On the third floor of an apartment block, a panicked man in pyjamas stretches out of his metal balcony, reaching out to an ambitious child now clinging on to a washing line suspended high above the road below.

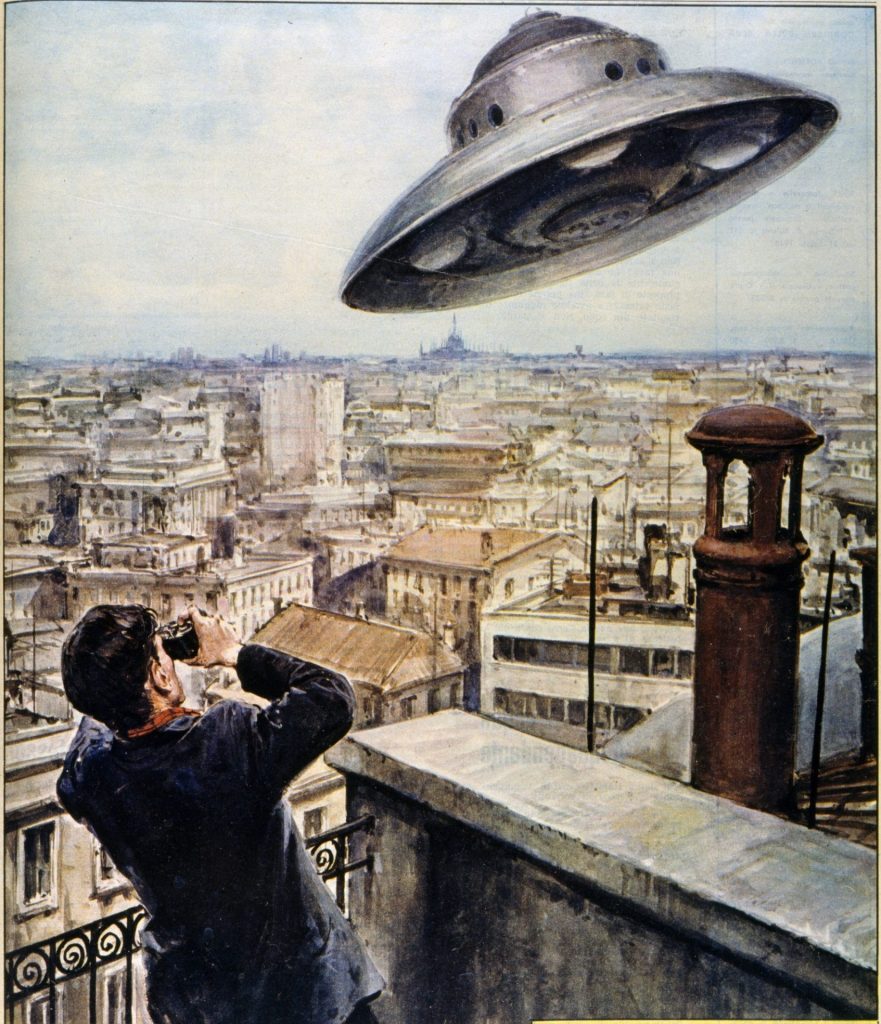

On a rooftop above a European city where sandstone buildings stretch towards the horizon, a young man with a camera reels backwards as a UFO tilts before him.

On horseback in velvet and brocade, his men in cloth robes by his side, Ethiopian royal Ras Makonnen fires his pistol at Italian invaders during the battle of Adwa.

On a very 1950s high street, commuters of the future tip their hats to one another as they pass, each standing in their own glass-encased domed vehicle.

And on a rowing boat that a storm has tipped towards the water, a teacher and a nun struggle to keep hold of a terrified party of schoolgirls as their classmates tumble into the roiling sea.

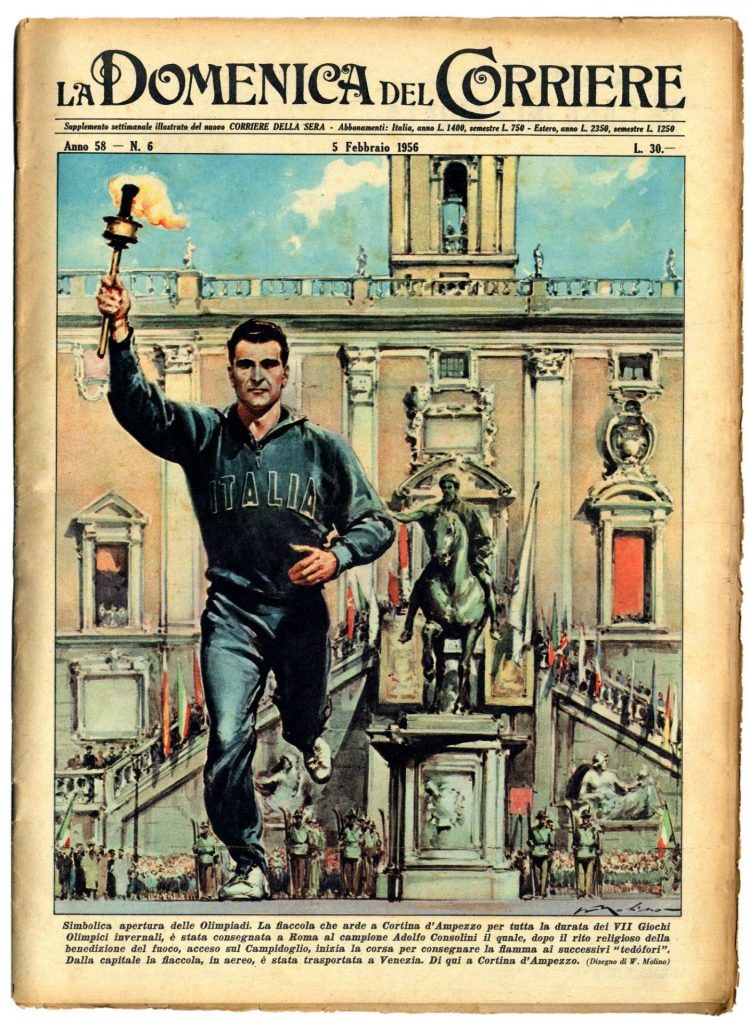

Operating in an age when the art of photography was making leaps and bounds, the Italian illustrator Walter Molino captured the moments the camera could not, for reasons of timing, technology or taste.

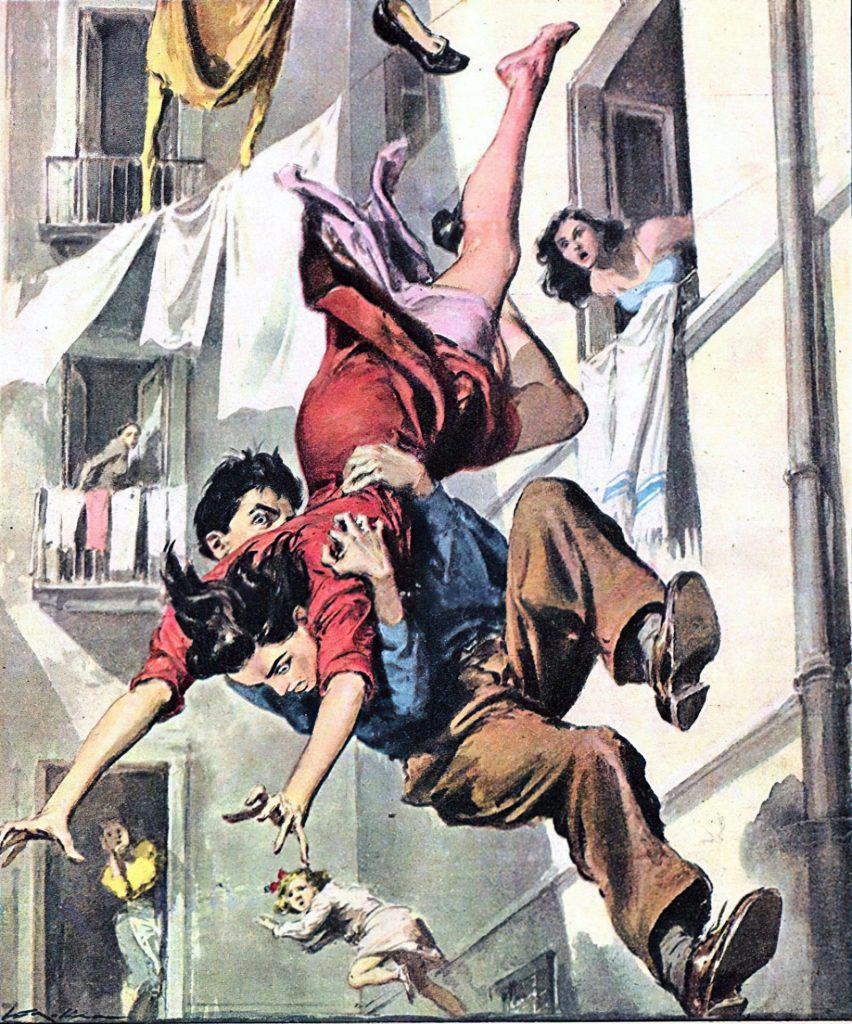

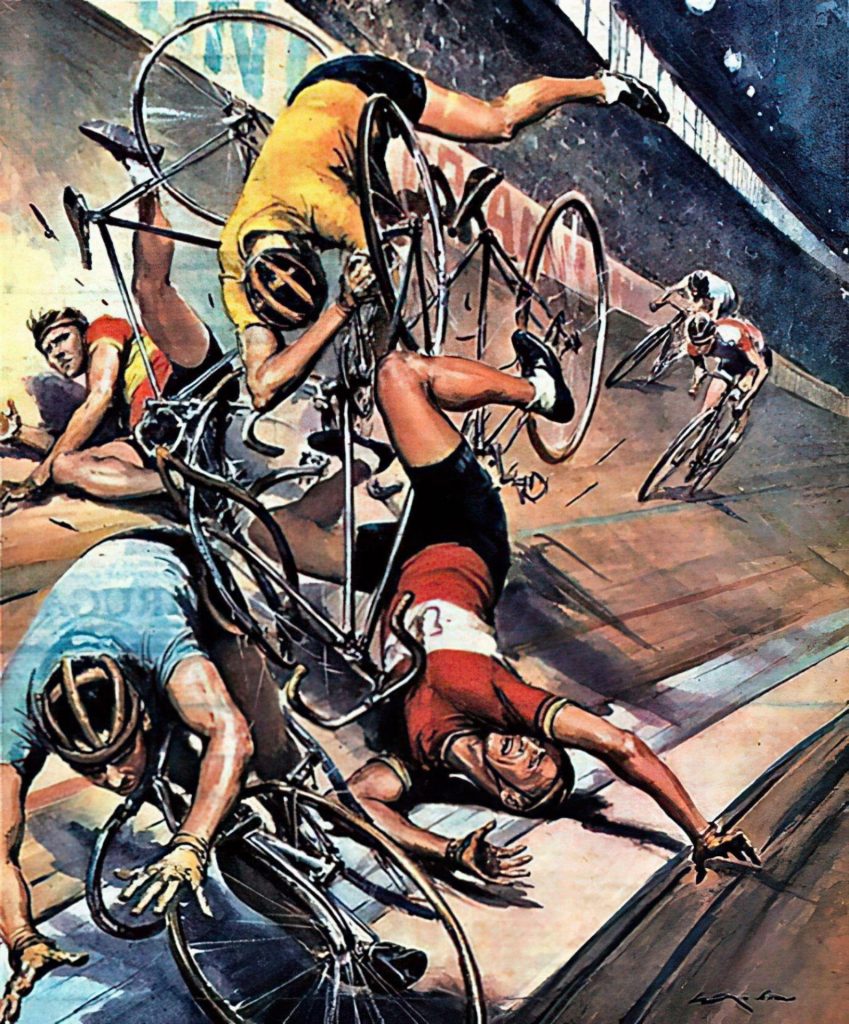

A comic strip artist who found his metier producing pulpy but highly dramatic and deeply compelling cover paintings for the Italian news weekly La Domenica del Corriere, his characters are caught leaping, bounding, falling, crashing, drowning, dying in a series of painstakingly created snapshots by a sensational talent with an appetite for the sensational.

Few before him had been able to realise motion in so natural and thrilling a fashion. Molino recognised this, and he pushed it to extremes.

His situations are therefore often absurdly dramatic (a mother clutching her terrified child in a tight corridor between two passing trains; a furious woman thrashing her suitor with the roses he’s presumably just handed her), and sometimes they are just absurd (a bull’s head crashing through a train carriage window; a passing eagle dropping a lamb into the middle of a picnic; a family on a boating lake terrorised and capsized by feral swans).

Sometimes they are lurid, morbid; none more so than the image of a crashed car pinning five short-trousered schoolboys to a fence. “Pesso Torino falcia cinque bambini” reads the caption – five children mowed down near Turin. In another gruesome drawing, a short-trousered schoolboy is tossed through the air as a red race car smashes into a watching crowd.

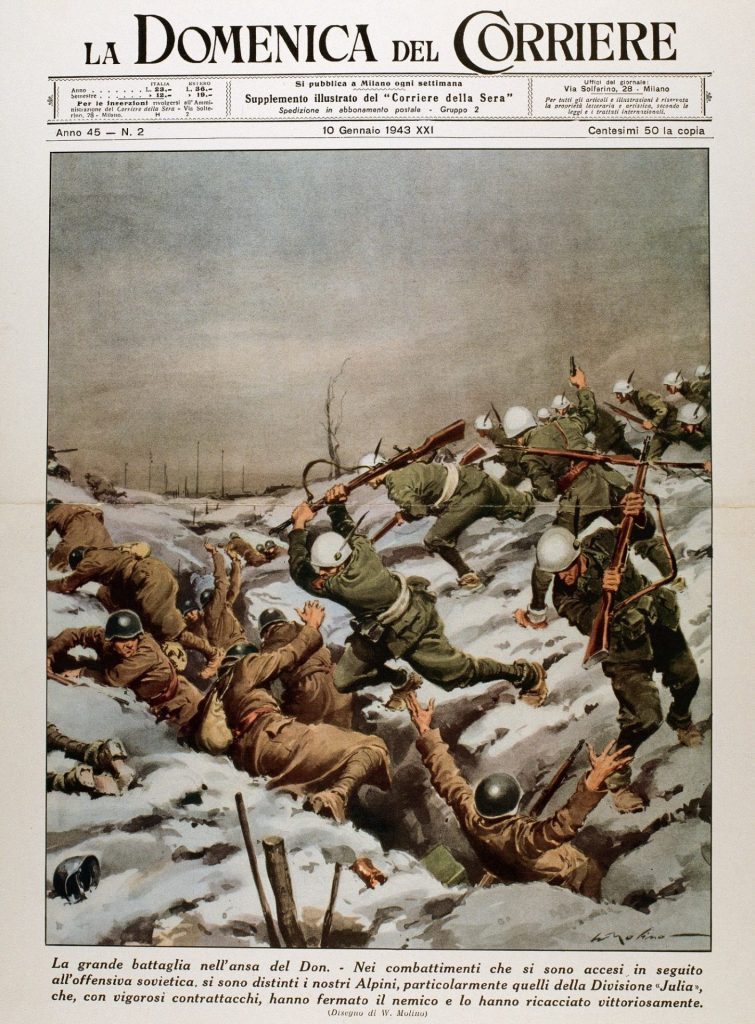

And since Molino joined La Domenica during the second world war – his student work having already been spotted by Benito Mussolini, securing him commissions from Fascist Party newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia – his drawings are often highly questionable, with American soldiers strafed by a “great German offensive” or bayoneted by the Japanese in jungle combat. It reinforces the idea of Molino as a dark counterpart of Norman Rockwell, whose idealised portraits of small-town America first appeared on covers of US weekly magazine the Saturday Evening Post in 1916, when the Italian was just a year old.

Both men share a mastery of anatomy and of light. Both can be called naturalists although their work goes beyond the natural, both can be accused of kitsch. But while Rockwell embodies sentimental warmth and dreamlike optimism, Molino’s drawings for La Domenica del Corriere are of panic in suburbia, things going wrong, the stuff of nightmares.

Rockwell’s boys sit at soda counters with their fathers or trot obediently to school behind their sisters; Molino’s fall from balconies or are hit by cars.

Rockwell would almost certainly have preferred the work Molino created for Grand Hotel, another Italian weekly, after the war. Inside, he produced beautiful ink wash cineromanzi – comic-romantic strips featuring characters who look very like the Italian film stars then lifting the national mood.

His covers stray into Rockwell territory; one masterful illustration shows a very glamorous and very bored woman filing her nails in a football stadium as the men around gurn and gesture in frustration at the action on the pitch. It would make a memorable sequence in a Marilyn Monroe movie; it’s all there in one wonderful frame.

It’s the La Domenica del Corriere covers that grab you though. They seem to encapsulate Italy’s turmoil in the middle of the 20th century just as Rockwell spoke to a country emerging from depression into comfort. The American brings harmony, faith, hope; the Italian discord, doubt, despair. In Walter Molino, a time of chaos and confusion had found its maestro.