First, the invitations were withdrawn. One competition in Ireland, one in the Netherlands. Anna Geniushene worried there would be more. What if she were banned from the career-defining Cliburn piano competition in the US?

“After all those horrible things we didn’t know whether we would be allowed to enter this competition – even the preliminaries,” she said. “It’s a great honour to be here at all.”

Geniushene is a talented, passionate musician, a 31-year-old mother of one who is expecting her second child. She is also Russian. Which is why she felt lucky to be allowed to take up her last opportunity for a place in Texas at an international event held every four years and thus known as the “Olympics of the Piano”.

Since Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine in February, Russians and their music have lived under a cloud. Geography has rocked the arts, seeping malignly into the lives of musicians who more usually exist in the realm of solitary hard work and heavenly sounds.

Ukrainians used music as a rallying cry, with recordings of violins played in bunkers and piano etudes from the rubble of bombed houses, while western institutions talked of cancelling Russian musicians as they sought the limits of what’s appropriate in a state of war.

Can music transcend politics? Ask a Ukrainian who has lost family and home, and the answer might be no. But the prestigious Cliburn has kept the faith.

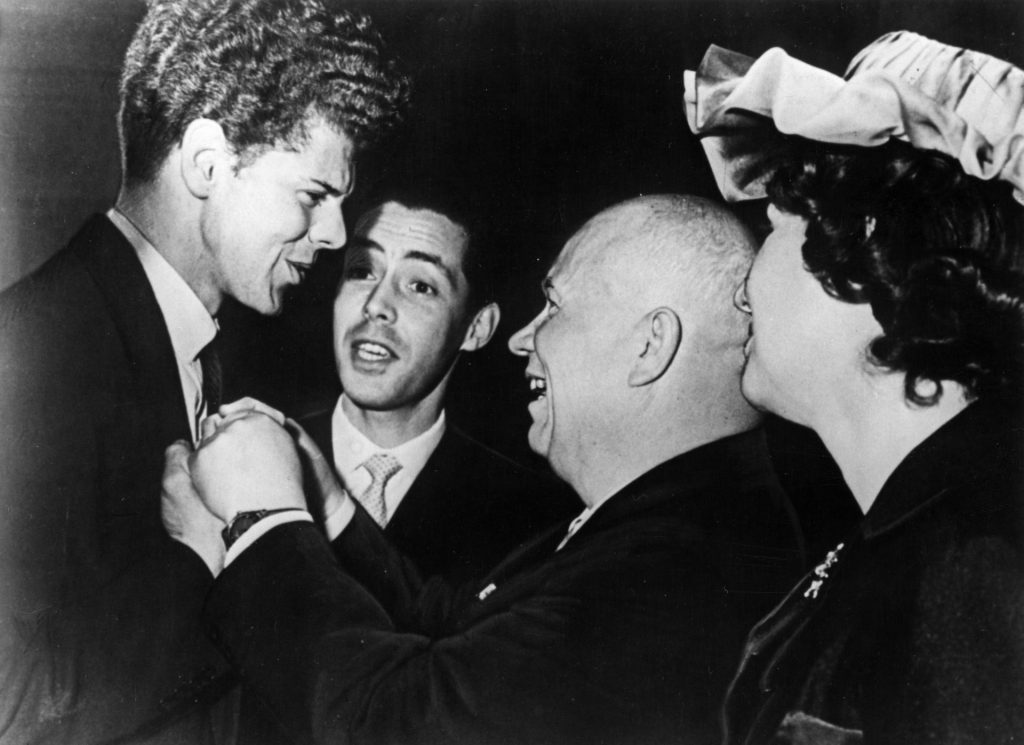

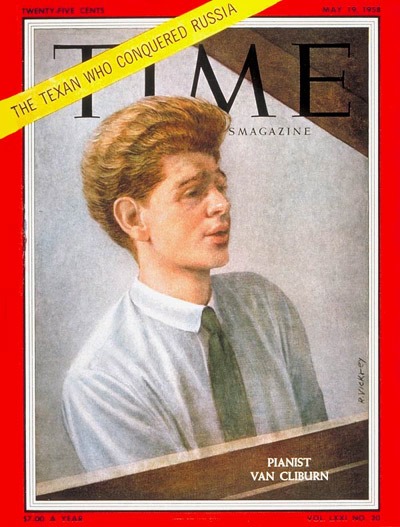

The thing about the Cliburn is its founder – the superstar Texan pianist Harvey Lavan “Van” Cliburn. He was all about music transcending politics. In 1958, at the height of the cold war, he went to Moscow for the first-ever edition of the Tchaikovsky piano competition, which had been set up as a platform for the Soviet Union to show its cultural dominance. He won, and the organisers had to ask the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, if they could give him the gold medal. “Is he the best?” he reportedly asked. “Then give him the gold medal.”

Cliburn completely spoiled the Soviets’ plans, but they loved him anyway. In a grainy video showing his extraordinary performance of Rachmaninoff’s Piano concerto no 3 in D minor, the Russian crowd explodes into ecstatic applause after the final chords. Cliburn and the conductor Kyrill Kondrashin hug. They walk back for their encores hand in hand, an embrace across enemy lines.

Despite tensions over rival space programmes and the Cuban missile crisis, Cliburn became a celebrity behind the Iron Curtain. TIME magazine put him on the cover – “The Texan who conquered Russia”. The history of the competition, founded in Cliburn’s home town of Fort Worth four years later, is studded with stellar Russian performers, some who defected. In 1987, Cliburn played at the Ronald Reagan-Mikhail Gorbachev Washington summit.

So while elsewhere Russian musical personalities were leaving their posts, Russian composers were being replaced on concert programmes and bookings for young Russian musicians were getting cancelled, Cliburn’s organisers announced they would continue to welcome Russian competitors. Six made it into the main field of 30, two of them – including Geniushene – progressing to the final. As did one pianist from Belarus – whose leader Alexander Lukashenko is an ally of Putin – together with a teenager from South Korea, a black American Harvard student and a highly rated Ukrainian, 28-year-old Dmytro Choni.

The decision set up an intriguing case study for those looking for political significance. Had the Cliburn called it wrong? With daily reports of Russian atrocities from the frontline in south-eastern Ukraine, would the crowds blame the young pianists by proxy? Would they be shunned by other competitors? How would Choni and the Russians interact?

There seemed to be no such qualms for the two couples I met in the audience at a packed-out public symposium with the nine competition judges. Ann Rice, a resident of Fort Worth where the competition took place, said firmly: “This kind of event is there to bring people together.” The crowd had cheers for everyone, while the Russians, Belarussians and Ukrainians were seen chatting together in Russian at gatherings.

There is no way this competition could discriminate against Russians. But the shadow of war loomed nevertheless. How could it not?

As the contest began, a Ukrainian priest in a suburb of nearby Dallas complained to the New York Times that the Cliburn wasn’t paying attention to “human suffering and public opinion”. A local journalist, Kristian Lin, who stood up and shouted Slava Ukraini! (Glory to Ukraine!) when Choni performed, worried that a Russian winner would feed Putin’s propaganda machine: “They had the chance to make a statement, and didn’t take it,” he complained to me.

But there’s also the argument that excluding them could feed into another propaganda narrative of victimisation by the “hysterical” West – one Putin uses to justify his aggression. Cliburn’s chief executive, Jacques Marquis, who had come under pressure over the Russian competitors, said he didn’t see how preventing a non-political twentysomething Russian from playing the piano would have any effect on the war in Ukraine.

The judges were keen to take this back to the personality of Cliburn, who, they said, always deflected political questions, making a point of connecting with the Russian people and showing that music and art could overcome fear. “In a way we are in a similar situation again – we feel this in Europe a bit more in that respect,” said German-born Swiss pianist Andreas Haefliger. “(And for this) we have a beautiful combination of finalists.”

The pianists were not asked to publicly disavow Russia’s actions, but it was clear any statement in favour would have made their position untenable. Most Russian competitors live abroad and oppose the invasion, some even taking part in anti-war protests. Ilya Shmukler, an eventual finalist, has spoken of guilt, shame and responsibility, while others played Ukrainian music in solidarity. But in competition they clammed up, tired of the distracting focus on politics, and knowing any political statement could bring unwanted attention.

“During the competition, I tried to stay focused on music, I let my emotional experience be reflected in the pieces I played, when appropriate,” Choni told me, carefully.

But the gruelling workload of the competition (140 minutes of recitals and three piano concertos for finalists) created a closeness and familiarity of sorts.

By the final weekend, they were too exhausted to say anything much, let alone stoke political fires. Except for Geniushene. Furious at the Russian invasion, the Moscow-born pianist had left the country to live in Vilnius with her Lithuanian husband, Lukas Geniusas – a former silver medallist in Russia’s Tchaikovsky competition, which was thrown out of the international federation of music competitions this year. The upheaval cost her. Even after being told she could compete, she considered withdrawing because of lost practice time from their escape and lack of suitable piano in her new home. In one performance, she referenced the war, wearing an example of Ukrainian embroidery called vishivanka.

“Right at the moment a lot of (Russian) musicians are making their statements – wearing the Ukrainian flag on dresses or whatever. I think our actions and our gestures say more than words right now – we’re residents of Lithuania and we’re not intending to go back to Russia until their oppression is over,” she said.

After the initial flurry, it’s becoming the general consensus that cancelling such young musicians is not in any way helpful to the Ukraine war effort. In fact, the Irish and Dutch organisers who first announced a ban on Russians recanted “because they realised it was a bit racist,” Geniushene said.

One of the most positive moves from this musical soul-searching has been the spotlight on Ukrainian composers, while declaring Tchaikovsky persona non grata is the silliest. Most Ukrainians don’t want it. Choni, whose parents had to flee and whose brother is involved in Ukraine’s defence, played Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No 3 in the final and was puzzled by efforts to ban rich and important piano repertoire by long-dead composers. Ukraine’s 2013 Cliburn winner, Vadym Kholodenko, may have railed against Rachmaninoff as he desperately tried to evacuate his parents from Kyiv, but has no plans to stop playing music from the expansive composer.

Nor does Geniushene, however angry she is at Putin. “My main role as a musician is not to stop playing Russian music despite the fact that all these horrible things are happening,” she said. “Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Prokofiev, Rachmaninoff are not responsible for the current political situation and the current aggression. If they were alive they would have been making statements of their own.

“I know that a lot of people are waiting for Russian people to walk in the streets, speak out, make statements,” Geniushene added. “But they can’t really do it for safety reasons. You would definitely go to jail and you wouldn’t have any idea when you would be out. This has happened to my friends.”

Yet even when politics is studiously avoided, it affects the conversation. When Shmukler explains why he chose to live in the US three years ago, for instance: “The atmosphere is more free and the mood in general in this country is excellent. Everything is so positive.”

In Fort Worth, contradictions bubbled below the surface as a taxi driver raving about the peacekeeping role of guns contrasted with the classical music fever that gripped the town in a state better known for cattle and oil. In cafes, hotels and in the square, people asked, “Are you here for the Cliburn?”

The 60-year-old competition inspires many, including the 600 volunteers who help out, driving guests from the airport, organising children’s events and hosting the 30 competitors in their houses for weeks, as they play the Steinways delivered to each house at all hours of the day. The youngest competitor, South Korea’s outstanding Yunchan Lim, said the highlight of the competition was being able to play for 12 hours a day, until 4am, without anyone complaining, as they did at his apartment block in Seoul.

Russia’s Elizaveta Klyuchereva, a multiple competition-winner who has performed with the Kharkhiv Philharmonic but succumbed in the early rounds here, enthused about the emotional warmth of the Cliburn: “To come to this competition is already a dream. So many legendary pianists played here, in these halls.” The hosts talk about working in loco parentis, and having to comfort their charges in their darkest moments, without any thought to their nationality.

And so it was, when Shmukler came on to play Grieg’s piano concerto no 1 in the final, the cheers went up not only when they said his name, but when they said “from Russia”. It was almost as if the crowd were proud to be offering a safe space in turbulent times.

Uladzislau Khandohi, from Belarus, had a fan group at the final who told everyone who would listen that he should win. When Geniushene completed a barnstorming performance of Tchaikovsky’s Piano concerto No 1 in the final, of which Gramophone magazine’s critic, Jed Distler, said: “I couldn’t help but equate Anna Geniushene’s seasoned pianism to Cliburn at his best”, the crowd erupted in whoops and cheers. After Klyuchereva’s energetic lunchtime performance of Symphonic Metamorphosis on Die Fledermaus (Strauss-Godorsky), which she finished with a disappointed shrug, several people made sure to compliment her.

But none of this wished the war away, and a powerful reminder of this was when a woman in blue rushed up to the stage and handed Choni a bunch of sunflowers after his engaging performance of Beethoven’s third piano concerto. Before the winners were announced, Kholodenko came on to the stage. As the crowd realised he was playing the Ukrainian national anthem, everyone rose – including the Russians and those who still study in Moscow.

When Choni was announced as the bronze medallist, the cheers were as if he had won. When Geniushene won silver and joined him onstage, they hugged. Sixty-four years after Cliburn hugged a startled Russian conductor, another symbolic embrace across enemy lines.

The winner was Lim, whose performance of Rachmaninoff’s Third was so accomplished it made Marin Alsop, head judge as well as conductor for the final, cry. Earlier, with the artlessness of an 18-year-old who said he would really prefer to live on a mountain with his piano, he had shrugged off his standing ovation and callbacks, saying, “I only entered the competition to see how I would measure up against the adults. Now I realise that I have a lot more work to do to become good. I’m disappointed.” Here was someone as far from the outside world of politics as it’s possible to be.

In the end, it was for Clayton Stephenson, Cliburn’s first ever black finalist, son of a Chinese single mother and dependent on grants for much of his early career, to lay it all out. Discussing his time at a junior music camp in Europe at the age of 12, he recounted how awkward everyone felt at first: “We were from China, Russia, Italy, Germany, the US. We didn’t speak the same language. The second day we all had a go in the practice room and as soon as someone started playing the piano, the Chinese kid went to the German kid and said ‘hey we play the same thing’. Suddenly we could communicate.”

That’s how music unites. “It makes me a more rounded person,” Stephenson told me. “Artists are not separated from the world.”

When I bump into the pianist Rico Gulda, one of the Cliburn judges, on our lengthy flight home to Europe, we discuss whether art can really transcend politics. “Not completely,” he mused. “But it can help cross divides. And that’s what we need now.”