On one level, it should be obvious enough why Keir Starmer has emphasised that a plan to flatten the rising cost of welfare is not merely about saving money. It is also, he said, a “moral duty”.

Previous cuts to pensioners’ winter fuel allowance and international aid, or the refusal to lift an impoverishing two-child cap on benefits, have been deemed painful-but-necessary choices given the government’s economic inheritance and the growing global disorder.

But slicing out billions of pounds paid to sick and disabled people is fraught with such political difficulty that even the last government only vaguely threatened to do it.

So, just in case you missed the message, Downing Street is keen that welfare reforms are explained less through a Treasury abacus than by the values of a Labour party – “the clue is in the name” – that seeks to give ordinary people the chance to find the “dignity” and “pride” that comes with decent work for decent wages.

The prime minister has described how having a million young people in neither work nor training and education “is a moral issue that cuts across the opportunity and aspiration that are the root of my values… I am not prepared to shrug my shoulders and walk past it.”

Yet too often moral missions for the poor, no matter how well-intentioned, can slide into becoming moral judgments on “the undeserving poor”. People who are unable or sometimes unwilling to seize whatever opportunities allotted to them have, at regular intervals in the history of this country, been dismissed as “feckless,” “idle,” or even “criminal”.

There was a lot of this during the austerity years of the last government when what David Cameron himself called a “moral mission” against benefit fraud was used to justify cutting fully a fifth out of the income of the UK’s poorest families and underpinned by more than a thousand newspaper articles a year about “cheats,” “scams,” “fiddles,” “scroungers,” “spongers” or “skivers”.

Last week it was perhaps inevitable that these sentiments could be found lurking in the comment pages of the Daily Mail. There was Quentin Letts opining that “paying millions of citizens not to work only encourages more to try it on,” before adding primly, “please note that the Bible encourages toil and scorns sloth”.

Elsewhere in the same newspaper, Andrew Neil (who these days spends much of his time writing from his home in the south of France where he once boasted he has a rosé wine bearing his name “specially bottled for me”) described how “a workshy epidemic is a uniquely British phenomenon”. He asked why anyone had thought it was a good idea to give cash benefits “to folk who struggle to handle money” such as “drug and alcohol addicts”.

In fairness, ministers have generally tried to avoid this sort of nonsense. Although Liz Kendall, the work and pensions secretary, suggested that some disability claimants are “taking the mickey”, she has also said: “We are not going to write you off and blame you. We’re going to bust a gut to give you the support you need to build a better life.”

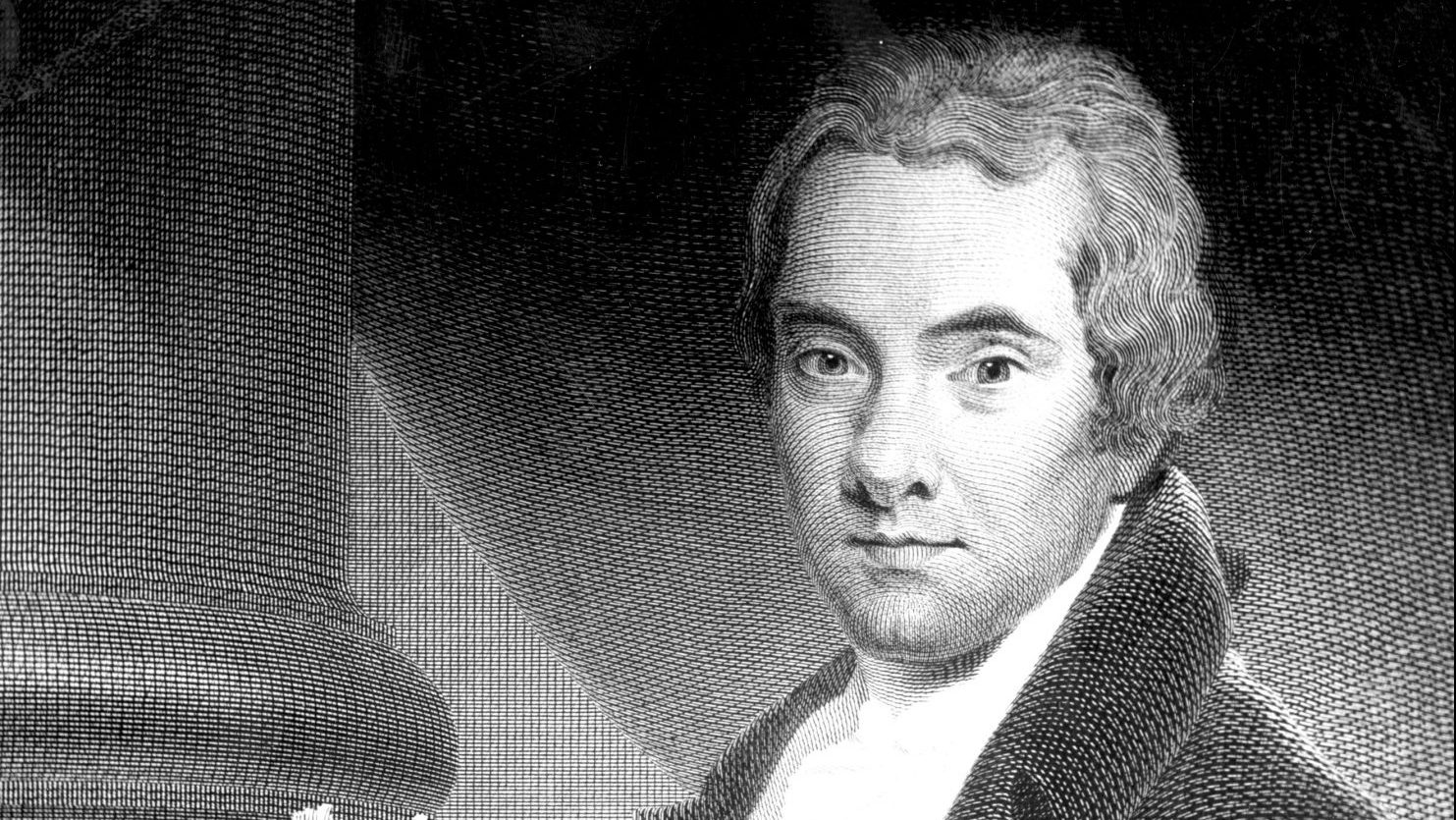

But the notion of “moral mission”, too often tinged with notions of moral superiority, to clean up society is one of the myths that we argue in our book, England, has distorted politics over recent years. A big part of this can be traced back to the religious revival of the late 18th century and the paradoxical story of William Wilberforce. Although rightly venerated for his campaign against a slave trade that he called the “foulest blot on our national character”, he regarded the reformation of “England’s manners” – by which he meant the morals of its working classes – as a matter of equal importance.

An Evangelical Christian and, by most accounts, a kind-hearted man who treated elderly servants, tenants and even animals with a tenderness that belied his time, Wilberforce was also involved in efforts to improve conditions for children who had to sweep chimneys or those he saw on a visit to rural Somerset trapped in an “excess of vice, poverty, and ignorance”.

But he was generally more concerned with spiritual welfare than in the material circumstances of people whether they were unemployed workers in England or former slaves in the Caribbean. Wilberforce helped found the Society for the Suppression of Vice that clocked up 623 prosecutions for breaking Sabbath laws in barely a year before moving on to new targets such as gingerbread fairs and nude bathing.

He said that “inferior classes” should be content that their “more lowly path has been allotted to them by the hand of God” not least because they were spared “the many temptations” afflicting their superiors. Indeed, he took opium three times a day and tried his best to drink “no more than six glasses” of wine a night, even while voting for laws that punished hungry workers going on strike with two months’ hard labour.

The year after Wilberforce died, parliament approved changes to Poor Laws that MPs at the time complained were costing too much money and encouraging an ungodly idleness. The new rules infamously stipulated the poorest had to go into workhouses designed to be so harsh as to deter anyone in their right mind from relying on them.

No one, of course, is seriously comparing that regime to the government’s planned reforms to a creaking welfare system. But, just as it is a mistake to draw exact parallels between today and the worst excesses or hypocrisy of England’s Victorian moral missionaries, it’s also wrong to dismiss all the achievements of their reforming religious zeal.

There is much to admire in the cooperatives and self-help mutual societies that sprang out of Methodist northern England, as well as the parks, libraries, schools and clean water supplies created by temperance campaigners. Together, they represented a thirst for improvement grounded in the lives of the people themselves. It’s a part of the Labour tradition mentioned by Starmer last week, just as the idea of poverty being a symptom of moral weakness belongs to the conservative right.

Most of all, though, it is important not to get carried away by tall tales and headlines. Instead, we need to recognise the complexities of real life. Solutions aren’t going to be found in the simplistic prescriptions of piety, or the knee-jerk prejudices of the Daily Mail. The reasons why Britain now has so many people claiming sickness and disability benefits are as muddled as the country itself.

Sure, some of it has to do with perverse incentives offered by the benefits system and rules that, like any system, will always get tested by people seeking advantage. But other explanations include the ravages of the pandemic, rising pension ages that have left more infirm people outside retirement and an NHS where people spend years waiting for diagnoses, let alone operations or therapy. Nor can it be underestimated how this country has too often and for too many people, become a miserable – and, yes, depressing – place in which to grow up and grow old over the past 15 years.

Ultimately, the success of the welfare reforms will depend not so much on the language used to describe them as on what works. Perhaps the proposed changes will give people the help they need to discover the dignity of work.

But the government’s impact studies, expected to be published shortly, are rumoured to show that tens of thousands more children will end up in poverty as a result. And, if that’s the case, it will be a lot harder for any minister to claim this latest moral mission isn’t just another example of people being punished for being poor.

England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country and How To Set Them Straight, by Tom Baldwin and Marc Stears, is published in paperback this week by Bloomsbury