in which two crucial mayoralties are at risk. If Andy Street loses the West Midlands and Ben Houchen loses Tees Valley, Tory MPs might go feral once more and depose yet another leader.

Sunak’s crackdown on people too ill to work is unlikely to convince Tory waverers, even if it does play to the party’s traditional narrative that it is benefit scroungers, not wealthy tax dodgers, PPE-fund grabbers and rent-raising landlords emboldened by their mates in parliament –who are doing the country down.

The PM suggested that around half the people who are judged to be unable to work are signed off with depression or anxiety – with a heavy implication, even in these supposedly enlightened days on mental health issues – that many should be working.

Except that his comments were premised on a misunderstanding of the figures. Just over half of people judged medically unable to work have depression or anxiety – around 1.35 million. However, more than 1m of them had depression or anxiety as a secondary condition, rather than the reason for which they were signed off.

Being ill for a long time can itself be a driver of both. Either No. 10 is so incompetent that it failed to realise what the numbers meant, or else it is so callous that it didn’t care.

All of this failure makes Sunak’s decision to press through legislation to stop smoking look curious. It is not a traditionally Tory policy: both his immediate predecessors have publicly scorned it. Several cabinet ministers, including ambitious Kemi Badenoch, are on the record as opposing it.

Sunak is hardly a soft Tory by background – his interventions during the pandemic were against his natural small-state political instincts, and reporting has suggested he was a consistent voice in opening up faster, against public health advice.

Why, then, did he spend so much of his dwindling political capital on pushing through the legislation? So weak was his position on the issue that he allowed the measure to be a free vote, meaning serving ministers could vote against it without retaliation.

In the end, Sunak managed to get the support of just over half of his own MPs – more than 100 abstained and over 50 actively voted against the government. Labour and the opposition parties, by contrast, almost universally supported the legislation.

It is obvious that passing the anti-smoking legislation did absolutely nothing to help Sunak’s precarious position, and might even have made it worse than it was before. That in itself is enough to answer the question as to why he pushed it through: it is the strongest evidence yet that Rishi Sunak has given up.

One way or another, Sunak won’t be prime minister in a year’s time. He will either be evicted by his own MPs in the next few weeks, or else jettisoned by the electorate in the next few months. He will doubtless quit parliament soon afterwards.

Sunak’s political career is at its end and he knows it, for all that he will go through the motions of chasing popularity with silly speeches about “sicknote culture”.

The smoking legislation is there to be his legacy: never mind whether it’s actually practical, workable or in line with his ideology – by passing that bill, he can say he is the prime minister who ended smoking in the UK, and by doing that he surely hopes that he can avoid his premiership being an embarrassing footnote like that of Truss.

Some Tory MPs must surely have realised this too. Rishi Sunak is going through the motions, but he’s a man who has already checked out.