In 1920 Poland famously saved Europe from being overrun by Lenin’s Red Army. The Bolshevik leader launched his men on an assault on nations west of Russia which he believed were ripe for revolution, helped along by Russian bayonets and machine guns. A hastily formed Polish army was thrown together and, thanks to brilliant generalship, defeated the Bolshevik soldiers at the Battle of the Vistula, the river that runs through Warsaw. But arguably all the Poles did was save Europe for autocracy, for nationalist, anti-Semitic politics, and in due course for fascism and war.

Now, 103 years later, Poland may just have saved Europe from disintegrating into a clutch of petty nationalist regimes, ruled by parties opposed to European values, EU obligations and the rule of law, hostile to judicial independence, press freedom and in some cases hostile to women’s rights and with more than a whiff of anti-Semitism.

Only a few months ago, some commentators were suggesting that the PiS (Law and Justice) party, the hard right Polish party, was as strongly in control of Poland as Viktor Orban’s illiberal, Jew-baiting Fidesz party that rules Hungary.

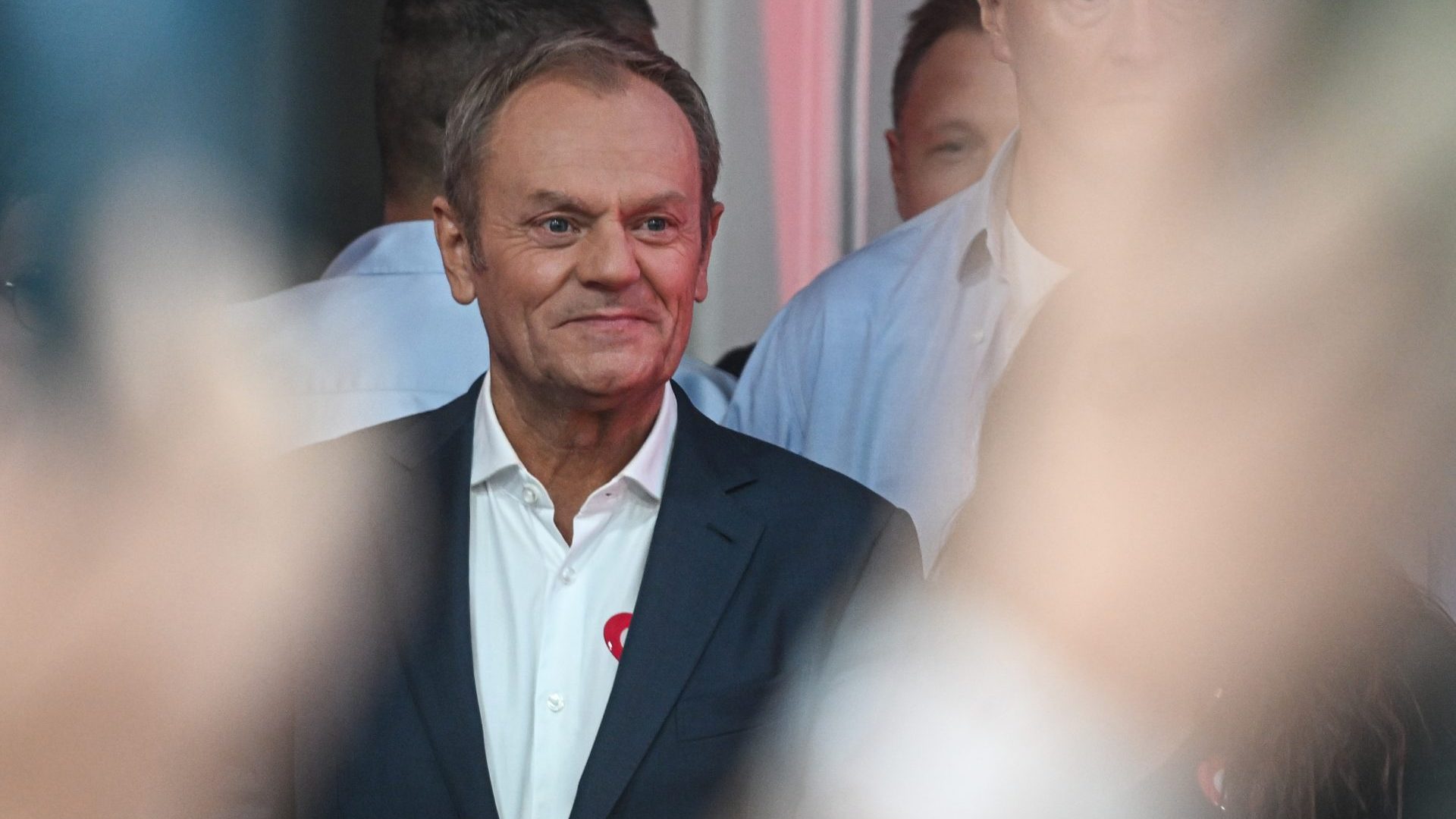

Last Sunday, across Poland, millions of voters queued patiently to vote out PiS and replace the rightist government with three parties: a centre-right liberal party, a social democratic one and a heterogeneous liberal party called “Third Way.”

There are three consequences of this political revolution.

First, Poland, the EU’s fifth biggest and fastest growing economy and now a serious military player, can rejoin the mainstream of European nations, like Germany, France, Spain, or Greece, as a good faith participant in formulating EU policy.

Second, the defeat of PiS exposes still further the isolation of Tory Brexit England. The first Brexit in 2009 was a political one, when David Cameron took the Conservative Party out of the European People’s Party, the centre right federation of EU parties. Cameron hoped that this would calm down the religious hostility of the Tory europhobes.

His fellow centre-right leaders in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and other EU nations were shocked by the move. They began to understand that an all-out anti-European fever had infected the Conservatives. Tory MEPs were suddenly left homeless, having rejected their closest political allies.

But in the European Parliament, MEPs can only function effectively, get on to committees, become members of country groups to travel abroad, get plenary speaking slots if they belong to a political group with parties from more than one nation. So Cameron linked up with the parliamentary group that contained PiS and other far right, extreme parties. Now the defeat of their pro-Brexit ally in Poland further isolates the Tories.

Third, the conventional line in much academic discussion on Europe, especially in English speaking circles in Britain and America, is that Europe is being taken over by the right. This line has both left proponents like Cas Mudde, the Dutch political scientist, and Professor Matthew Goodwin who thinks Europe will soon be taken over by Trump-style national identity politics.

Thankfully their predictions do not seem to be coming true. Earlier this year Spain’s Socialists held off a strong challenge from the hard right. Germany has a social democratic Chancellor and Green foreign minister. France is governed by a liberal prime minister. Rightist politicians like France’s Marine Le Pen or Italy’s Georgia Meloni have dropped their hostility to the EU and re-centred their parties.

The hard right parties come and go, in and out of the mosaic of coalition governments. That seems to be the new normal in European politics since the end of the stable period of monolithic centrist politics that existed between 1950 and 2010.

Poland’s PiS was the flag bearer for this trend, a party that denied judicial independence, media freedom, separation of powers, abortion rights, and brought with it all the squalid prejudices of loud mouthed bar-room rightism. It is now in opposition.

Its defeat does not mean Europe is turning left. The democratic left in Europe has yet to reinvent itself as a 21st century movement. But the resistance of the Poles to the 1930s-style PiS politics of the hard right is welcome news. Next year we will see if a renewed Labour Party can do the same here in Britain, to begin the country’s journey back from the current, disastrous Brexit isolation.