Leaning on the lectern in parliament this week, Lord David Frost seemed to be enjoying himself as he briefed colleagues on UK threats to trigger Article 16 of the Northern Ireland protocol and start the clock on this year’s Christmas Brexit Crisis.

“My Lords, I gently suggest that our European friends should stay calm and keep things in perspective,” he said, allowing himself a little smile as a few cheers and hear-hears rose from his appreciative audience. “They might remind themselves that no government and no country has a greater interest in stability and security in Northern Ireland and the Belfast Good Friday Agreement than this government. We’re hardly likely to proceed in a way that puts all that at risk.”

Across the Irish Sea, his words are likely to ring very hollow.

“Nobody thinks the British government’s actions are primarily out of concern for Northern Ireland because if they were, you wouldn’t go about it this way,” said Katy Hayward, professor of political sociology at Queen’s University Belfast. “That explains why tensions are so high… Even if you’re a unionist, pro-leave and you’re anxious about the protocol, you feel this sense of profound insecurity because you don’t trust the British government to defend Northern Ireland’s interests. If you look at what they’ve done in the past, including even drawing up the protocol, that would lead you to doubt that, ultimately, when all this is over Northern Ireland would be in a better place.”

The protocol, part of the EU-UK withdrawal agreement, prevents a hard Irish border by keeping Northern Ireland inside the EU’s single market for goods and drawing a customs border through the Irish Sea. Many unionists oppose it, saying it undermines Northern Ireland’s place in the union while some businesses say the extra red tape around GB-NI trade has caused difficulties.

The UK government says it can trigger Article 16 because it is a safeguard mechanism meant to be used when the protocol is leading to serious “economic, societal or environmental difficulties”. It says these criteria have been met. The EU has offered to drastically reduce the number of checks on goods travelling from GB to NI but the UK insists the protocol needs a more fundamental redrafting, including the removal of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) from its role as arbiter of EU law. This is a red line for the EU.

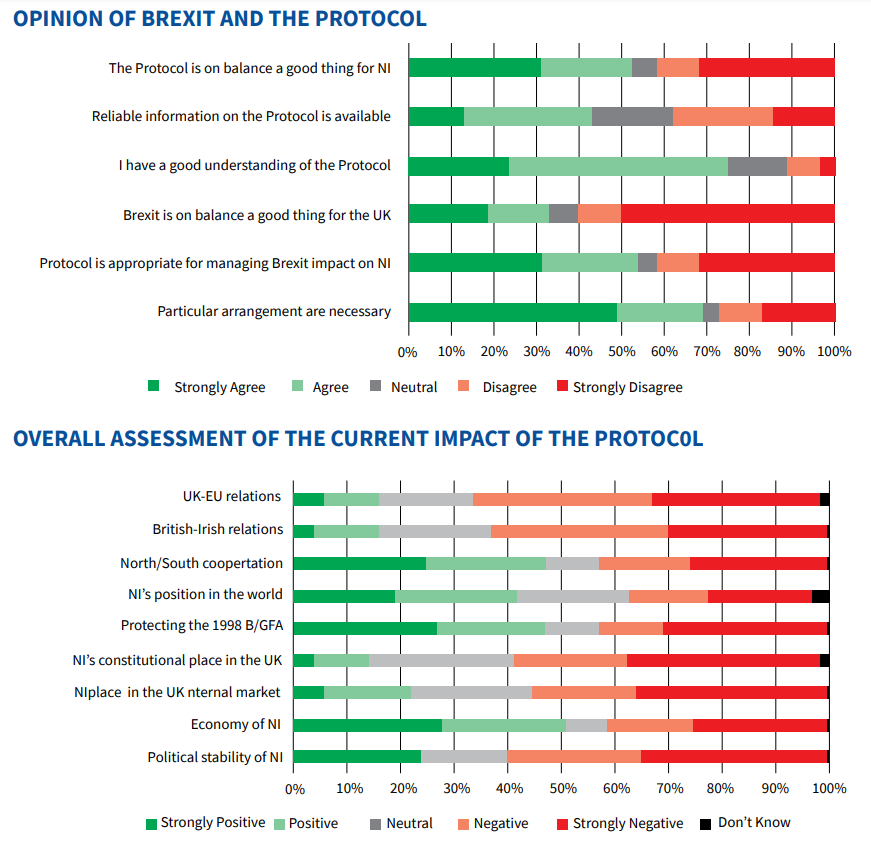

Hayward says an October survey in Northern Ireland found that 53% of those polled thought the government should not trigger Article 16. Of the 39% who said they should, most were from the unionist community, many of whom have always opposed the protocol. But as she points out, Article 16 does not allow for wholescale renegotiation.

“It’s not about suspending the whole thing or putting it in the bin and trying again. The purpose of safeguard measures is to fix something in order to make the overall agreement work better. But you have to be really specific about what you want to fix,” she said.

The lack of detail on this point makes Hayward wonder if the UK’s threat on Article 16 is a “politically motivated move rather than one that is first and foremost about relieving the economic situation in Northern Ireland”.

South of the border in Ireland, Neil McDonnell, chief executive of the Irish SME Association, says no one has a clue what the UK wants out of its future trading relations with the EU. He calls it a Schrödinger’s cat situation, with the UK wanting to be in the EU but also out of it.

“The goal here is perpetual conflict because that will appeal to a certain cohort of the Tory electorate and it almost becomes like “1984” where Oceania is at war with Eastasia and it has always been at war with Eastasia and the Tories keep getting re-elected but we don’t come to earth on a trading position. (Irish small businesses) don’t have the bandwidth to accommodate problems like this,” he said, adding that the uncertainty makes contingency planning almost impossible.

The Irish government is, however, trying to do just that while it urges its neighbour to step back from the brink. The risk for Irish businesses is that in the event of a suspension of the protocol goods might have to be controlled as they cross the Irish border or as they leave Ireland for the rest of the EU.

Tánaiste Leo Varadkar sounded like the tired parent of a recalcitrant teenager as he called on the UK not to jeopardize the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) brandished by prime minister Boris Johnson so gleefully last Christmas Eve. “You were part of negotiating it, you own it, it was hard-won,” Varadkar said. “It’s a mistake to think that, by escalating tensions, by withdrawing from any part of it or trying to withdraw from any part of it, that you’ll end up with a better deal. You won’t.”

The whole ECJ element also frustrates McDonnell. He wrote a letter to the UK ambassador to Ireland this week, saying none of ISME’s cross-border members had ever mentioned the ECJ as an issue. “Cynicism indicates that it isn’t a real issue for the UK. It’s an issue of convenience,” he said. Hayward says that in a recent survey on people’s priority concerns in Northern Ireland, the ECJ was “at the bottom of the pile”.

They are not alone in their doubts. Some commentators see this latest Brexit crisis as a handy distraction from the tsunami of corruption allegations washing over Westminster. Writer Will Hutton recently tweeted: “The Paterson affair breached the dam and a flood of latent criticism has broken over Johnson. His instinct will be to trigger Article 16 to save himself: plucky UK v over mighty EU. Expect a second flood of huge latent criticism: Brexit is broken. It needs fixing – not ever hardened.”

Pressure is also coming from the United States. After European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen met president Joe Biden in Washington, she said he agreed with her that it was important to stick to the protocol. And four members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee issued a statement, calling on the UK “to abandon this dangerous path, and to commit to implementing the Northern Ireland protocol in full.”

Talks are ongoing but neither side seems too optimistic. The EU’s Brexit commissioner, Maroš Šefčovič, has called Frost’s demands unrealistic while Frost accused the EU of threatening “massive and disproportionate retaliation”. The EU is said to be preparing a series of retaliatory measures up to and including the suspension of the TCA. McDonnell is worried.

“2019 was such a bad year in terms of people dreading what was on the way and then we finally got things over the line in 2020 and we thought we were on firmer ground and now the ground is shifting underneath people at the point when they are hoping to get out of jail post-pandemic,” he said.

“You could even see Irish businesses saying, “A plague on your houses, you want everything and you can’t have everything; there has to be a compromise’. It’s the absence of certainty… Your only solid contingency is to almost ignore the market, or say, ‘I’m just going to have to work on the basis that UK business is not going to be available or economical’.”

North of the border, there are other concerns as well. In recent weeks two buses have been hijacked and set on fire in protests apparently linked to the protocol and while fears of violence can often be overstated, Hayward says the real issue is the deeper damage being done to cross-community trust.

“The work I’ve done in the central border regions showed just how much people are seeing that those tensions – UK-EU, British-Irish, nationalist-unionist – are all filtering down to an environment that makes cross-community relations and cross-border cooperation more difficult,” she said. “That’s why I would have the greatest worry that these things do cause damage and the damage isn’t necessarily in terms of riots or interfaith violence. It’s more about how difficult it is to rebuild trust in relationships.”