Of all the peoples in the world who suffered during the course of the spread of English across the globe over the last 400 years, one of the groups that suffered the most were undoubtedly the Moriori people of the Chatham Islands.

The Chatham Islands lie in the South Pacific, about 800km (430 nautical miles) east of the South Island of New Zealand. The New Zealanders who live

there today inhabit two of the islands, Chatham Island and the much smaller

Pitt Island. There are only about 700 inhabitants; guests at the hotel are informed that dinner is at 6pm, except that it’s later on Tuesdays when the chef plays rugby.

The islands are technically in the Western Hemisphere, lying just to the east of the International Date Line, but they are a part of New Zealand. They have their own time zone which is, rather quirkily, 45 minutes ahead of mainland New Zealand. (Visiting mainlanders have to remember that the 6pm TVNZ news comes on at 6.45pm.)

The Moriori were a Polynesian people who arrived on the islands from New Zealand some time before 1500AD, quite possibly by accident, and then seem to have lived there in total isolation for some centuries.

There were no natural materials on the Chathams which lent themselves readily to the construction of ocean-going boats, and so the Moriori stayed

where they were in total isolation from the rest of the world. Their language

and New Zealand Maori became significantly different from one another, though they still remained somewhat mutually intelligible.

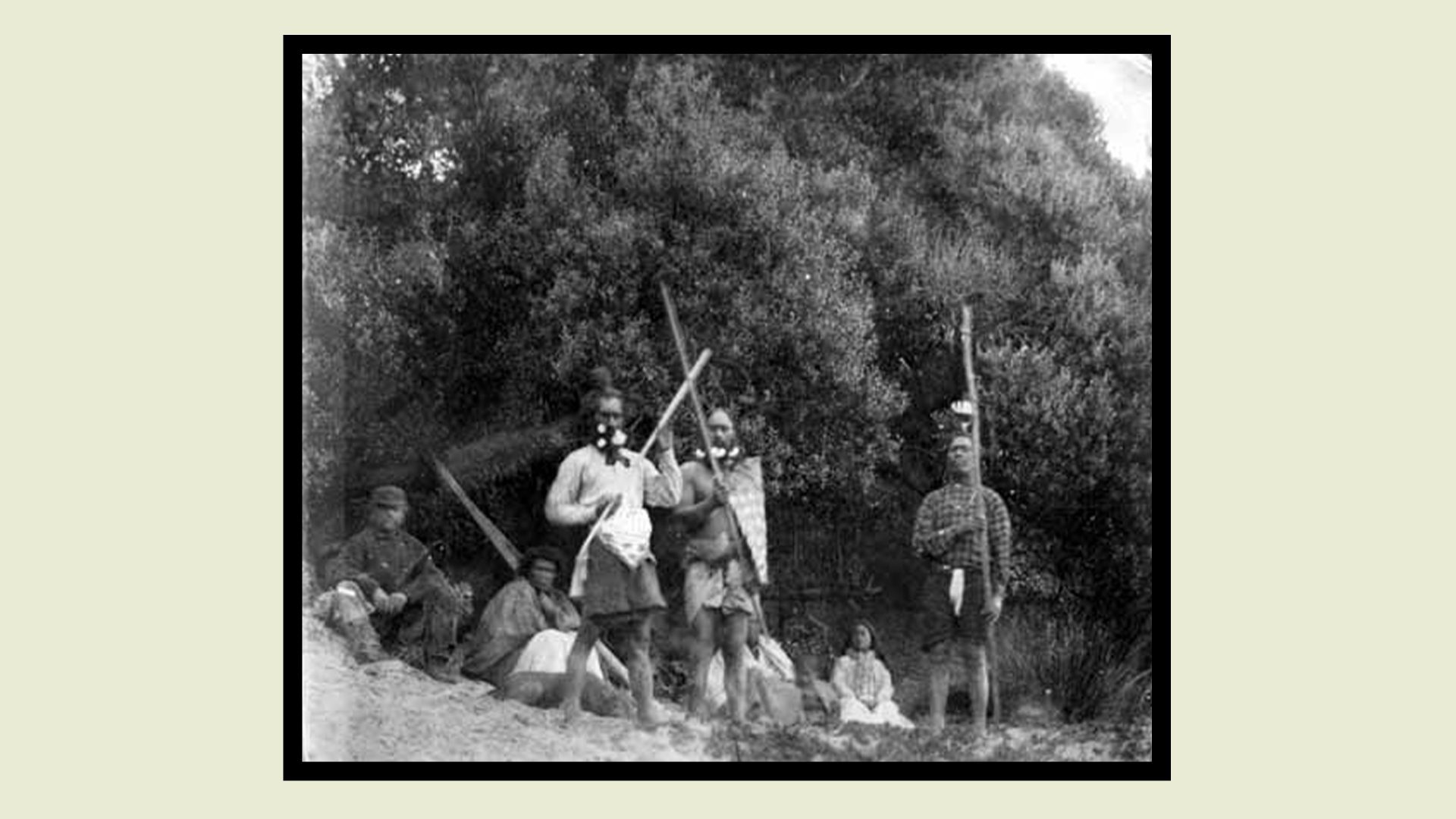

The Moriori developed a pacifist culture in which the only form of fighting permitted were duels between individuals which were stopped as soon as any blood was drawn.

As also happened on the New Zealand mainland, the Chathams were then visited by English speakers from Britain and Australia, many of them sealers and whalers, in the late 1700s. They brought diseases with them, which killed large numbers of Moriori. Then in 1835, the islanders suffered a genocidal invasion by about a thousand Maori, who arrived from the North

Island of New Zealand in a hijacked British vessel, bent on colonisation, and bearing European-manufactured guns.

The Moriori made the difficult decision to maintain their tradition of pacifism, and those who were not killed by the Maori were either removed from the islands or enslaved. The biggest slaughter occurred in early 1835, during the southern hemisphere autumn, when more than 300 of the 2,000 Moriori were killed by the mainland invaders.

The Moriori were then forbidden by the Maori to have children with each other; and within 30 years the Moriori population had fallen by 90% to fewer

than 200.

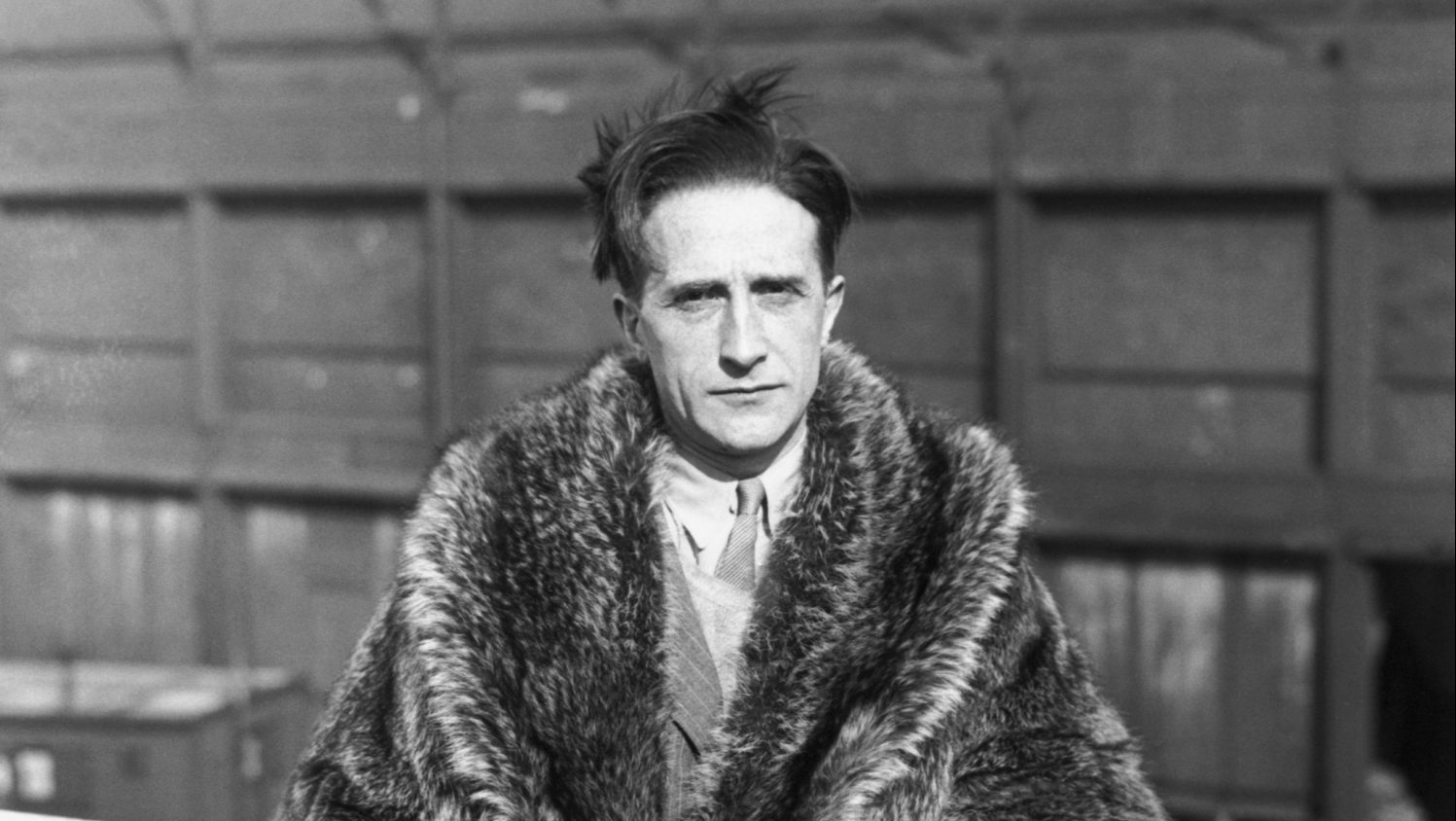

Slavery was ended by the British administrators in 1870, but by then no younger people were learning Moriori, and the last native speaker of the

language died in 1898. Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Baucke, who was born into a German-speaking missionary family on Chatham Island, was the last person who was able to speak Moriori; he died in Otorohanga on the North Island of New Zealand in 1931.

The last person of full Moriori descent died in 1933, though today there is something of a renaissance, with modern descendants of the Chatham Islands Moriori pushing for more recognition. Currently something like 700 New Zealanders identify themselves as Moriori.

MAINLAND

Main comes from an ancient Germanic adjective meaning ‘strong’, as in the

phrase “might and main”. Mainland is an interestingly relative term for a larger contiguous area of land as seen by inhabitants of outlying islands. The British talk of “Mainland Europe”; Shetlanders speak of “Mainland Britain”, and the biggest Shetland Island itself is called “Mainland”.