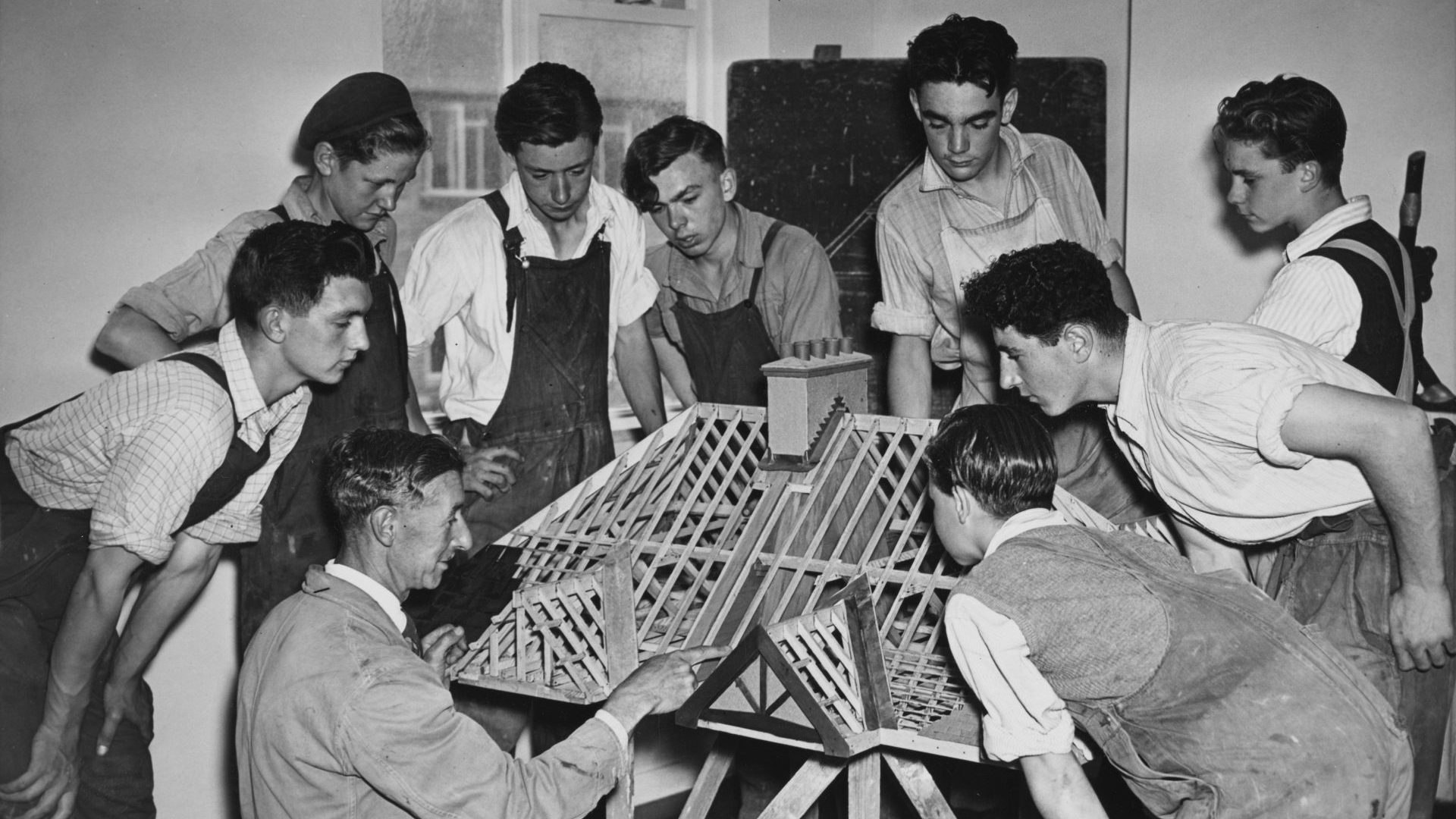

It can be a strange experience to hear what Westminster was like in decades past. In a recent conversation, it came up that someone I knew had worked for a senior Labour MP “many years ago” and had mixed recollections of the era.

Parliament would be soaked with booze daily, he recalled, as the Commons still had all-night sittings, and bars in the Palace of Westminster – handily exempt from licensing laws – would stay open to keep members well lubricated.

Their poor staff would have to stay at work for as long as their MP was present – but they would be far less welcome in the bars, even if it was only to buy matches. Oddly, my interlocutor recalled Labour MPs being worse tyrants than their Conservative counterparts.

The era of “noblesse oblige” still, he argued, existed as the abiding spirit among Conservative MPs – while bullied Labour researchers would eventually be advised by the whisper network to mention seeing the Constituency Labour Party chair in a week or two. Dinners and nicer treatment – for a good report – would soon follow.

How times change – and how they don’t. Years later, while the Commons no longer sits all night, its bars still prove controversial with the public and are tricky places to navigate for staff.

Instead of having to rely on the charity of a constituency party chair, bullied or sexually harassed researchers can now turn to a years-long, drawn-out and gruelling complaints procedure against MPs. And any sense of obligation – noble or otherwise – felt by Conservative members of parliament certainly feels like a relic of the distant past.

It is the fate of those working for MPs who rise to ministerial ranks that has drawn the most recent headlines, though – Dominic Raab is facing an independent investigation into three separate allegations of bullying against civil servants, career officials who didn’t ever sign up for the full Westminster psychodrama.

But his is hardly an isolated case, and those lodging complaints against him have little reason to be reassured by recent history. Most notably, Priti Patel was found by multiple official investigations to have bullied her civil servants – and continued on as a minister regardless, despite public money having been used to pay settlements against civil servants she abused.

But there is a wider culture of ministers railing against and being dismissive of their officials – Jacob Rees-Mogg notoriously wandered around government departments, leaving passive-aggressive notes castigating officials for not being at their desk.

He did this while he was the minister responsible for government efficiency, apparently unaware that government efficiency measures had, in fact, sold off large amounts of government office space – meaning that even if every single civil servant either wanted or needed to work from the office, they would not be able to.

We’ll examine the roots of ministers’ newly dysfunctional and abusive relationship with their officials, but we should first note why it is particularly awful. It should be a statement of the obvious to say that everyone should be able to go to work without worrying about being abused, and that public servants – who have endured years of pay restraint and cuts – should not face being denigrated as well as financially mauled.

However, things go further in that ministers are supposed to be representatives of their departments and are how departments are held accountable to parliament. Because of this unique role, there is a longstanding convention that civil servants shouldn’t take public stances and absolutely must not criticise their ministers.

Given the one-sided nature of that compact – ministers can speak but officials cannot – it has been a long-standing convention for ministers not to criticise their departments beyond broad generalities (typically when they’re new in post). To routinely denigrate people who are not allowed to answer you back is a textbook example of bullying behaviour.

Why are ministers facing this new wave of bullying allegations – and why are they behaving in such roughshod ways with officials even when it falls short of those thresholds? Part of the answer, of course, lies in the fact that ministers are products of the UK’s political system.

They were all MPs before they were ministers, and got used to parliament’s largely unreformed culture with researchers and other junior staffers.

A large fraction of ministers were once those researchers or advisers themselves. Ministers’ ideas of what a normal workplace looks like will necessarily be dramatically different from most people who have never interacted with parliament – and most civil servants have little need ever to set foot in the place.

Westminster’s decades-old cultural problems are exacerbated by newer ones – not least Brexit and the subsequent clash between ideology and reality that it has fuelled. The civil service is pretty much designed to be the bore at the party, reminding you that an extra drink will mean a hangover, that you’ve got an early start tomorrow, and can you really afford to take an Uber rather than three buses home?

The civil service’s institutional role to deal with the world as it is, and to deal with the consequences of ministerial decisions, has naturally put it on the wrong side of that subset of Brexiteers who believed – and often still believe – that what has stopped Brexit being a rocking success is internal sabotage, insufficient belief in Britain, or some failure to negotiate a settlement entirely on our own terms with the rest of the world.

By getting lumped in with their political opponents, the civil service – largely blamelessly – can come to be seen as the enemy within by any politician of those factions. Thanks to Boris Johnson’s 2019 purge of the Conservative parliamentary ranks, that is now the overwhelming majority of MPs – and so a sizeable majority of ministers.

Add into that the difficulties of entering a department when you’re 12 years into your party being in power, there being essentially no cash to spend, the hideous waste you’d expected to be able to cut being largely non-existent, and morale being through the floor, and being a minister isn’t all that much fun these days. And what does a petulant or irritable character do when things aren’t going their way? Lash out, of course!

It should be remembered that several key ministers had careers outside of politics, of course – but the current and recently departed tranche of cabinet ministers have mixed records (at best) there, too.

Grant Shapps might be relatively well regarded as a minister – the key word here is “relatively” – but his previous, controversial online marketing ventures were notoriously not pleasant places to work. Nadhim Zahawi, another minister with a business background, can hardly claim that his previous employment was unrelated to politics – given that he was at the helm of YouGov for years before entering parliament.

Rees-Mogg’s background is in emerging market hedge funds, while others got into politics not even through the Conservative Party but James Goldsmith’s somewhat erratic (and long-defunct) Referendum Party, which once employed Patel.

Alarmingly few of the people running the country’s public services seem to ever have worked at their coalfaces: where are the former doctors, teachers, nurses, or even public administrators? How can you run organisations with a service ethos if you’ve never seen what it is to work in that firsthand? If your instinct is that the private sector is where the action is at, why commit yourself to elected public service in the first place?

The consequences of Westminster’s strange culture and its failure to reform go beyond the confines of SW1. They are, of course, most acutely felt by the officials and researchers who find themselves having to bend to the whim of their political “masters” just as much now as they did decades before.

But these things ripple across society – a dysfunctional work environment will produce dysfunctional work. Staff who are afraid of their boss – or even just unwilling to present them with bad news – will supply worse advice than those who aren’t. What starts as a small gap in information or decision-making gets larger and larger with time.

Once we are this far into a government’s lifespan, the consequences of bad ministerial culture are everywhere. Much of the UK’s malaise is the result of austerity, underfunding of public services, and chaos around Brexit. But some of it is down to simple mismanagement, and that is because of a toxic culture in British politics.

None of these problems are new, and few of them are unique to the Conservative Party – but recognising them now could be the root of fixing them. If Labour wins the next election and comes into government, the time to put in genuinely robust and independent accountability for ministers and MPs alike is right away – before Labour has its own governmental scandals and tiffs, and before ministers start musing on whether they really want to make life more difficult for themselves.

Tackling the culture of bullying and denigration of the civil service isn’t just an issue of workplace health or even of “vibes” – it’s part of a mission to govern the country better. It’s good policy and, if played right, good politics, too.

Labour should set out a charter with clear and sweeping reform, and dare the Conservatives to oppose it. If nothing else, it might give new ministers and officials a better first day at work together.