It was, according to one newspaper, “the party of the year”. Le Grand Divertissement à Versailles was a charity fashion show conceived to help raise funds to restore the Palace of Versailles to its former glory. However, the event, held on November 23, 1973, did more than just bring in some of the much-needed $60m. It gathered some of the world’s biggest celebrities to the Paris suburbs, pitted American and French luminaries of fashion against each other in what became known as The Battle of Versailles, and changed the industry for ever.

The event was the brainchild of Eleanor Lambert, the influential American fashion PR, who suggested the idea to Gérald van der Kemp, the head curator of the Musée National de Versailles, and the man in charge of the restoration.

It was the culmination of years of effort on Lambert’s part to promote American fashion. The Met Gala and New York Fashion Week were among her innovations, but the Battle of Versailles would finally see five top American designers – Oscar de la Renta, Stephen Burrows, Halston, Bill Blass, and Anne Klein – share the stage with five “kings” of French fashion – Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Cardin, Emanuel Ungaro, Marc Bohan for Christian Dior, and Hubert de Givenchy – in the very home of haute couture.

“Lambert had a vision for what she wanted the impact to be,” says Robin Givhan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Battle of Versailles: The Night American Fashion Stumbled into the Spotlight and Made History. “She wanted to raise the profile of the American designers, I’ll say internationally, but during that time Paris was what really mattered, it was the centre of fashion.”

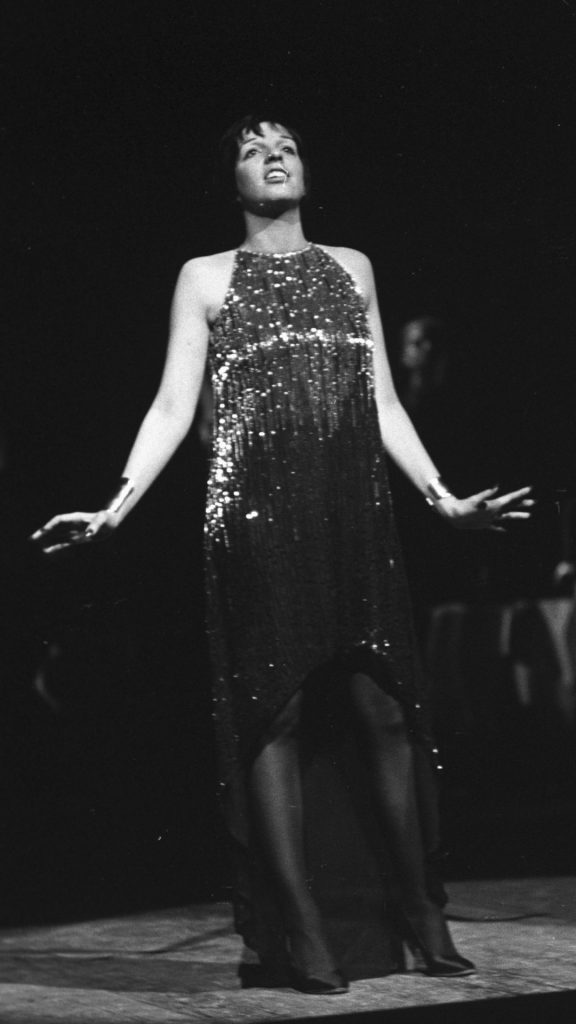

Lady Marie-Hélène de Rothschild was appointed honorary chairwoman, and persuaded the French president, Georges Pompidou, to sign off on the use of the palace’s opera house, Théâtre Gabriel, which was opened in 1770, for the show. The 700-strong guest list was a who’s who of the world’s social and artistic elite. The likes of Andy Warhol, Princess Grace of Monaco, Christina Onassis, the Duchess of Windsor and Elizabeth Taylor each paid £235 for a ticket. Josephine Baker opened the show for the French, Liza Minelli, hot off her Oscar win for Cabaret, performed for the USA.

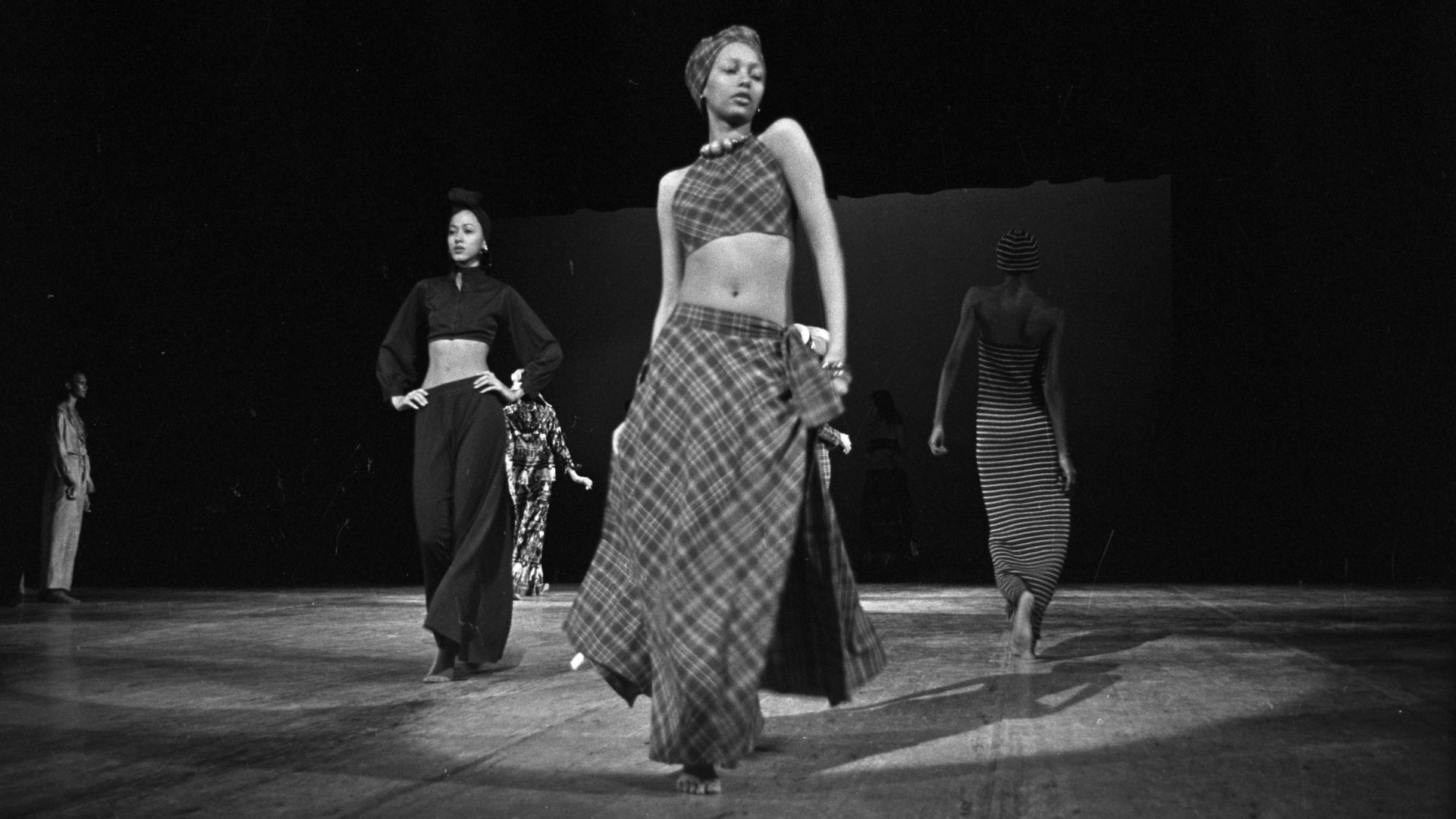

Of the 35 American models, 10 were black – Pat Cleveland, Bethann Hardison, Billie Blair, Jennifer Brice, Alva Chinn, Norma Jean Darden, Charlene Dash, Barbara Jackson, Ramona Saunders, and Amina Warsuma – while China Machado had been born in Shanghai. It was a level of diversity unknown in the industry at the time. By contrast, the French models were all white.

At 18, Brice was the youngest. Tall and thin – Burrows called her “a pencil” – she had been in the industry for just a few months. “It was the first time I’d left America,” she says. “I wish I’d brought a camera because there were so many beautiful memories. I was young and naive; I didn’t really realise where I was or what was going on.”

Four years older, Chinn was one of the so-called Halstonettes, a group of models who regularly worked with Halston. She also worked for Burrows and De la Renta. Despite being more experienced than Brice, the trip was still, she says, “a dream come true”.

However, when they arrived in Versailles, the Americans found their experience to be altogether more nightmarish. They were not provided with the basics. Food and water were scarce. There wasn’t even toilet paper in the bathrooms. The backstage crew members and theatre technicians – all French – strictly worked to rule. “Honestly, it felt as if we were unwanted guests,” says Chinn. “Théâtre Gabriel was damp and cold, the rehearsal time for us was virtually nil.”

It was 10pm on the night before the show that the Americans were finally able to take to the stage for a run-through. While the models practised their steps, tensions flared between the two sets of designers. Warsuma had been modelling since 1967, and had spent some time working in France, but she was shocked by the fraught atmosphere.

“I was on stage; I could hear people cursing in French. I could hear the Americans cussing back. It was like they were talking to their worst enemy. I could hear fighting and whatnot,” she said. “I didn’t dare turn around. I went in the back and Anne Klein was crying. The French just attacked them, asking ‘why are you here?’ They were totally unprepared for that.”

To add to the Americans’ woes, they found when they arrived that their sets were useless.

Joe Eula, the fashion illustrator who worked as Halston’s creative director, had produced a series of designs on fabric. However, due to a miscommunication, he had measured the material in feet, not metres. It was too short.

He rushed out to buy some more plain white fabric, and produced a makeshift sketch of the Eiffel Tower. It was minimalist, to say the least.

By contrast, the French show was far more opulent and expensive. While the Americans had a total of around $50,000 to spend, their hosts had about three times as much.

The French show spoke to the legacy and dominance of the country’s fashion industry. Accompanied by an orchestra and against a backdrop mimicking the lush forests around the palace, their show included a Cinderella-esque pumpkin carriage, a huge rocket ship, and a vintage 1930s Rolls-Royce. Their models moved gracefully but precisely around the stage. It was elaborate and ostentatious but, at the same time, it was disjointed and lacklustre. At two hours, it was also protracted.

“They were on there a long time and the audience got bored; it didn’t move them,” says Warsuma. “We had to make do with lights and a white background; it was kind of contemporary. It gave us a modern look, where the French had a period look.”

“The stripped-down sets for the Americans meant that the only things that were really on the stage were the models and the clothes,” says Givhan. “So, they were really able to capture all the attention.”

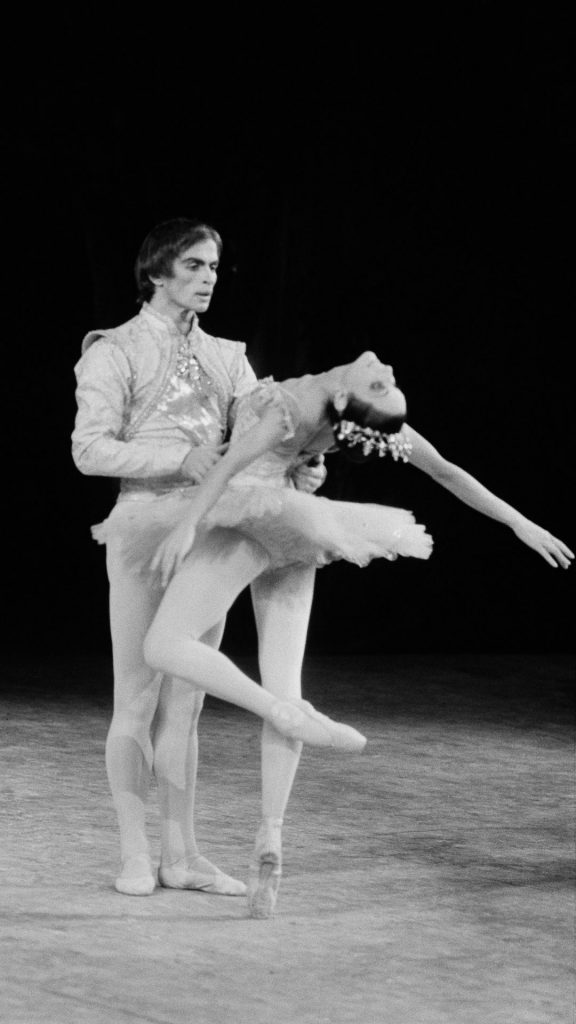

The French had performed to classical music such as the violin overture from Sergei Prokofiev’s Cinderella, while Nureyev danced a scene from Sleeping Beauty with Merle Park. By contrast, the Americans’ soundtrack included Al Green’s Love and Happiness, music from Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra, and the theme from the 1969 Luchino Visconti film The Damned. While their counterparts had been restrained, little more than living mannequins, the American models cut loose.

“We came out, it was altogether different music, it was more of a disco vibe, and I mean, we just walked the walk,” says Warsuma. “When we stopped, the audience just got up and threw their hats and whatever else they had in their hands up in the air, and they cheered. It was like we made that show – African American girls – and that’s why we’re in history.”

For Givhan, the models’ contribution was as important as that of the designers; after all, it was them who really sold the clothes. “French fashion was really about the clothing having this personality that the woman slipped into,” says Givhan, “whereas the American clothing was really secondary to the woman who was wearing it. That’s why I think the models were incredibly important.”

Black models had begun to make headway in the industry in the 1960s, but the Battle of Versailles accelerated the process.

“The show cemented something that was slowly happening,” says Marcellas Reynolds, the author of Supreme Models: Iconic Black Women Who Revolutionized Fashion. “Until the Battle of Versailles, Europeans had not substantively seen black models. The doors to Europe and haute couture were closed to black women. The Battle of Versailles changed that.”

The show also had a huge impact on the fashion industry. By introducing Europe’s cognoscenti to the quality and style of the American designers, the Battle of Versailles opened up the European market for the American designers.

“It really made the case for ready-to-wear as viable, creative, interesting, desirable fashion,” says Givhan, who thinks there was also a second, psychological benefit. “The other thing was that the American designers had always looked to the French to see what the next season should look like and then proceeded to copy them. I think it freed them so that they didn’t have to depend on them in that way.”

However, although the Battle of Versailles had a huge impact on the fashion industry, it wasn’t transformative for the individual American designers who took part. Several of the brands – Blass, Klein and Halston – in effect died with their owners, and although Burrows is still alive, his brand is to all intents and purposes defunct.

“Oscar de la Renta is really the outlier,” says Givhan. “After his passing, his brand is in the hands of two younger designers, and it’s still dressing the first lady and has a lot of red-carpet presence.” “It’s not one of those stories that necessarily has one of those big happy splashy endings for the individual participants,” she adds, “but I think that as a group they had a really important impact on the industry. They didn’t necessarily reap the benefits, but the next generation of designers did.”