The language which was spoken in what is now England before the Norman conquest is normally known today as Old English, but it has also been called Anglo-Saxon.

This is because the two major groups of West Germanic speakers who crossed the North Sea and settled in Britain as the Romans were departing were the Angles and the Saxons. The Angles originally came from southern Jutland and northern Schleswig-Holstein. The Saxons came from further west, along the North Sea coastal areas of northern Germany in the Elbe-Weser region.

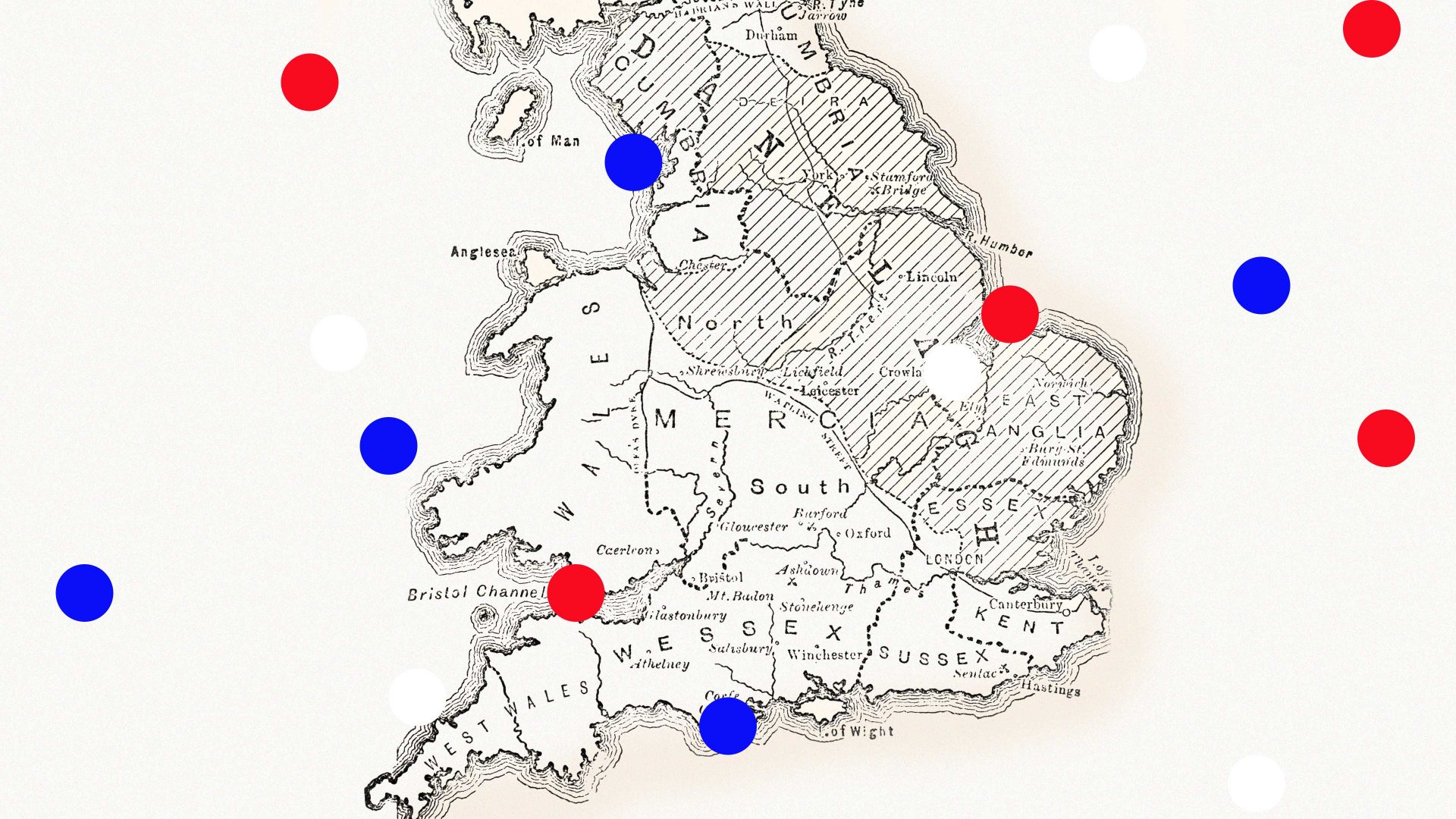

The major entry points into Britain for these people were the great estuaries of the English east coast: the Humber, the Wash, the Great Estuary (the Gariensis Ostium of the Bure, Yare and Waveney by Yarmouth), the estuary created by the Stour and the Orwell at Harwich, and the Thames Estuary. It was the Saxons who eventually gave their name to the areas of southern England known as Wessex, Sussex, Middlesex and Essex, the names referring respectively to the West, South, Middle and East Saxons.

In these Saxon-dominated areas of England, we find a few placenames which indicate rather clearly that most people in Wessex were not Angles, such as the settlement of Englefield, now in Berkshire, which meant the “field of the Angles”, and Englebourne, “stream of the Angles”, in Devon.

Most of non-Saxon England and south-eastern Scotland came to be dominated by the Angles. In these Anglian zones, there are still to this day village names such as Saxham “homestead of the Saxons” near Bury St Edmunds, and Saxton “farmstead of the Saxons” in North Yorkshire. These villages were obviously so called because there was something unusual about being a Saxon in Suffolk and Yorkshire. We do have written records of that earliest form of our language, and these records show that – just as today – (Old) English had a number of different regional dialects.

In fact, it had four main dialects which were to an extent associated with four particular Anglian and Saxon kingdoms: Mercia, focused on Tamworth, now in Staffordshire; Northumbria, with its capital in York; Kent, based around Canterbury; and Wessex, whose capital was in Winchester. Mercia and Northumbria were basically Anglian in origin, and Wessex was Saxon.

It is interesting that sometimes these ancient dialectal differences can be seen to have survived to an extent into Modern English. Today, for instance, The Weald is the name given to the areas of the Sussex, Kent and Surrey countryside which lie between the North Downs and the South Downs, and which are, or were formerly, wooded. Weald is etymologically related to the German word Wald “wood, forest”. The same word occurs in the name of the Essex village of North Weald, where it clearly refers to Epping Forest. There is also an Oxfordshire village with the same name.

But if we look beyond the south-east of England, we then notice that names with weald become less common and we find instead names with wold, such as the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Wolds, Ashton Wold in Northamptonshire, and Southwold in Suffolk. It is a bit of a simplification to say that wold was in origin an Anglian dialect form and weald was Saxon, but that is not too far from the truth.

DOWNS

The word downs, which paradoxically means “uplands” – particularly uncultivated land with rolling hills – is likely to be of Celtic origin. The Roman place names for the ancient British sites Camulodunum (Colchester), Branodunum (Brancaster, Norfolk), and Sorviodunum (Salisbury, Wiltshire) all contain the probably Celtic element dunum signifying “hill fort”.