When I first moved to the US, I came looking for the cliche of the American dream: pickup trucks and Friday night football, big skies and open roads, beers on porches and Sunday barbecues. I landed six months out from the 2012 election, spent $2,500 on an incredibly stupid car – a white 79 Corvette Stingray, which fell apart almost immediately – and moved to Hicksville, Ohio.

Hicksville was a charming, white picket fence town with about four traffic lights, a vast grain silo, and a world-class dive bar called Charlie’s. It’s again such a cliche but, sorry not sorry: the people were the friendliest I’ve ever met.

American football is close to the official religion of the Midwest, and on my first night everyone crowded the bar to explain the rules to me, sparking a lifelong obsession. I made friends that night I remain close with today. I go back whenever I can.

Sure, I fetishised it, like many foreigners who come to the US do. But I fell, and remain, hopelessly in love with the Midwest. It was freebase Americana. Which is why, on Wednesday last week at the Democratic National Convention, when Minnesota governor Tim Walz took the stage to accept the nomination to be Kamala Harris’s running mate, I was buzzing. He’s the Midwest incarnate.

That Wednesday night was absolute chaos. I arrived early at the United Center, the arena hosting the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. On my lanyard I had fully four tickets: one gold “special guest” pass, two silver “honoured guest” passes, and one, implausibly, identifying me as a ranking member of the Democratic Party’s National Executive Committee.

The things I had to do to obtain these shall remain secret, in order to maintain my dignity. I was there as a VIP, is my point. But still, I couldn’t get a fucking seat. I circumnavigated the arena several times on several floors, wheedling for entry at every door. I snuck up secret staircases. No luck: it was rammed to the rafters.

For several hours, I couldn’t even find standing room up in the gods. Eventually, after several exhausting hours, I ducked in the slipstream of an NBC producer into a reserved stand.

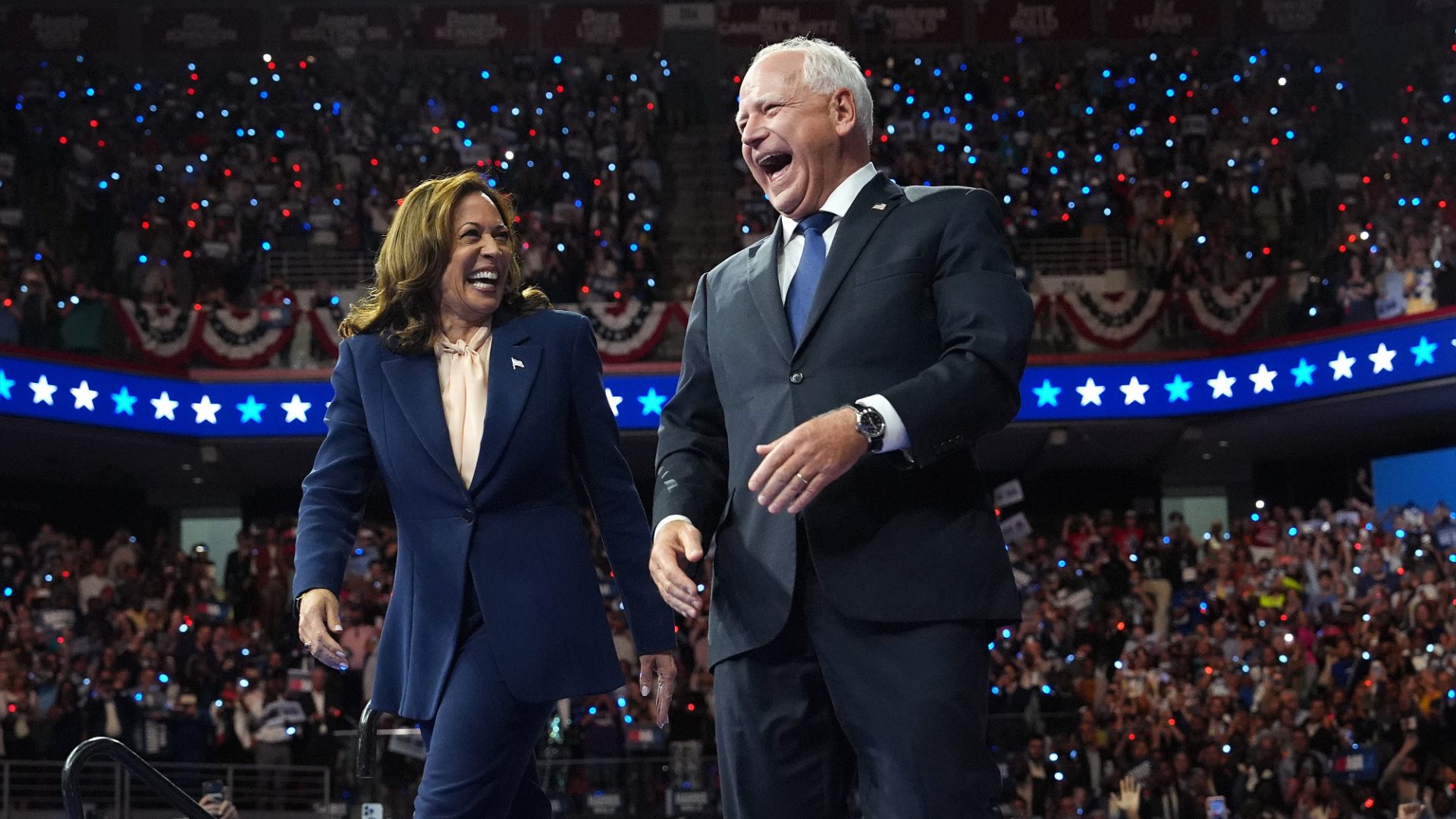

This wasn’t the final night of the convention; the Obamas headlined the night before, Kamala the night after. But the crowd was absolutely hyped. Walz is an unlikely rock star; but since Harris picked him a week or so earlier to be her running mate, he’s certainly become one.

It isn’t clear that the vice-presidential pick has a vast positive effect on presidential elections. The first two women to be veep picks – Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 and Sarah Palin in 2008 – failed to meaningfully swing female voters. Nor is there evidence, counter to conventional wisdom, that Mike Pence meaningfully swung evangelicals towards Donald Trump, according to Do Running Mates Matter? by political scientists Christopher Devine and Kyle Kopko. In a poll taken a month before the 2016 election in which Trump beat Hillary Clinton, more than 40% of Americans couldn’t name either vice-presidential nominee.

When running mates are chosen to carry their particular state, evidence suggests the effect is small. A study in the American Journal of Political Science showed that, historically, the vice-presidential nominee was good for a 0.3% bump in their home state and not much else.

Kennedy credited his 1960 victory to Lyndon Johnson’s support in the south, including his home state of Texas, but when they analysed data from the American National Election Studies’ survey, Kopko and Devine were surprised to find no evidence supporting this. Ultimately, they concluded voters vote for the top of the ticket, not the bottom.

Other analysis has put the home-state advantage higher – as much as 2.67 points in a Washington Post study, which is why many Democrats were keen for Harris to pick Josh Shapiro, the popular governor of the key swing state of Pennsylvania, where even half a percentage point could make a crucial difference.

But while the upsides of a pick are generally accepted to be pretty slim, the downsides can be considerable. The most famous example, George McGovern’s pick of Missouri senator Thomas Eagleton in 1972, is widely regarded to have sunk his campaign.

Soon after the convention, it emerged in the press that Eagleton had received electric shock therapy for depression; perhaps as much as the original pick, the weeks of dithering and negative coverage that led to the decision to dump Eagleton made McGovern look weak and indecisive.

John McCain later wrote that he regretted picking Palin as running mate in 2008; her constant faux pas on the campaign trail led to negative coverage and a downward-spiral approval rating.

Minnesota isn’t a swing state, though Walz’s popularity in the Midwest might help in Wisconsin and Michigan. But what Harris realised is there is another duty a vice-presidential pick can serve.

The momentum her campaign developed in its first month is more fragile than it appears. Her support is a loose confederation of warring tribes, including the donor-base of coastal centrists, an African-American power-bloc especially of black women in southern states (most importantly Georgia), and a meme army of online progressives.

Harris could have gone with Shapiro, or Mark Kelly, the former astronaut and senator for Arizona, and hoped they would move the margin. But neither would have achieved what Walz has done, which is to inject excitement all across that coalition.

His CV is almost too perfect. He served in the Army National Guard for 24 years, then went to state college in Nebraska on the GI bill. He became a teacher and moved to Mankato, Minnesota, where he taught social studies and geography. He coached the school football team – who made a surprise appearance to introduce him on stage – to a state championship, and was faculty advisor to the school’s gay-straight alliance.

“That family down the road,” he said in his convention speech, “they may not think like you do, they may not pray like you do. They may not love like you do. But they’re your neighbours. And you look out for them.”

He put in words something I experienced in the Midwest but could never quite encapsulate, the paradox between its natural conservatism and its compassion. “We respect our neighbours and the personal choices they make. And even if we wouldn’t make those same choices for ourselves, we’ve got a golden rule: mind your own damn business.”

Walz ran for Congress in 2006 and turned over a strong Republican district. He served six terms; in 2016, while his district voted overwhelmingly for Trump, they still re-elected him.

He served on the Veterans’ Affairs, Agriculture, Armed Services, and Infrastructure committees. In his first week in the House, he co-sponsored a bill to raise the minimum wage.

He ran for governor of Minnesota in 2018, and his record there is little short of incredible. With just a single-seat majority in the state house, he passed free school meals, college tuition for low-income students, and codified abortion rights into state law. He banned gay conversion therapy and passed legislation protecting trans rights.

He has a “100%” rating from Planned Parenthood and the ACLU, as well as the AFL-CIO and the Teamsters’ union. He’s a hunter who supported gun rights in Congress – earning him an A-grade rating from the NRA – but passed universal background checks in Minnesota after the Parkland mass shooting.

“I know guns. I’m a veteran. I’m a hunter. And I was a better shot than most Republicans in Congress, and I’ve got the trophies to prove it,” Walz told the packed convention hall.

He’s a canny political operator to boot: the “just weird” attack line is already among the most successful pieces of messaging in modern history, getting under Trump’s skin like nothing has before – and it was Walz who originally came up with it.

Here’s what’s most powerful about Walz though: he’s just a delight. He radiates an intangible Midwestern football dad energy, a powerfully kind masculinity that offers a stark contrast to Trump and JD Vance. If you told him you were hungry, I would bet good money he’d reply “Hi hungry, I’m Tim.”

He’d lend you his lawnmower. He has a dog named Scout. He’d shovel snow from your driveway.

Walz is the authentic avatar of small-town America that JD Vance desperately pretends to be. And because of that, the Republicans are rightly scared of him.

Facing a situation where, even before the convention, polling showed a huge gap between Vance (44% unfavourable) and Walz (25% unfavourable), they landed on an attack line saying Walz has misrepresented his military record.

But that’s a much riskier strategy for the GOP now, inviting as it does the comparison with Trump, who avoided serving in Vietnam with a doctor’s note about “bone spurs” in his feet and who called American war dead “losers” and “suckers”. Walz, meanwhile, is widely popular among veterans for his work on their behalf in Congress.

If you tried to create, in a laboratory, a candidate to put up against Vance, you couldn’t do better. “I haven’t given a lot of big speeches like this,” he said at the closing of his convention speech. “But I have given a lot of pep talks. So let me finish with this, team. It’s the fourth quarter. We’re down a field goal. But we’re on offence… and we’ve got the ball.”

And the crowd, waving thousands of signs saying “COACH WALZ”, went buckwild.