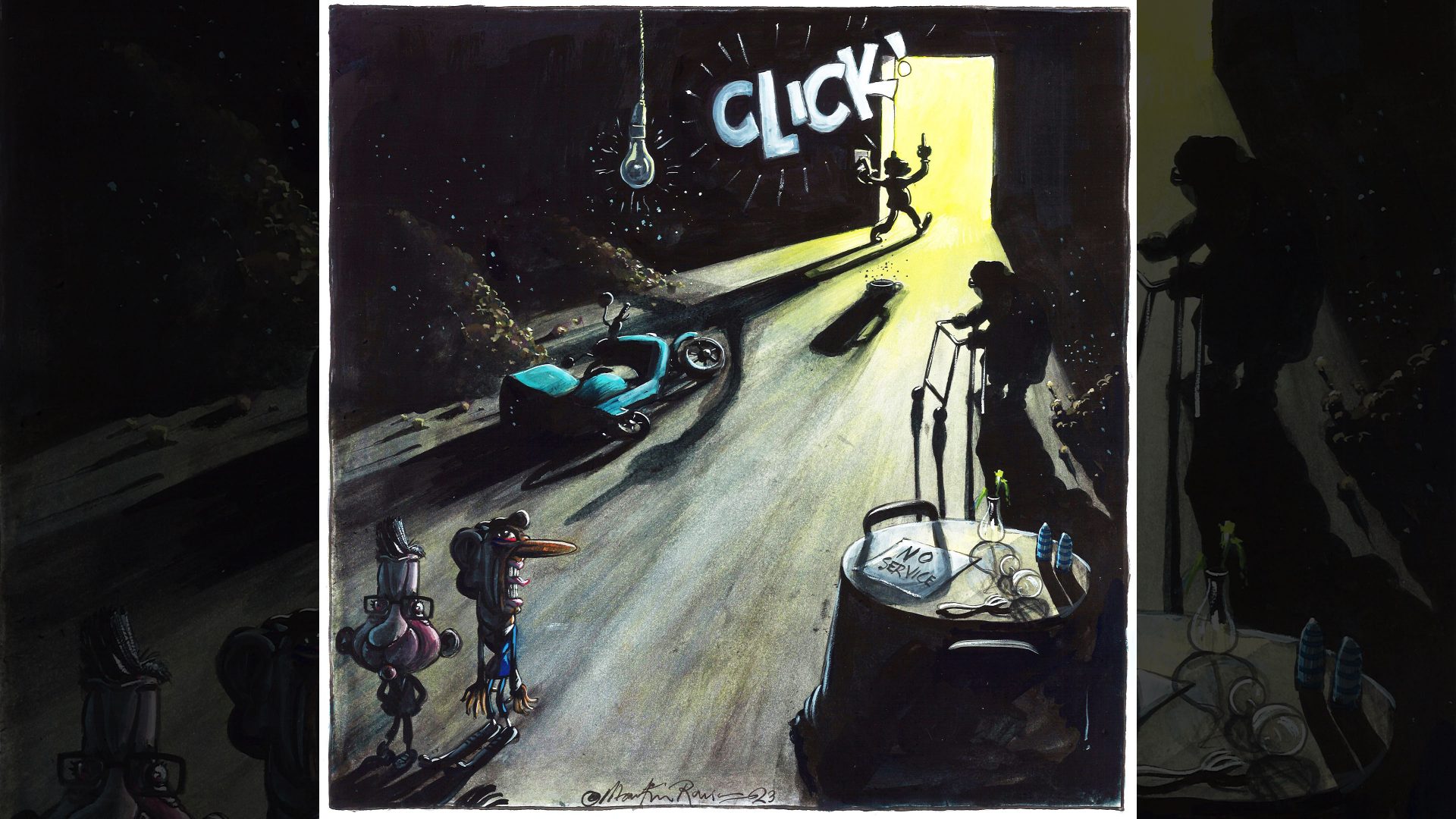

The NHS is in the midst of a perfect “polycrisis” – in which a decade of underfunding, the post-Covid demand surge, the post-Brexit skills shortage and double-digit inflation are starting to cause multiple, systemic meltdowns: of A&E departments, GP services, waiting lists and social care.

Hundreds of excess deaths per week are the result. But it’s likely, given what we know about how austerity in the 2010s eroded public health, that the long-term impact will be more severe.

For the Conservatives, however, it’s a poly-opportunity: to bash trade unions, promote private sector care, postpone reforms to social care and ultimately seed the ground for yet another attempt to promote an insurance-based model.

And it’s a crisis 20 years in the making. In 2002, the Wanless Report – a strategic overview commissioned by Gordon Brown – predicted that by 2022 the UK would need to increase total healthcare spending from 7.8% of GDP to 12.5%.

For that money, said former banker Derek Wanless, even if you executed NHS modernisation in the most costly and inefficient way imaginable, you could still achieve “safe, high-quality treatment; fast access; an integrated, joined-up system; comfortable hospital wards and a patient-centred service”.

Today we do indeed spend 12% of GDP on healthcare. But we’ve achieved none of what Wanless envisaged.

Health outcomes for major diseases, such as stroke and heart attack, are way poorer than in comparable countries. There are 7 million patients waiting more than 18 weeks for hospital treatment – the comparable figure was below 2 million 20 years ago. And though the philosophy of patient-centred care has taken hold, the ability to deliver it is collapsing.

It’s depressing to see Labour politicians throw out short-term solutions for the sake of headlines – like getting the private sector to mop up the backlog, or letting patients bypass GPs. We need a strategic solution, or there’s every chance that failing public confidence in the NHS turns into a stampede towards private care, paid for out of people’s savings and even borrowing.

Wanless, who died in 2012, understood the big picture. We live in an ageing society, where public health is damaged by poverty and austerity. Those are two big drivers of demand. A third is new technologies: in a free, equal healthcare system, innovation drives demand.

So, he said, because healthcare spending cannot expand infinitely as a proportion of GDP, you have to seek bang for bucks. You need to spend big-time on IT, seek further productivity gains by altering the skill mix, move treatment from hospitals to primary care and engage the whole of society in a drive to improve public health. Wanless was so clear and technocratic in these conclusions that reading them today makes me want to weep.

Because every one of them was thwarted by the marketisation process Labour unleashed alongside the extra money. Under Blair and Brown, money was supposed to “follow the patient”. It didn’t work. Under Cameron, there was supposed to be a full-blown internal market. It collapsed.

Polyclinics – primary care factories to replace GP surgeries – were invented, then scrapped. A digital patient record system consumed £10bn of taxpayers’ money before collapsing in chaos. Every Conservative prime minister of the past 12 years has bottled the challenge of how to pay for elderly social care. And then Brexit switched off the supply of migrant labour that both the NHS and the care system relied on, and a decade of underfunding did the rest.

So what we’re living through is not some contingent crisis, triggered by Covid, inflation and incompetence. It’s long-term and strategic, whereby each aspect of it – skills shortage, obesity, ageing, and scandalous mismanagement of data – fuels the other, because there is no strategic design.

So it’s time to stop shouting “Defend the NHS” – though I do want to defend the principle of taxpayer-funded healthcare at the point of need. We need to transform the NHS, or consent for it will weaken.

Since healthcare is essentially about human-to-human services, the only way you achieve productivity gains is through investment in data and machines, a revolution in workflow, and by reducing demand through improving public health. (Laughably, when the government met the health unions this month it demanded “productivity” increases, from people already working many hours a day for free.)

Real productivity rises demand not just extra money from the taxpayer, but the redistribution of wealth and power.

In what kind of societies does public health improve? Educated, cooperative, solidaristic ones, with high levels of trust in public information. What kind of data processing brings rapid and tangible improvements in preventive medicine? The kind where you don’t hand everything over to predatory Silicon Valley corporations to make megaprofits.

How do you alter the skill mix rationally between GPs, physios, pharmacists and care workers? You stop pitting them against each other through quasi-market mechanisms, and you pay them enough so that people want to do the job. In short, you stop trying to force market principles and norms of behaviour into a system that doesn’t need them.

The NHS needs to become a massive engine of redistribution – not just of wealth, but of wellbeing. Because that’s the dirty secret of 21st-century Britain: the unwellness, stress, morbidity and mental ill-health that has become the norm for many on low incomes, alongside the lifestyle of mindfulness and spinach smoothies that is available to the middle and upper classes.

Putting that right will probably take another 20 years, so ingrained are the long-term problems. So while every good idea is welcome, they’ve got to be part of a strategic transformation.