Last week, in a Berlin suburb, I watched a young American computer programmer attempt, in German worse than mine, to get the TV turned on in a smoky working-class pub, so he could watch Real Madrid. He failed, but without acrimony.

Later, around the corner, I ate organic Wienerschnitzel in a restaurant filled with the same kind of person: young, tecchie, cosmopolitan and transatlantic – some wearing hoodies branded by the mobile comms company they worked for.

At the coffee shop, next morning, they were there again – one couple actually snogged over their cardamom swirls, while others, wearing oversize earphones, quietly typed computer code into their laptops.

This, in case it’s not obvious, is what innovation looks like. In our century, it is done by young people who will move to any city so long as the pay is good, the vibe is great, the food organic, the nightlife exciting and decent housing actually available.

Last month, as he does with monotonous regularity, Jeremy Hunt pledged to turn Britain into the next Silicon Valley. Just as Dominic Cummings pledged to build a trillion-dollar UK tech company, and Boris Johnson promised to make us a “space superpower”.

To understand why all such promises will remain hollow, you just have to turn on the TV and listen to what else Tory politicians are saying. They’re anti-woke. They despise the left wing “blob” of human rights lawyers and civil servants. They want to represent David Goodhart’s “somewheres”, not the rootless, cosmopolitan “anywheres”, who they denigrate on principle.

Well, the anywheres can take the hint. And the clue is in the name: if talented enough, they will actually go “anywhere” to avoid the kind of government-sanctioned hate speech the Tories are spouting, and the kind of society it produces. They know, as the saying goes, that “a fascist with a baseball bat doesn’t know you’ve got a PhD”.

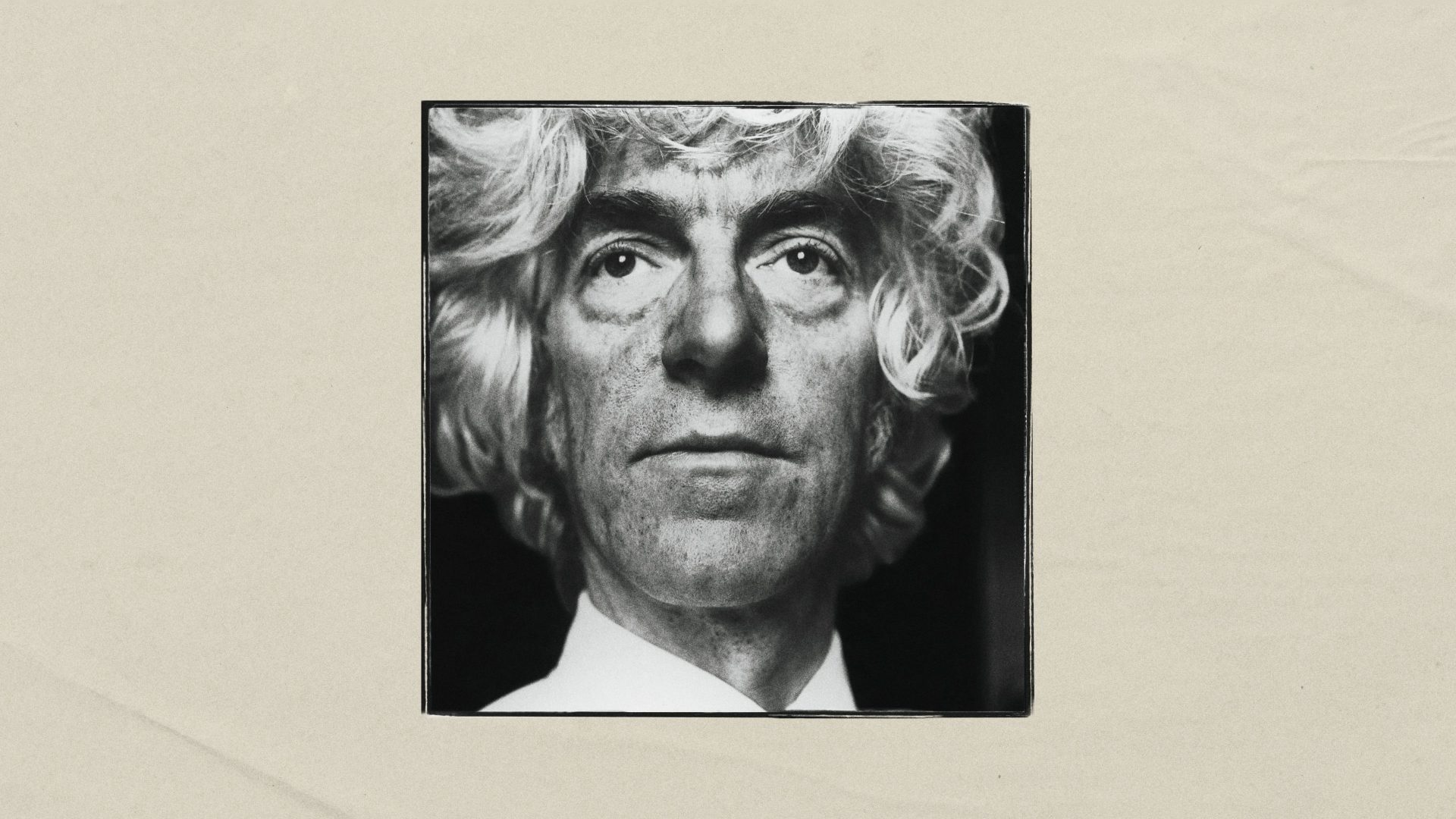

They can also smell when the ingredients for success are there – and unfortunately, Brexit is not one of them. That’s why Hermann Hauser, one of Britain’s greatest tech pioneers, recently burst out laughing when Newsnight asked what the chances were of the UK emulating California. “Zero,” he replied.

In a world wracked by geopolitical tension and systemic competition, “emulating Silicon Valley” no longer means simply attracting venture capital into startup companies. It means accumulating a tech ecosystem that ranges from pure science through semiconductor design, and bespoke artificial intelligence models, to the engineers and systems architects who can apply innovations rapidly to real-world industrial production.

The reason the UK is lagging in all this is not just that we de-industrialised under Margaret Thatcher, and that our education system produces too few teenagers with maths and science skills. It is the absence of scale.

The only scale at which the tech giants of the 21st century will operate is continental. As Hauser explained to Newsnight, only the US, China and Europe have the scale to achieve technological sovereignty. Next door to us, the European Union has just agreed to pour €6.2bn of subsidies into semiconductor design and manufacturing, alongside €2.6bn already committed – with the aim of doubling its share of global semiconductor production.

That’s what those young people in Berlin know they are part of, and our young innovators are barred from.

We know the other classic ingredients of Silicon Valley: world-class universities, capital prepared to take long-term risks, and a state prepared to underwrite the risks and pick winners, using its military-industrial complex to stimulate tech innovation. It’s not that the UK has none of the above: it’s just that no government has ever made them gel together into a self-reproducing ecosystem.

In the next few weeks, more than 900,000 young people will graduate from British universities. Among them will be just 60,000 engineers, 50,000 computer scientists and 16,000 mathematicians.

It’s not that London is an unattractive place for the highest fliers among them; it is that the most attractive jobs will be in financial analysis or business consulting – and even then, their chances of owning a home anytime soon will be limited.

So Berlin, with its cheap cosmopolitan nightlife, Paris with the biggest tech sector in Europe, and of course, the actual Silicon Valley – and its offshoots now in Texas, Toronto and New York – are realistic career choices for British high-fliers, just as Australia has become a mecca for UK qualified nurses and medics.

So Hauser is right. Brexit has seriously damaged Britain’s ability to be part of a tech innovation story with a continental scale. Worse, the atmosphere it has created – xenophobia and the celebration of ignorance – leaves many talented young people nonplussed.

Putting this right, on top of the huge distortions created by the loss of industrial capacity and our obsession with speculative finance, will take serious work. A state-led industrial strategy; a skills strategy that relies on more than hit and hope.

And, as Rishi Sunak says, we need more engineering, maths and computing graduates and more of them need to be women.

But ultimately it’s about a vibe. Machines don’t innovate. Nor does money.

Only people do – and to do it here, they have to believe this is a country with a future, not just a past.