Britain’s economic policy regime is stuck. The Bank of England’s 2% inflation target mandates high interest rates. This cuts into household spending to trigger an inevitable recession. The fiscal targets adopted both by the government and Labour are a recipe for austerity, preventing vital investment in the jobs, industries and public services of the future.

Our basic problem is stagnation, but our economic doctrine only leads to more of it. And it’s not just a question of bad policy choices. With UK government debt breaching 100% of GDP, and the yield on that debt just below the 4.6% peak it reached during the Liz Truss fiasco, it’s just a fundamentally bad situation.

I wince every time Labour torches one of its spending commitments, but I understand why they are doing it. The Thames Water crisis shows how low growth, high interest rates and long-term financial predation can suddenly eviscerate a company. But this can happen to the economy, too.

To get out of this, we’re going to need regime change: not of the kind that sees tanks on the streets, though it might feel as shocking when it happens. We need a regime change of economic policy and institutions.

None of the institutions – the Treasury, the Bank of England, the Office for Budget Responsibility, and the bevy of economics editors who’ve sat like nodding donkeys as the Tories drove us into this swamp – can articulate an answer.

The Treasury does not believe in long-term fiscal multipliers, the idea that a pound invested now will yield two pounds’ worth of growth over time. So it cannot propose an escape plan in which the government borrows to invest, the long-term output potential of the economy grows and the debt to GDP ratio shrinks.

The BoE’s 2% inflation target translates into massive economic pain for mortgage holders. The OBR underestimates the damage inflicted by this toxic mixture of monetary and fiscal austerity, and goes on rubber-stamping over-optimistic predictions.

And no political party dare yet explain what’s got us here: decades of deindustrialisation, financial speculation and asset stripping, made worse by the catastrophe of hard Brexit. It has tanked business investment, damaged trade and weakened the pound.

As for growth through innovation and productivity, you can forget it. Our hollowed-out and heavily indebted private sector shows no signs of making the necessary investments. Only the state could do it.

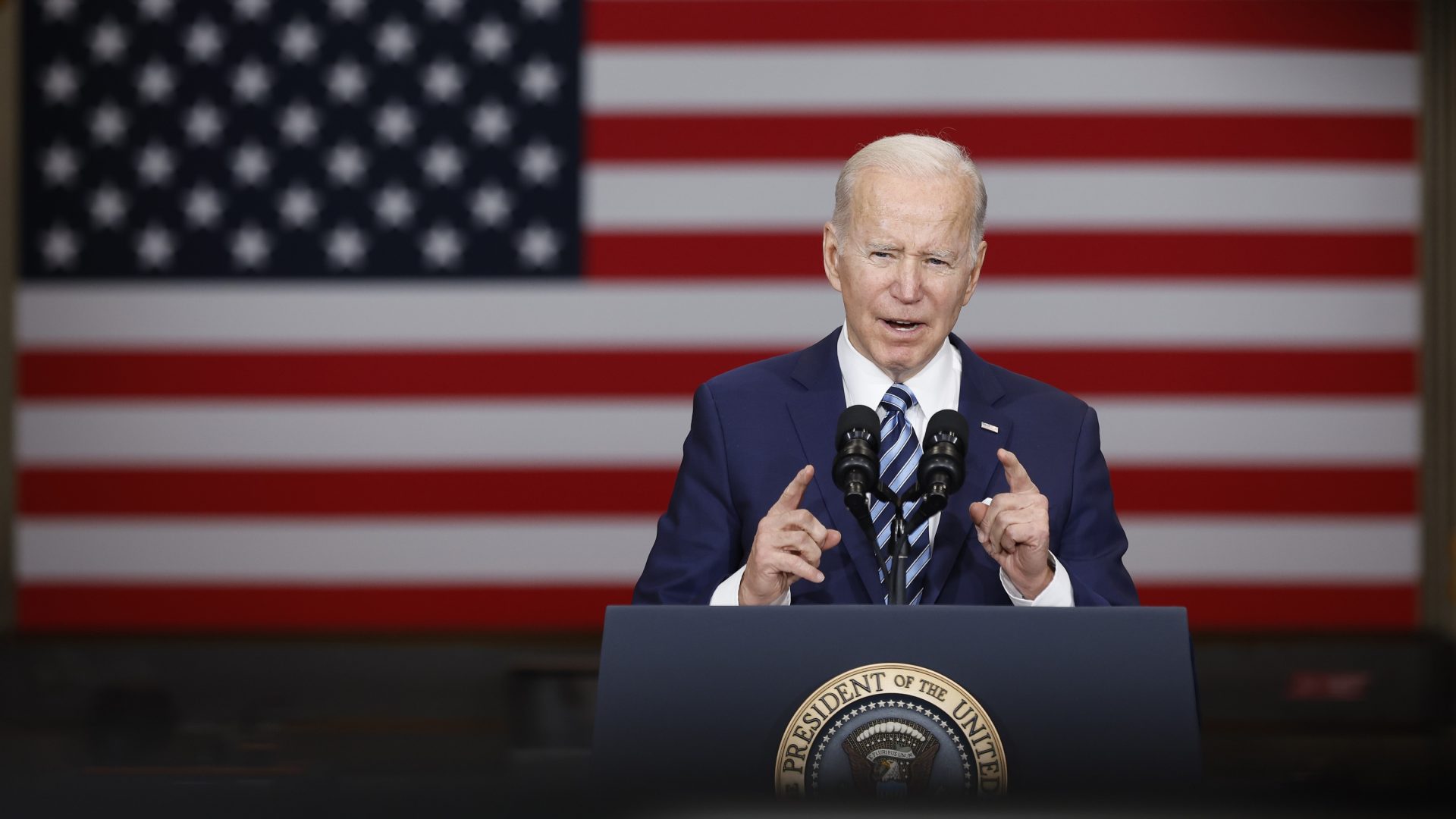

But there’s the problem. Last week President Biden made a speech outlining the principal tenets of “Bidenomics”: state-directed investment in green energy and the technologies of the future, massive infrastructure investment and the most pro-trade union administration in US history – all done not just to boost national security but to end the hollowing out of communities by offshoring and the loss of skills.

Rishi Sunak could not make that speech. First, because he doesn’t believe in it. He believes in trickle-down economics, as does everyone around him.

Second, because he cannot deliver any of it: he’s at war with public-sector workers. He’s burdened with a Treasury orthodoxy that will not sanction investment-led growth. And he’s hamstrung by his own inflation target.

Worse, even if he did suddenly convert to the kind of British Bidenomics that Rachel Reeves has been advocating, he could not take the parliamentary Tory party with him: even on the low-hanging fruit of house building and renewable energy, they are determined to conduct a guerrilla war against affordable homes, electricity pylons and solar farms.

Bidenomics is working. We are two years into it; it is sucking global investment into America while Sunak stages woo-woo conferences about AI systems that will be built elsewhere.

There are six things the government could do, but won’t. I’m not asking Labour to commit to them now, but to implement them once there is a mandate.

First, raise the 2% inflation target to 4% until the global inflationary pressures – post-Covid disruptions, deglobalisation and Russia’s energy war – subside.

Second, commit to restoring public-sector pay. As Gianni Agnelli, the founder of Fiat, said during a 1920 standoff with his workforce: “you cannot make anything with 25,000 enemies”. How much truer is this for the NHS, university, rail, social care and local council workforces.

Third, accept that tough fiscal rules are not working. We need credible fiscal rules, based on the belief that borrowing to invest should, over the medium term, have a positive impact on Britain’s growth potential.

Fourth, use temporary price caps to suppress profiteering and defend real wages. The experience of Spain, where inflation is now below 2% because it implemented energy and transport price caps early, and cut indirect taxes, shows what could be achieved.

Fifth, announce a policy of investment-led growth. “We will borrow to invest and the subsequent growth will reduce the debt burden and raise private sector wages”: that’s all Reeves needs to say.

Sixth, announce a policy of voluntary alignment and re-engagement with the European single market, slashing the post-Brexit obstacles to recruitment and trade. Sign up to as many as possible of Europe’s own Bidenomics projects and signal to the world that our economic future is aligned with the EU.

I don’t need a list of spending commitments from Labour. I need a signal that it understands: it will have one chance to enact regime change, before the economic swamp we’re in engulfs the incoming government.