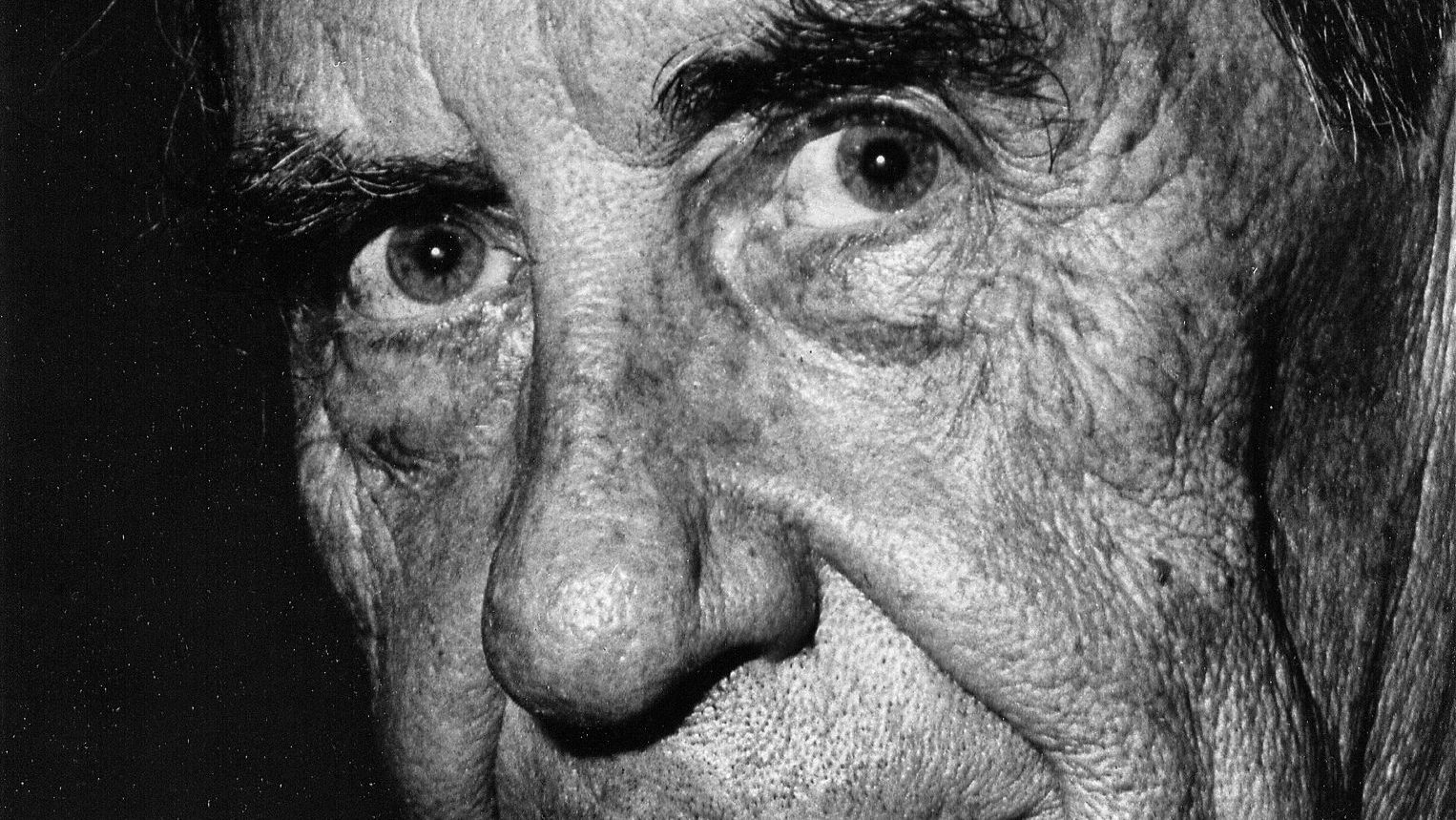

Posterity has not been particularly kind to Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus movement and arguably the most important figure in modern architecture.

Architectural historian Joseph Rykwert described Gropius as a man who “seemed to have fewer redeeming features than many of his kind” and whose “pinched humourless egotism was unrelieved by sparkle”. In his 1981 book From Bauhaus to Our House, Tom Wolfe lampooned Gropius for designing buildings to look like “an insecticide refinery”.

Even fiction provided no refuge. Evelyn Waugh’s novel Decline and Fall features professor Otto Silenus, a German architect riddled with stereotypical Teutonic humourlessness who is clearly inspired by Gropius, drafted in by Mrs Beste-Chetwynde to design something “clean and square” after seeing his “rejected design for a chewing-gum factory which had been reproduced in a progressive Hungarian quarterly”.

“The problem of architecture as I see it,” muses Silenus, “is the problem of all art – the elimination of the human element from the consideration of form. The only perfect building must be the factory, because that is built to house machines, not men.”

This portrayal could not have been further from a man whose work was shaped by a philosophical vision infused with nuance, warmth and joy. Gropius envisioned homes and workplaces filled with light that were a springboard for lives of happiness and fulfilment.

Bauhaus was more than just plans and charts creating regulated shapes and quirky tubular furniture. Bauhaus was the blueprint for a better way of life.

This was true even before the horrific experiences of the first world war that affirmed his resolve to look forward, not back; to cleanse the world of a dreadful legacy by focusing on a better, brighter future.

When the Bauhaus School was founded at Weimar in 1919 it was not merely a school of architecture and design, it was a revolutionary way of living, seeing and thinking, so much so that the local authority in Thuringia considered closing it down for being a religious cult.

The Bauhaus philosophy even extended to a diet of vegetables whose constant stewing left a pungence hanging around the school and its occupants: Alma Mahler, who left the composer Gustav Mahler for Gropius, recalled that her chief recollection of Bauhaus was the overriding pong of garlic.

Even before Bauhaus and the war Gropius had demonstrated a vision out of step with his contemporaries, designing a shoe factory, the elegant Faguswerk in Alfeld-an-der-Leine, that showed a distinct, fully formed style featuring clean lines and large windows that allowed in as much light as possible for the benefit of the workers inside.

The war would only enhance these motivations, and affected Gropius profoundly. Among the first to be drafted in July 1914, he served on the Western Front for almost the entire duration of the conflict, witnessing unimaginable horrors from the earliest exchanges when one-third of his regiment was wiped out in an hour, to the last weeks when the collapse of a fortification in which he was stationed left him buried in rubble for three days before being rescued.

When he was demobbed and returned to civilian life he recalled how “a flash of lightning” had told him “the old stuff was out”. The world, every aspect of it, needed a fresh start and he would play his part.

In 1915 the outgoing principal of the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar had recommended Gropius as his successor and, once he was finally able to take up the role in 1919, he set about turning it into the Bauhaus school.

Convinced the route to a better world lay in design that paid attention to every aspect of life from buildings right down to the contents of the cutlery drawer, Gropius set about creating a revolutionary place of learning that would have a profound effect on the way the postwar world would come to look.

Basing his institution on principles derived from the medieval stonemasons’ guild Bauhütte, Gropius’s Bauhaus would become a community striving together for a common cause. Tutors – who included Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky – were addressed as “master” and the students were referred to as “apprentices” or “journeymen”. The first influx of students, many still shaven-headed from their war service, found an abandoned consignment of Russian military uniforms, dyed them in bright colours and began wearing them. They staged joyous weekend festivals celebrating peace and freedom featuring mass kite-flying and night-time lantern parades.

“Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future,” Gropius wrote in his Bauhaus manifesto, “which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”

Pure utopian ideals like these were unlikely to endure and by the time the school moved from Weimar to Dessau in 1926, into purpose-built premises designed by Gropius and paid for by a booming city with a progressively liberal mayor, the project had become a little more conventional due in part to the high demand for Bauhaus products.

Within a few years, Gropius’s worst fears for mankind were realised by the rise of Nazism. While he considered himself a patriotic German, Gropius was no Nazi, Hitler’s party stood for everything he abhorred. When they came to power in 1933 the free-spirited activities of the Bauhaus school were soon the focus of attention for a regime bent on rooting out what it regarded as degeneracy.

By then Gropius had moved away from the running of the school into private practice, his designs including forward-thinking housing estates in Dessau, Karlsruhe and Berlin, but before long troops were arriving at the school and herding Bauhaus apprentices into vans to be taken away for interrogation. Gropius saw no alternative but to leave Germany – his second wife Ide was convinced that had he stayed he would have ended up in a concentration camp – and made his way to Britain, arriving in London in 1934.

Gropius couldn’t take to Britain – “an inartistic country with unsalted vegetables, bony women and an eternally freezing draught” – and in 1936 left for the US.

Late in life, Gropius would recall contentedly the principles he had devised to found a remarkable school that became a revolutionary movement to change the world of design forever.

“Young people brimming over with new ideas and the desire to realise them flocked to us from home and abroad,” he reminisced in 1964, “not to design ‘correct’ table lamps, but to participate in a community that wanted to create a new man in a new environment.”