Rejoice, fellow Remainers, for we have a new convert among our ranks – at least, we sort of do. Get ready to welcome to the ranks of Brexit realists none other than Nigel Farage himself, who admitted on Newsnight last week that “Brexit has failed”, hasn’t delivered any economic benefits, and that it had been “mismanaged… totally”.

Puzzlingly, this outburst was not immediately followed by an abject apology for Farage’s own outsized role in leading us to this outcome. Nor did he appear with a rucksack and a one-way ticket, intending to honour his 2017 pledge that if Brexit turned out to be a disaster, “I’ll go and live abroad, I’ll go and live somewhere else.”

Instead, Farage seemed to say – with something approaching absolute conviction – none of that failure was his fault. It’s all on the government.

Real Brexit is very much the new Real Communism. Those determined to defend the concept can’t (or won’t) actually say what they’d have done differently, but they will adamantly tell you that, just because it’s all gone wrong, it doesn’t mean it was a bad idea.

With Brexit this is an even tougher sell than with communism. What has gone wrong since has done so in pretty much exactly the ways that almost every expert warned it would. Brexiteers also got “their” version of Brexit: no compromises by staying in the single market or the customs union. Out meant out.

Then Liz Truss attempted to deliver the post-Brexit economy Farage has been talking up for years – deregulation, small state, low-tax libertarianism. It exploded on contact with reality.

Yet instead of accepting that the idea of leaving the EU, doing our own thing, and the rest of the world just letting us do as we liked was always an idiotic fantasy, the Farages of the world just sit and scold others for failing to deliver. It’s a process roughly as effective as chastising the guy in your corner shop for selling you a losing lottery ticket, when you wanted one that won.

Farage is hardly alone in his bizarre inability to see the connection between his own actions and their consequences. In the last week or two, you could barely check the news without seeing some new manifestation of the phenomenon.

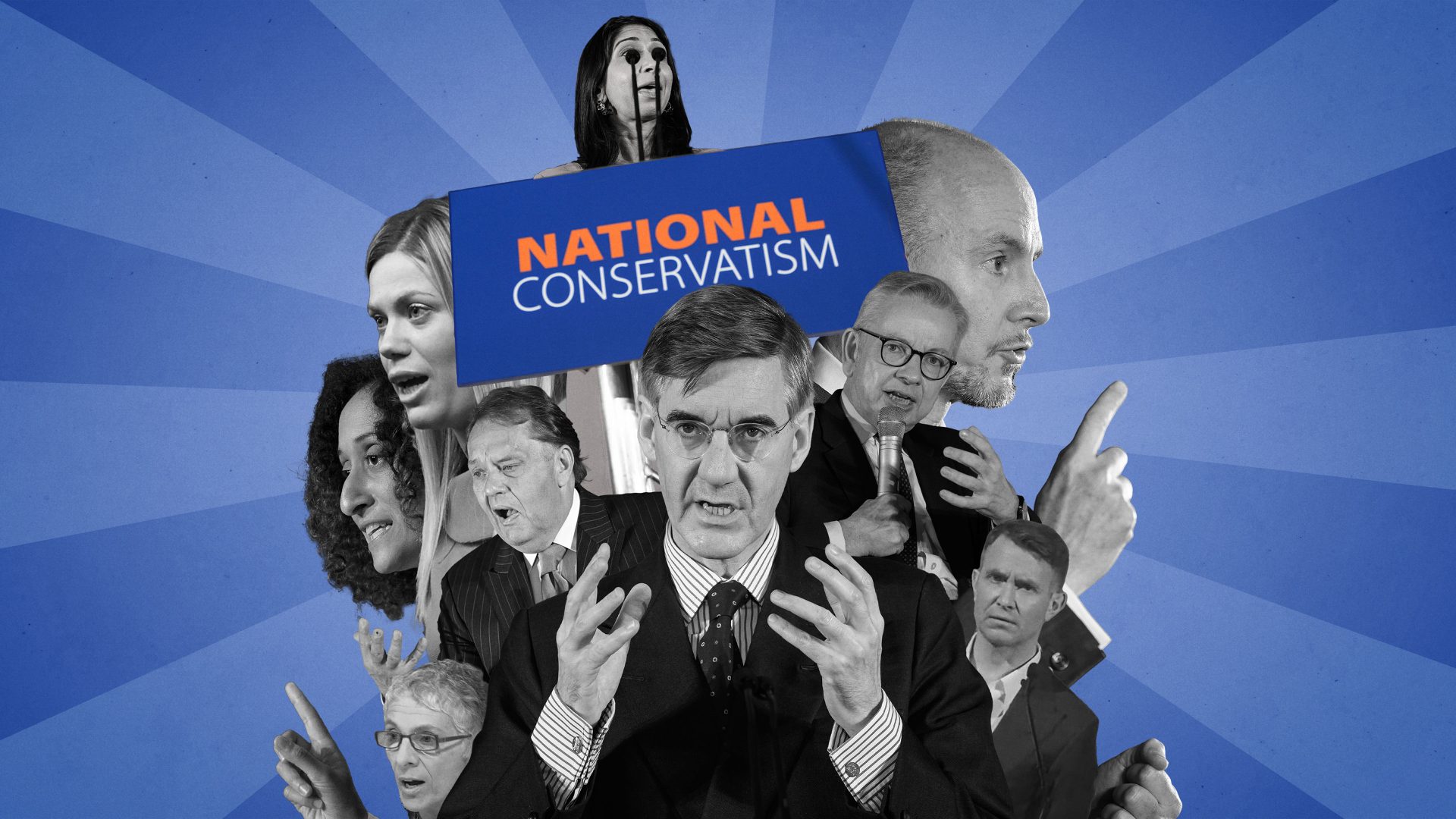

Watching last week’s National Conservatism Conference was an experience almost as surreal as it was disturbing. As Martin Fletcher explains elsewhere in this edition, one of the things that struck you most was how speaker after speaker sounded so very, very whiny, like people who have somehow been left behind or left out.

The reality couldn’t be more different. The conference was attended by multiple cabinet ministers, and largely chimed with the lines those ministers repeat at the dispatch box – this is not a government unwilling to engage in the culture wars.

The Conservative Party has been in government for 13 years, and the pro-Brexit wing of said party has been in power for seven. Brexiteers got exactly the hard Brexit that they wanted – we are out of the single market and the customs union.

The people on stage at the convention aren’t just the elite, they are the governing elite – and yet clearly they do not feel like this is the case.

This doesn’t feel like an isolated phenomenon, though. Republicans in the US talk as if they are isolated from power, despite having held the presidency from 2016 to 2020 and holding a two-thirds majority on the Supreme Court. Republicans have more governors than Democrats, and hold nine more state legislatures too – and yet they talk as if they are an insurgent movement.

There is a similar trend on the left, too. Former Corbyn aides and friendly commentators now talk as if they never actually ran the party, never got a chance to offer what they wanted. In reality, Corbyn was elected Labour leader by a landslide, twice, and after 2016 had a cabinet almost entirely composed of loyalists.

The “saboteurs” the faithful like to talk about undermining the 2017 election had all left long before the 2019 election, and its far more catastrophic result. But to hear a recent history from said loyalists, you would imagine Jeremy Corbyn had never really had a chance to lead – he was undermined from within.

This disconnection between political leaders and responsibility for their actions feels at least somewhat new. Tony Blair might have led the country to a catastrophic war in Iraq, but in its aftermath he did not try to shape it as something he had been forced into because the US was going to go anyway.

Similarly, David Cameron didn’t appear to rail against the Brexit referendum that his backbenchers had connived him into pledging, even as he proved woefully unable to contain the demons he had unleashed.

The disconnect feels to have happened in the years since 2016, though likely not as a direct consequence of That Vote.

There is a telling line in Ed Miliband’s resignation speech after his defeat in the 2015 election: “I take absolute and total responsibility for the result and our defeat at this election.”

It is not a sentiment his successor deigned to repeat during his own, short, resignation address in 2019.

What all of these trends have in common is an increasing sense from the people running the show that someone else is really in charge. This is a road that usually leads quickly to conspiratorial destinations.

If elected governments aren’t running the country, then is someone else? Is there some globalist plot actually running the show? Once people start asking these kinds of questions, they usually find answers that feature some combination of George Soros, the Rothschilds, the Jews, or the World Economic Forum (of Davos fame).

It is rare for people who have actually run political parties – and especially actual governments – to go down such routes, but it is striking when the people who have been in positions of political influence and power clearly don’t feel that’s the case.

Outside the world of conspiracy and into the world of mundane reality, there is no cabal stopping governments doing what they want, or forcing Britain to be woke against its will. The reality is that doing stuff is much more difficult than most of us realise. Things we imagine should be simple and quick rarely are.

Think about the last time you had a job that required workmen, for example – perhaps a home extension or a kitchen remodelling. It’s a fairly simple job, right? How long could it take? It’s hardly restoring the Sistine Chapel.

And then reality hits. It turns out the joists are rotten, or the plumber gets sick, and then the schedule has been pushed back and clashes with another job. The supplier has sent the wrong kitchen units over and the right ones are now out of stock. You rapidly realise that you are now in week 14 of what should have been a three-week job – and you’re still not done.

Running an organisation is like that, but turned up to 11. Things that seem like a good idea have been tried before, and failed. Different people have different priorities, and you only have so many people and so many hours. All of that is before ideology comes into it at all – or competing for limited amounts of money.

When you’re running a political organisation, you are surrounded by ambitious people who want to push their own particular agendas. There is only so much political capital to spend, and everyone is competing for spending – meaning that every big policy proposal you make will necessarily rule out several more. Deciding what to do becomes fraught.

This ramps up again in government: if you’re in No 10, you’re at the mercy of departments, trying to pull levers of power at several removes. If you’re in a department, you’re subject to the whims of No 10 and the slide rule of the Treasury.

The second anything starts to actually be enacted, you also have to contend with the media, the Bank of England, the markets, vested business interests, activist groups, and more. However senior a figure you are in government, you will always be reckoning with other big beasts. There is pretty much no one who can get up in the morning and feel like they are genuinely the master of their universe. Everyone has a boss.

What seems worrying is that increasingly the people who have risen to the top politically seem to have forgotten that fact, and are so publicly sulking that their job is hard. Since when was doing anything worthwhile supposed to be easy?

The Farages of the world like to call up cosy images of Britain’s imagined, glorious, past – we must reclaim that kind of “can do” spirit, they insist. Except even as they say that, they have become so detached from reality that they haven’t realised they’re not only the ones that can do things, they’ve been the ones doing them for the last several years. It’s impossible to look at what you’ve done when you apparently can’t even realise it’s you that’s done it.