We cannot be sure of the outcome of the French presidential election, but we can be sure that there are now two Frances. The first round of the contest pitted generation against generation, metropolitan areas against smaller towns and the countryside, the blue-collar against the better-off.

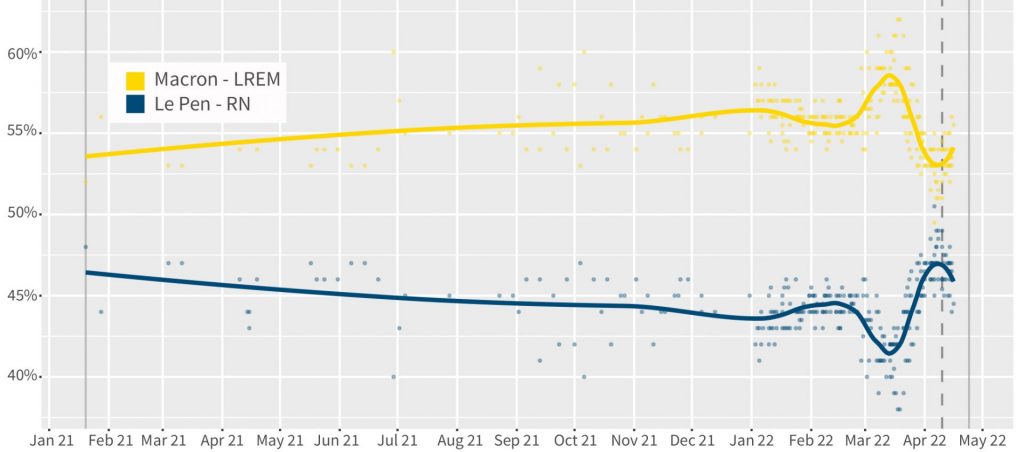

But which of the two Frances will prevail on April 24? Over the last 20 years, a presidential run-off between a far-right candidate and anyone else would have delivered a certain, clear victory to the latter. In 2022, the outcome is uncertain and unclear. It will be tight.

The answer will lie in the destiny of the first-round votes cast for a third candidate. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, veteran leader of La France Insoumise (Indomitable France) narrowly missed the second round by only 421,000 votes out of the 35.1 million cast. Macron and Le Pen must tap into his seven million votes – mainly from young and well-educated voters – to win the run-off.

For many Mélenchon voters, it is a choice between a headache and a toothache. Huge numbers will abstain because they hesitate between fear of Marine Le Pen, and detestation, even hatred, for Emmanuel Macron.

After five years of crises, the young optimistic president appears to his opponents as disconnected from real life. His five-year term has been punctuated with dismissive phrases about the working class, the unemployed and those who oppose him – “people who are nothing”, “refractory Gauls”, a “desire to piss off the unvaccinated”. Despite a “whatever the cost” policy deployed during the pandemic, an XXL welfare state that has made it possible to safeguard the economy by providing state-guaranteed loans, partial unemployment and aid of all kinds, economic policy for five years has been perceived as helping the wealthy.

A portrait has emerged of Macron as a haughty, arrogant novice, a “president of the rich”. There are echoes of Theresa May in 2017, in that the proposal from his manifesto which is most discussed is raising the pension age from 62 to 65. There has been damage, too, from McKinseygate, the revelation that the government has paid between €400m and €1bn (£330m to £830m) to the consultancy firm to help it evaluate and develop policy. Meanwhile, Macron’s habit of pressing through contested reforms by circumventing intermediary bodies like parliamentarians and trade unions has revealed an apparent preference for exercising power alone.

The war in Ukraine, while Macron is also holding the French presidency of the Council of the European Union, has monopolised his timetable. He only declared his candidacy for the presidency 48 hours before the deadline, and with the exception of one huge rally and two Q&A sessions with rather favourable audiences, the candidate hardly campaigned in the first round.

The French appeared grateful to him at the beginning of the crisis for so many efforts made in the service of peace. But his diplomatic efforts did not lead to any visible progress, and now opinion has changed. Was Macron trying to dodge a confrontation with the voters, did the war serve as a shield for him once his popularity reached record highs during March? Why did he refuse a televised debate against his competitors before the first round? The accusation of contempt and arrogance sets in again.

Yet at the start of the final week of campaigning, Macron still led the polls by an average of 9%. It shows that despite all of her attempts at whitewashing, there is still widespread fear of the far right embodied by Le Pen.

Le Pen relies on the fact that many ordinary workers no longer believe in the left. The Communist party is dying, the Socialist party has betrayed the expectations of the most deprived. Le Pen calls herself the loudspeaker of the voiceless to defend the most vulnerable French people. She rarely forgets, too, to denounce immigration, which she sees as a drain on the national budget, or to denounce Brussels, which takes from the French their decision-making power.

In 2017, Le Pen made it to the second step of the podium in the presidential final despite a manifesto that promised to give up the common European currency and leave the European Union. But during the traditional debate between both incumbents before the final round of voting, the National Rally candidate looked confused and adopted an unpresidential aggressiveness. The debate was a disaster and sealed her defeat, by 66% to 34%.

During the intervening five years, Le Pen has operated a meticulous refocusing. No more Frexit from Europe. No more refusing to pay off French debts. A welcome wagon rolled out to politicians from the traditional right. A new positioning as being not of the right or far right, but on the side of the small against the powerful.

The revolt of the gilets jaunes in November 2018, which she hailed as an authentic popular movement, helped to set her course. She then used the pandemic to criticise what she called “the government’s authoritarian policies”, including compulsory vaccination for caregivers.

Yet in the run-off, Le Pen won the battle of the right by concentrating on social issues and the cost of living crisis. Her rival Éric Zemmour, the journalist and TV host whose own manifesto spoke mostly of the restoration of French identity, lashed out at this as a “leftist” programme.

In fact, Zemmour’s rise in early polling helped her to appear less dangerous and worrying. The more outrageous he was, the more Le Pen appeared moderate. The more he focused on defending identity, the more she persisted in talking only about gas prices and the burden of inflation on working France. And each time she was asked about the Zemmour threat to her own campaign, she responded with the same sentence – “I have the calm of an old soldier”. Coolness, control, the long view. Far from proving a setback, Zemmour’s candidacy actually provided Le Pen with the narrative she was missing.

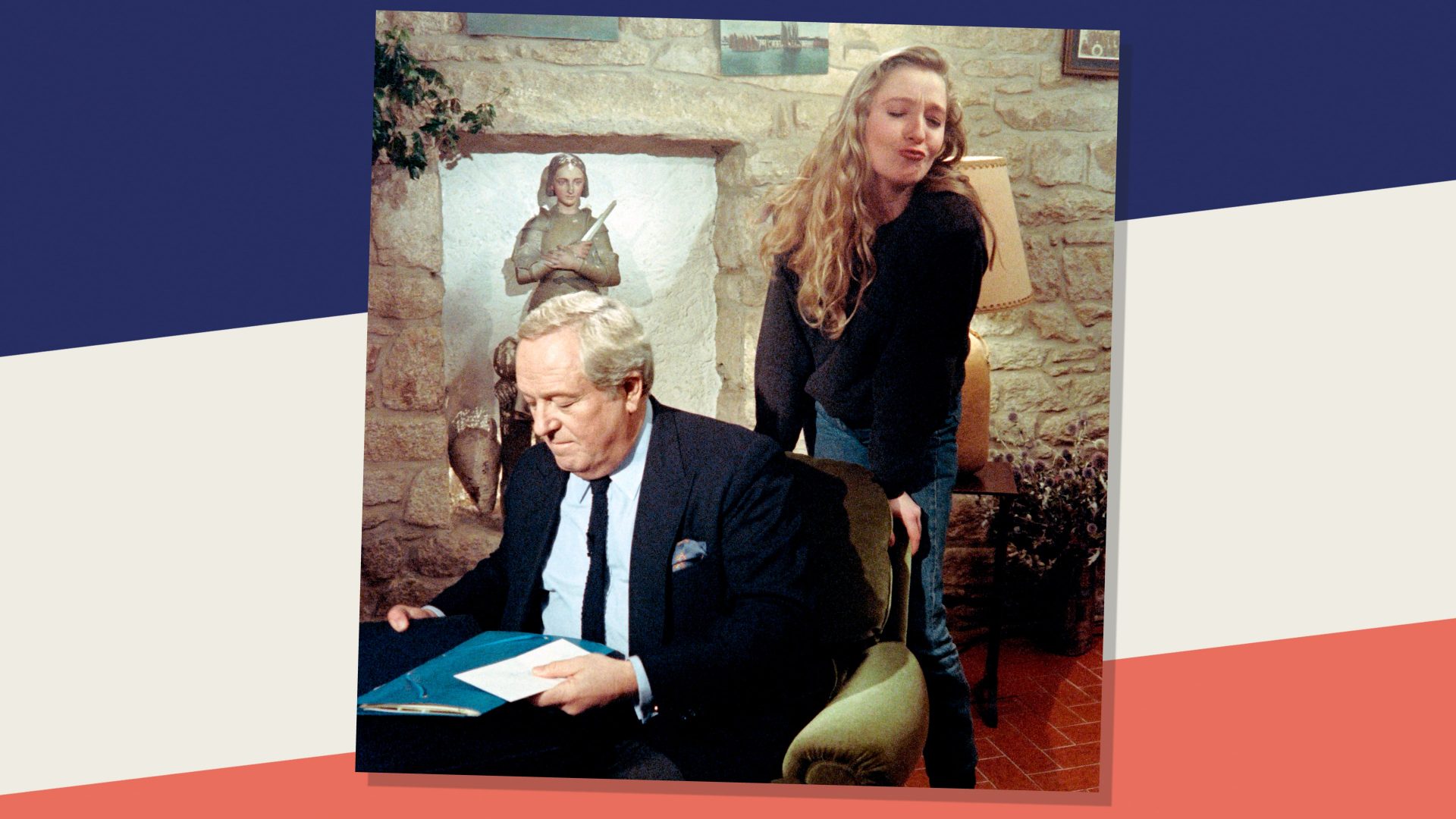

Nowhere was this shown better than in the intimate, confessional part at the end of her speech during her presidential convention. Le Pen spoke of her personal evolution, her early life in the shadow of her father, then raising three children alone. This staging allowed working-class supporters to identify with a privileged heiress; someone like them, in a way. It was a tour de force in terms of political communication. Forget the old Le Pen brand, now Marine, as her supporters call her, is coming forward. She has managed to shake off her well-recorded sympathies for Vladimir Putin – she had confessed her “admiration” for the master of the Kremlin a few years ago in a Russian newspaper.

She did not oppose Macron’s help for refugees to take shelter from the Russian aggression, again drawing a line between herself and Zemmour, who saw his polling drain away once he opposed the reception of Ukrainian refugees on French soil.

Five years ago, Marine Le Pen was seen as disturbing and dangerous. She struggled to appear close to people. She now poses for selfies, wears pastel colours, smiles on her posters and campaign leaflets. Above all, writes the political analyst Raphaël Llorca, she has won “the battle of credibility. In 2022, twice as many voters believe she has what it takes to be president than in 2017.”

The day after the first round, Macron rushed to make up for lost time. One day in the north, another in the east, then in a Channel harbour; not forgetting interviews with the morning radio shows and the evening television news. This brought him into contact with supporters of his rivals and gave rise to some shouting matches that were relentlessly aired on France’s four all-news channels and on social networks. These almost theatrical exchanges were a catharsis of the anger at him that is so often expressed, though Macron’s campaign team believe they help to clear the air.

Meanwhile, Le Pen was in the process of trying to look like a president, with two press conferences. One was on the big institutions and the “referendum revolution” in which she proposes to offer the French a vote on issues like the restoration of the death penalty and precedence for French nationals over migrants when it comes to jobs, welfare and housing. The other was on international relations, and managed not to mention the war in Ukraine. Finally, there was a rally in which she appealed for abstainers in the first round to come into her tent.

On April 10, more than one in two French people chose to vote for far-right or far-left candidates. The traditional parties that dominated French political life have been almost erased. France has just experienced an earthquake, like Brexit in the UK. But here, there is a second round. Who will seize its second chance?

Valérie Nataf is a writer and broadcaster, most notably for the French TV station TF1