Immigration into Britain surged in the year to June 2021. More than a million new people arrived as long-term migrants, while half a million left – we think. Because one of the strangest things about Britain, a country whose media is obsessed with migrants, is that it has no way of counting them.

The latest Office for National Statistics figures, showing net immigration at a record 504,000, are “experimental and provisional, based on administrative and survey data”. Even then, they exclude the estimated 34,000 people who arrived in the relevant period in cross-Channel dinghies.

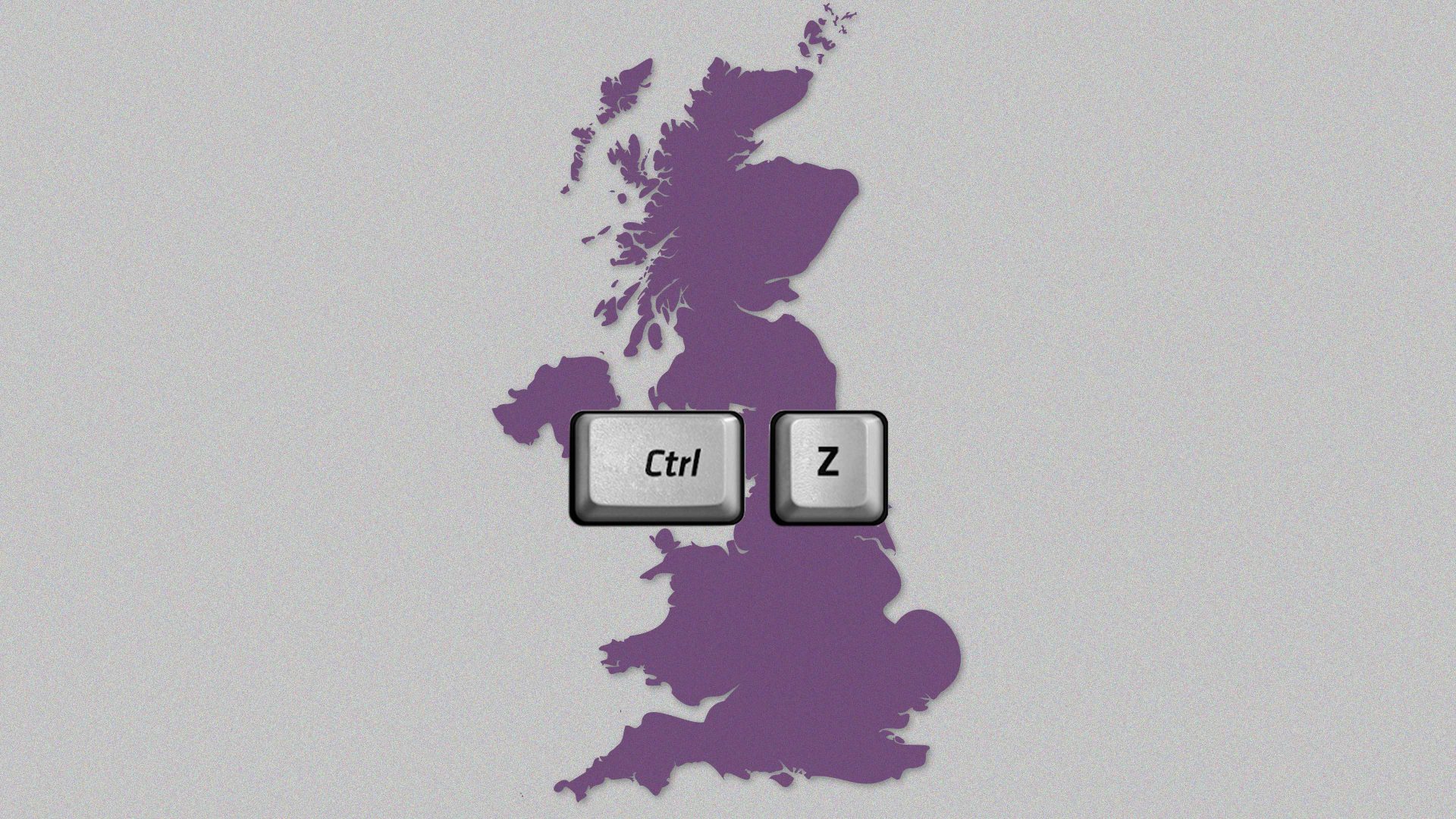

Given that Brexit was achieved by politicians promising to cut net migration to “tens of thousands”, you might expect the sudden rise to half a million to be causing riots in the streets.

But it isn’t. Some 89,000 Ukrainians have been absorbed into the fabric of British life – albeit with hardship for them, some administrative chaos and predatory behaviour by landlords. Another 76,000 arrived from Hong Kong, as British Nationals Overseas. Meanwhile, the majority of non-EU arrivals were students, paying up to £32,000 a year.

Europeans, whose presence in the UK labour market so enraged people in the run-up to Brexit, are leaving faster than they are arriving. Rising living standards and the falling pound have made it more attractive to stay in countries like Poland and Slovenia.

In short, the post-Covid recovery in international migration, combined with state failure, war and repression across the world, created an unprecedented increase. But it has proved manageable and – according to the latest methodology of the Office for Budget Responsibility – good for the economy.

As a result, there has been less angst in the tabloids over the arrival of a million people legally than over the 34,000 arriving on boats – most of whom, of course, are subsequently granted asylum.

There is, in short, a massive cognitive dissonance going on. Brexit was supposed to decrease migration and, by some simple analogue, drive up the wages of the least-skilled Brits. But the opposite has happened.

Real wages are falling so fast that, by 2025, the average family will be back to where they were in 2014, and won’t recover their pre-pandemic living standards until the end of this decade. And that’s got nothing to do with migration, and everything to do with the war-inflicted cost-of-living squeeze.

If anyone doubts that we need to learn to live with high migration, this week’s figures should be the clincher. The question is how.

Both main parties are now committed to a “points-based” immigration system, with Keir Starmer abandoning his former commitment to restore freedom of movement with the EU and any kind of common trade area giving migration rights to those within it.

I think he and we will come to regret that. Freedom of movement certainly created problems of equity. Small-town Britain was faced with sudden strains on its public services, from a new kind of immigrant who in some cases made no commitment to citizenship or cultural integration, and who could not vote in general elections.

But there were solutions: more housebuilding, union rights, more money for public services, equal political rights. I will never forget the day I put these arguments to a London taxi driver in 2016. “Mate,” he said, “I see all that, but it would be a lot easier just to kick them out.”

Well, 275,000 EU nationals kicked themselves out in the year to June 2022, which is 51,000 more than arrived. And yes, that means more than 224,000 people did arrive here from Europe on visas, even without freedom of movement – double the target figure Theresa May promised that taxi driver.

So immigration is a fact of the 21st century – particularly for a country like ours that has chosen to de-industrialise its economy and de-skill its workforce.

There are engineering factories in England that would double their workforce – earning very decent money – if they could find the people. There’s an A&E department in Wales that will soon close because the hospital cannot attract enough specialist doctors. There are 165,000 missing workers in the care-home sector. As for finding a skilled welder, good luck.

Starmer is right that, in the long-term, part of the solution is to train such people ourselves or to automate faster. But since you cannot automate social care, for example, there are limits to the latter. And without migration, Britain is an ageing society – so will never have enough people to staff its hospital wards and care homes without some major demographic change.

In the short term, we have to learn not just to live with, but also to appreciate inward migration. This would become a lot easier if the UK had a unified national story to tell. But its actual national story, thanks to two decades of flirtation with right wing populism – is division and self-hate.

It’s not just the Tory tabloids who hate the real Britain; it’s the Question Time audience selected by the BBC. Even Rishi Sunak, proud son of a migrant family, is frantically looking for ways to stop students coming from the Indian sub-continent to boost the figures.

The solution is not just to make the points system fair (above all to Europeans whom it needs to attract in larger numbers); or to provide safe legal routes for asylum seekers, and to let them work. It is to accept the multi-ethnicity of the British people and to give everyone who lives and works here, after, say, 12 months, all the rights of citizenship – even if they be temporary.

And then to fight for this vision politically. As a doorstep campaigner, I am all too aware of how hard that will be. But I hope the scale of Tory failure, by their own metrics, will start to convince Conservative voters that the low-migration dream they were sold via Brexit was a chimera.